What do you mean you don’t have the keys? The house is empty. That can’t be right, I said, my knuckles white around the phone as if I could wring a better answer out of static. The neighbor across the street—Mr. Caldwell, khaki shorts, a sun-faded ball cap—stood on his porch, arms folded, watching me pace the sidewalk in front of what used to be my home.

My name is Jasmine Rojas, and I had just driven four hours from my university to Bakersfield for spring break, only to find a real estate sign hammered into the front lawn. It was a crisp sign with the agent’s smiling headshot and a phone number I didn’t recognize. The windows were bare—no curtains, no blinds, just sun rectangles on empty floors. Three black garbage bags slumped on the porch like unwanted guests. When I loosened one’s knot and peeked inside, I saw my clothes and dog-eared paperbacks, fragments of a life I’d put on pause when I went to college.

“Your father said you should have called first,” my uncle Thomas said when he picked up, his voice careful like he was stepping around a sinkhole. “They moved last week. Didn’t they tell you?”

“No,” I said, the word catching on the lump in my throat. “They didn’t tell me anything.”

I hung up and called my father. The phone rang and rang. Each ring felt like a drip in a slow leak you know will flood everything eventually. “Hello?” he answered at last, his voice flat.

“Dad, the house is empty. There are garbage bags with my stuff on the porch. What’s going on?”

A pause. Then: “We moved. You’re an adult now. Deal with it.”

The line went dead.

I stared at my phone as if it had bitten me. I called back—voicemail. I tried my mother—voicemail. My younger brother, Gabriel—no answer. Just like that, a trapdoor opened under the floorboards of my life.

I stood there until the sun lowered and the maple tree my father and I had planted when I was eight stretched its long fingers across the yard. The tree still stood. The house didn’t belong to us anymore.

I didn’t cry. Not then. I knotted the garbage bags and loaded them into my trunk. I took the agent’s flyer from the sign out of some petty impulse I couldn’t name and checked into a motel off the highway. The room smelled like lemon cleaner and yesterday’s cigarettes. I spread my salvaged possessions across the scratchy bedspread: a winter coat I’d outgrown but refused to part with, a stack of textbooks with my notes marching in the margins, a cracked picture frame with a photo from the beach three summers ago—everyone smiling. Everyone, apparently, a liar.

That night, I made a decision. If they wanted to erase me, I would return the favor. I would cut all ties and build something they could never take away. If family was supposed to be unconditional, mine had stapled a thick set of conditions across the front.

I grew up on dinner-table sermons about sacrifice. “We came here with nothing so you could have everything,” my father would say, palms up like an offering. “Education is your ticket.”

I took that seriously. While other kids raided closets for parties, I raided the library for practice exams. When my friends picked up summer jobs at the mall, I interned at the courthouse, watching a judge with silver hair and a voice like a gavel keep a tight grip on a crowded docket. I kept a 3.9 in pre-law while working part-time at the campus tutoring center. I sent part of my scholarship deposit home every month because that’s what you did when your parents said they were stretched thin.

Gabriel was different. He could be sweet, but school sandpapered him. He preferred video games and late mornings and once tried to shoplift a wireless headset because he said he needed to hear himself better. My parents defended him, forgave him, insisted he was “finding his way.” Somehow I had been the one they left behind.

I woke before dawn in the motel. Bakersfield traffic had a way of sounding like an ocean if you listened long enough. I sat on the bed and stared at my picture frame until the glass caught the sunrise. Then I called the one person I trusted to tell me the truth even if it hurt.

“Jasmine?” Professor Margaret Wilkins answered on the first ring. Her voice was warm, professorly. “Is everything alright?”

“They moved,” I said. “I came home to a realtor sign and my clothes in trash bags.”

Silence, then a soft exhale. “They just left?”

“Yes.”

“Come stay here until the dorms reopen,” she said without hesitation. “No time limit.”

Professor Wilkins lived in a Victorian house not far from campus—a stack of books in every room, two elderly cats named Holmes and Watson, sunlight pooled on hardwood floors. She handed me a key over a mug of tea and the smallest of speeches. “You’ll finish the semester. You’ll finish strong. We’ll figure the rest out together.”

I believed her because she never made promises she couldn’t keep.

Spring break became a blur of reading, writing, and distracting labor. Professor Wilkins had connected me with a summer internship at Riverton Law Partners, a firm known for housing discrimination work. The irony wasn’t lost on either of us. “Channel it,” she said, sliding a stack of case summaries toward me. “The best advocacy grows from lived experience.”

I blocked my family’s numbers that night. My father, my mother, Gabriel, and the handful of aunts and uncles who had always served as the family telegraph. If anyone asked about my family after that, I said, “We’re not in touch,” and let the silence do the rest. Sentimentality, I decided, had no place in the foundation I was pouring.

Riverton’s offices were three floors above a bakery that piped cinnamon into the hallway every morning. The firm’s name was etched on frosted glass in letters too restrained to be self-important. My supervisor, Eleanor Grayson, was an attorney with a quick, deliberate way of speaking, like she was always walking the shortest distance between two facts.

“You have something rare,” she told me after I calmed a young mother who’d been served an eviction notice without cause. “You listen. Most people don’t.”

By the second week, I was handling intake interviews with a paralegal sitting in. Students pushed out of basement apartments by landlords who “suddenly realized” they needed the space for their cousin. Elderly tenants with decades of rent receipts whose landlord had developed a sudden appetite for “market rate.” A line cook whose building started shutting off water on Saturdays to force residents out.

One evening, after a day of three near-identical notices from the same apartment complex, I stayed late collating statements and police incident numbers into a spreadsheet that matched the rhythm of my fury. Eleanor appeared in my doorway at nine, jacket over her arm.

“Burning the midnight oil?” she asked.

“These families have nowhere to go,” I said, highlighted rows glowing on my screen. “The developer is offering two weeks in a motel as compensation for breaking leases early.”

“That’s more than the law requires in most cases,” she said, leaning on the doorframe.

“I know. It’s still wrong. Two weeks isn’t enough to find new housing, let alone pay deposits.”

“The system is a machine trained to favor property,” Eleanor said. “But machines can be hacked. What are you going to do about it?”

The question followed me home like a song I couldn’t stop humming. What could a second-year pre-law student actually do besides sharpen pencils and anger?

The answer arrived sideways at a mandatory financial aid seminar. A speaker from the university’s social innovation office mentioned small grants for student-led projects addressing community needs. Applications were due in two weeks. I left with a pamphlet and a throb in my chest.

That night I wrote a proposal for a student-and-family housing advocacy program—part education, part emergency response, part legal triage. I called it the Safe Space Initiative because the words mattered. I wrote until the screen blurred, then woke and wrote again. Eleanor vetted the legal framing. Professor Wilkins wielded her red pen on my narