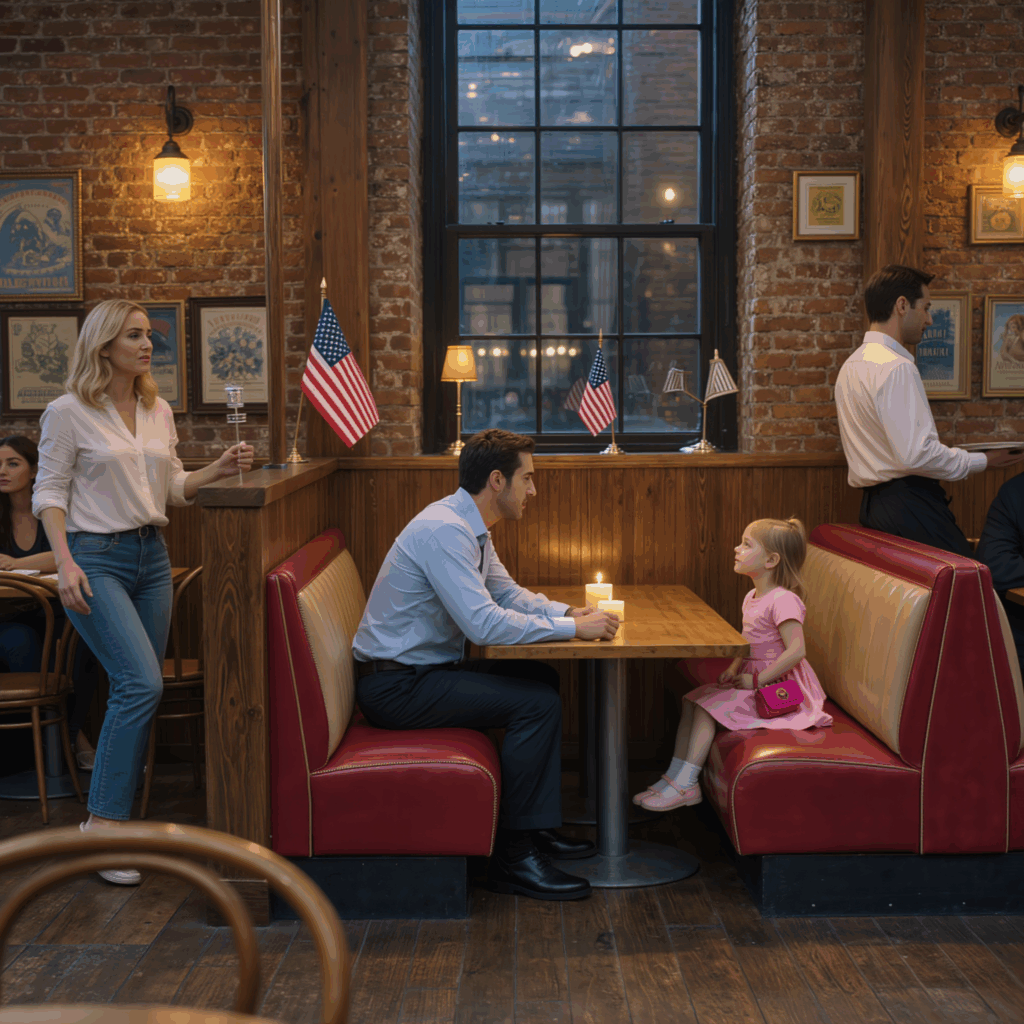

The jazz wasn’t trying to be romantic; it was just doing its job—filling the quiet between clinks of glass and low laughter—yet it kept drifting back to the small, flickering circle of light on Adrian Shaw’s table as if the candle were a spotlight he hadn’t asked for. He checked his watch: 7:22 p.m. Twenty-two minutes late. He’d given the evening a deadline and the deadline had blown right past him like a missed exit on I-5. He signaled for the check. Then a shadow fell across the table—too short to be the waitress—and he looked up into a face that did not belong in any plan he’d made for his life.

“Excuse me,” the little girl said, voice as clear and purpose-built as a bell. “Are you Mr. Adrian?”

He nodded before he could remember the script for adult-to-child conversation. “I am. And you are?”

“I’m Lily,” she said gravely, pink dress, pink ribbon, tiny purse clutched in both hands like a document pouch. “My mommy sent me. She’s very sorry she’s late.”

Everything in him that was scheduled and efficient and willing to write off the night softened. “Your mommy sent you in here to find me?”

“She showed me your picture on her phone,” Lily said with perfect confidence. “She said you’d be by the window with a candle, and here you are.” Then, with the determined precision of a person with a job to do, she scrambled onto the empty chair across from him and folded her hands, ankles swinging. “Mommy says not to talk to strangers,” she added, “but she said you’re her friend.”

Adrian smiled despite himself. “Then I suppose we’re not strangers.”

Lily studied him, as if measuring him against criteria he couldn’t see. “Are you going to marry my mommy?”

He almost choked on the wrong breath. Around them, café conversation blurred into a hush of velvet and glass. He opened his mouth with no words loaded and was saved by a voice at the door—breathless, apologetic, edged in panic.

“Lily! Oh my God—there you are.”

The woman who rushed in had the same sunlight hair as the girl, shaken loose from a bun by the wind and the run. She was beautiful in a way that didn’t seem curated: flushed cheeks, worried eyes, a laugh line she tried to suppress while scolding. She reached their table, hand on Lily’s shoulder, gaze lifted to Adrian with that particular American blend of politeness and self-recrimination.

“I am so, so sorry.” Her eyes flicked to the candle, the menu, the scene she’d interrupted. “She was supposed to wait by the door, and then the meter wouldn’t take my card, and—” She stopped, breathed, squared herself. “I’m Isabel. This is Lily. If you want to leave, I fully understand.”

Lily turned her head, affronted. “But I found him.”

“You did,” Isabel said, smoothing the ribbon, voice softening. “And we will have a conversation about that later.”

Adrian stood halfway out of his chair without deciding to. “Please—sit. It’s fine. Really.” He looked from Lily to Isabel and felt something align in him that didn’t come from spreadsheets or projections. “You sent the best ambassador I’ve ever met.”

Isabel laughed, the apology easing out of her shoulders. She sat. Lily slid to the chair at her side, still composed, still measuring him.

“I should have told you I have a daughter,” Isabel said, not quite looking at him. “Your friend Mark was enthusiastic and I… wanted one evening where I wasn’t being interviewed about childcare before someone knew my last name. That was wrong of me.”

“It was human,” Adrian said. He realized how true it was only as he said it. “And for what it’s worth, Lily has impeccable communication skills.”

“See?” Lily murmured, almost to herself. “Told you.”

They ordered. The waitress, who had watched the whole scene with the soft smile of a person who’s been waiting to see if the evening would go cruel or kind, brought crayons and a kids’ menu that unfolded like a map. As dinners arrived and the candle burned a smaller circle, Adrian drifted into a world he didn’t know how to schedule: pep talks about sharing at daycare; the correct way to cut pancakes (“triangles taste better”); the difference between an owie and an emergency; the names of three stuffed animals who had opinions about bedtime. He listened. He asked. He learned.

Later he would tell friends that the night he fell in love, it happened twice—first with a woman whose laugh made the rest of the room forget itself, and then with a small, serious person who annotated the world with honesty adults can’t afford.

They finished dessert, or rather Lily finished the whipped cream and declared the chocolate “too spicy.” Adrian reached for the bill; Isabel reached too, then stopped.

“You don’t have to—”

“I know,” he said. “I want to.” He slid his card in and only then realized he’d used want rather than should. It startled him—not the cost, but the ease.

Outside, under the neon glow of a coffee cup and the old brick hush of Capitol Hill, the wind carried weekend voices and bus brakes and the faintest smell of rain even though the sky was clear. Lily tugged at Adrian’s sleeve.

“Mr. Adrian?”

“Yes?”

“When we go on the next date, can we get the big pretzel?”

He laughed, helpless. Isabel looked both mortified and relieved that someone had asked the question out loud. “Lily,” she warned gently.

“It’s okay,” Adrian said, and the words were more than about the pretzel. “It’s very okay.”

—

A week later, they didn’t go for pretzels; they went for pancakes. The diner on the corner of Pine and Thirteenth was the kind of small American place that collects stories the way other places collect tips. A waitress named Donna called everyone honey and had a tattoo of a sparrow you only noticed when she reached for the coffeepot. Lily slid into the booth like she owned it. Isabel shrugged off her coat, still careful, still watching him for discomfort like a person who’s learned to anticipate the moment when men stand up with a polite excuse and a swish of cologne.

Adrian made space for the crayons and the syrup and whatever unknown test he might be in. He learned to cut triangles. He passed the butter at the right moment. He did not check his email.

There was history, of course. There always is. It came out in pieces, like a map unrolled slower than the impatient eye wants.

Isabel had moved to Seattle from Boise at twenty-two with a scholarship, an old Corolla, and the kind of ambition that feels like you’re going to outrun your past by force of will. She’d met Ethan at a music venue in Fremont where the band was too loud and the drinks were too expensive. He had work boots and shoulders that made you feel like you could lean and not fall, and he had a laugh that promised rest. He also had a carefully hidden taste for the edge and a talent for vanishing. By the time she realized that the promises weren’t all true, the test had two lines. She didn’t marry him. He didn’t stay. When Lily arrived, love did too—vast, corrective, demanding—along with a math of money and time that did not add up without mercy.

Ethan mailed a birthday card once. He Venmo’d $50 another time with the note “for the kid.” He texted a few times from new numbers with new promises. Then nothing.

“I learned to be efficient,” Isabel said, stirring coffee she didn’t need. “You have to. There’s no such thing as later with a four-year-old.”

Adrian listened. He didn’t make vows he couldn’t keep. He didn’t try to erase the past with the future he imagined. He drove them home, slow, careful, learning the rhythm of school pick-ups, naps, the art of leaving the party while everyone is still having a good time.

Mark, his business partner, watched this evolution with a mixture of delighted teasing and cautious CFO-brain.

“You’re soft,” Mark said, in the way only a friend can say without drawing blood. “You’re saying no to meetings.”

“I’m saying yes to other things,” Adrian said. He surprised himself with how little defense he needed. “There’s a human being who asks me why the moon follows the car and genuinely wants an answer. That matters.”

Mark raised his hands. “I’m not arguing with the moon.”

They closed a deal that quarter that should have tasted like victory and instead tasted like relief. Adrian had spent a decade building Shaw & Pierce, a consultancy with a little more humanity than its website allowed. He was good at it. He could see around corners, anticipate where a model was thin or a team was lying to itself. He could sit in a boardroom and translate boredom into action without raising his voice. He had given the best of himself to numbers and strategies and the polite war of negotiation. Now he learned to give the best of himself to bedtime stories.

—

If this were the movie version, the trouble would arrive wearing a black hat. In life, trouble shows up more casually.

It began with the neighbor. Every building has one—the person who takes the HOA by the throat and decides to squeeze. Mrs. Henderson was not cruel so much as she was scared of change, which, metabolized incorrectly, looks identical. She liked quiet hallways and predictable parking spaces and the unspoken rule that children should be as invisible as furniture.

Lily, who saw the world as a place worth talking to, failed that test without knowing one existed. She greeted Mrs. Henderson every morning with cheerful reports about weather and the school hamster. Mrs. Henderson nodded briskly and, when Lily and Isabel were out of earshot, wrote emails about noise.

Then Isabel slipped one Tuesday on the concrete step that had cracked all winter and never been repaired. She didn’t spill the groceries. She did bruise her knee. Lily gasped and kissed the bruise, then laughed, because children know the difference between hurt and harm. Mrs. Henderson, arriving with a package on her hip and righteous exhaustion in her eyes, saw a narrative she preferred.

By Thursday, an anonymous tip had arrived at Child Protective Services describing a single mother “leaving her child unattended” and a “parade of male visitors” and “concerning activity late at night.” It was not true, but truth has to work harder than rumor.

The knock came at 6:42 p.m., spaghetti on the stove, crayons on the table, Adrian reading a library book in a voice that made Lily giggle. The caseworker, Sandra, was competent, kind in the way that matters, and practiced enough to see a kitchen that smelled like dinner and a child who reached for her mother’s hand without flinching. She asked questions. She looked in the refrigerator. She checked the smoke alarm. She observed. Her brow furrowed when Isabel’s body curved unconsciously in front of Lily the way some women learn to be shields without ever being taught.

“I’m sorry,” Sandra said on her way out, hand on the doorknob. “This seems like a neighbor who’s… anxious. I’ll file this as unsubstantiated and close it.”

Isabel nodded, trying to smile, but once the door latched, something in her shook. It wasn’t scandal or shame; it was the old tremor that comes when you remember the world can take things from you just because it can.

Adrian put the pot on simmer, turned off the audiobook dragon, folded her into him. Lily, reading the room with the clarity of a child who knows when the adults need to be reassured, took both their hands and placed them together like she was making a new shape.

“We’re okay,” Lily declared. “We’re a triangle.”

“Triangles are strong,” Adrian said, voice steady. “We learned that about pancakes.”

They ate dinner. The sauce burned a little. They laughed anyway. Adrian washed dishes while Isabel dried. That’s when another knock came, a different rhythm, the sound of a past returning without invitation.

Ethan stood in the hall with a bouquet already wilting and a smile that had been charming when Isabel was twenty-two and had since become a brand. He looked good. That’s the worst part; sometimes the villains lift weights. He glanced at Adrian, filed him into a category he would mock later, and aimed his attention at the child.

“Hey, Jellybean,” he said, the old nickname tasting sour in Isabel’s mouth. “Daddy’s back.”

Lily’s eyes narrowed because children are born with a radar and adults spend the rest of their lives interfering with it. She looked up at her mother, then at Adrian.

“You’re late,” she said to Ethan, not unkindly. “We already had dinner.”

Ethan laughed like the room had made a joke. “I got a little tied up, kiddo. But I’m here now.”

“Why?” Lily asked.

It was an excellent question. The answer, which would unspool over the next months, was a combination of money, regret used as currency, and a new girlfriend with strong opinions about what “real men” do. He had an attorney. He had a plan that included Instagram photos with captions about family and redemption. He had learned a vocabulary that sounded like responsibility but mostly meant control.

He wanted custody, he said. Or at least partial custody. Maybe just every other weekend. We can be reasonable, he said, smiling like they were co-conspirators. He had not paid child support; he had missed first words, first fevers, first days of preschool; he had not earned the right to any of this. But the law, written to be fair, sometimes struggles to account for the difference between blood and devotion.

Isabel did not slam the door because that’s not who she was. She invited him to sit. He did, like a king entertaining a petition. He talked about fathers’ rights. He talked about stability, as if his life were not a series of sudden decisions with no forwarding address. Lily excused herself to the floor with her crayons and drew a triangle with three smiling faces and, on the edges, lines that looked like beams.

Adrian listened. His chest felt like someone had poured cold water into it. He had no legal standing. He had only what he could control: calm, clarity, kindness in the face of noise. He poured coffee he didn’t want and sat at a table where justice and the law were cousins who didn’t always speak.

After Ethan left—with a hug Lily sidestepped and a promise to “be in touch”—Isabel sank into the chair he’d warmed. She looked at Adrian like a person who has spent too much of her life being brave.

“I can fight,” she said, voice steady, as if proving it, “and I will. But I—”

“You won’t do it alone,” Adrian said. He didn’t raise his voice to make it sound like a vow. He didn’t need to.

—

The fight looked the way American fights do when the subject is a child: filings and affidavits and case numbers like serial codes; mediation sessions where a stranger with a calendar tries to carve a human life into alternating weekends and Wednesday dinners; phone logs; character references. Isabel’s attorney, a woman named Priya with a braid like a sword and a kindness that never confused itself with accommodation, prepared her like she would a witness in the kind of case that cleaves a life into before and after.

“He will try to make this about his rights,” Priya said, markers squeaking on a whiteboard. “We will make it about Lily’s stability. He will talk about biology. We will talk about bedtime. He will say he has changed. We will not argue with his adjectives; we will present evidence. Stay boring, Ms. Morales. Boring wins.”

Adrian learned the brittle etiquette of proximity to a custody case. He learned when to speak and when not to. He learned to say, without apology, “I love her,” and to understand that love, while the most important fact in his body, was not the most relevant fact in the court.

There were righteous moments. There were also humiliations that only people who have ever sat under fluorescent lights while strangers discuss your fitness to care for a person you would step into traffic for can understand. There was a home visit from a guardian ad litem who spoke gently to Lily about routines. There was a deposition where Ethan’s attorney, slick and smiling, asked Isabel if she had ever left Lily alone “for any period of time.” There were emails from Ethan time-stamped at 2:12 a.m. with subject lines like “Right of First Refusal” that landed like grenades in a peaceful kitchen.

The neighbor, Mrs. Henderson, submitted a letter about “men coming and going at all hours,” which Priya demolished with building security logs that showed precisely one man entering that apartment regularly: Adrian, whose name was on the visitor list with times that matched bath-books-bed. Sandra, the caseworker, filed her own report from the earlier visit: unfounded, unsubstantiated, home safe, child bonded with mother, presence of supportive adult male companion who exhibits appropriate boundaries. If justice is the slow accumulation of facts until cruelty has nothing left to hold on to, then justice was working, grain by grain.

It still hurt. It hurt in the daily way—the way things that should be simple become hard when someone who has forfeited moral standing insists on legal standing because the law must pretend not to know what it knows.

There were moments of grace. One of them happened on a morning in October when the city smelled like wet leaves and cold coffee. Adrian took Lily to school, hand in hand, backpack bouncing. She stopped at the gate and looked up at him.

“Mr. Adrian?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“When you come to pick me up, will you be my family then too?”

He swallowed the lump that arrived without permission. “I am your family all the time,” he said. “Even when I’m not in the room.”

She considered this like a scientist. “Okay,” she said finally. “I’ll tell Ms. Kate that.”

“Tell Ms. Kate what?”

“That my family is triangles,” Lily said, already turning toward the playground. “Triangles are stronger than squares because squares can fall over.”

He didn’t know if that was true in geometry. He knew it was true in his chest.

—

News

She Swore She’d Escape Christmas Again—Until a Small-Town Night, One American Flag Above a Donation Jar, and a Stranger’s Eyes Made Her Stop Running Long Enough to Choose Something Dangerous: The Truth.

She Hated Christmas… Until She Met HIM | Small Town, Big Magic And Real Feelings (Expanded ~6000 Words, Clean Copy)…

My Son Sold My Late Husband’s Classic Car To Take His Wife To Paris—And The Dealership Owner Called Me The Next Morning. – Sam

My son sold my late husband’s classic car to take his wife to Paris. The dealership owner called me the…

P2-My daughter abandoned her autistic son at my front door in the United States and never came back. Eleven years later, that boy—my grandson—built a $3.2M verification app, and the doorbell rang again with a lawyer and a smile that never reached her eyes.

That future started taking shape the summer Ethan turned twelve. He’d been scanning documents for months, organizing everything into his…

P1-My daughter abandoned her autistic son at my front door in the United States and never came back. Eleven years later, that boy—my grandson—built a $3.2M verification app, and the doorbell rang again with a lawyer and a smile that never reached her eyes.

My daughter left her five‑year‑old autistic son at my door and never came back. That was eleven years ago. I…

Sister texted, “You’re not invited to the wedding. Goodbye, LOSER.” My mom added a heart emoji. – Sam

Sister texted, “You’re not invited to the wedding. Goodbye, loser.” My mom added a heart emoji. I replied, “Perfect. Then…

P2-“Pay $100,000 Or We Postpone” — He Thought I Was A Small Branch Manager. He Never Checked Who Holds His Family’s $4.2M Note

Monday morning at nine, the Sheriff’s Department posted the notice the way the law asks. A local station ran a…

End of content

No more pages to load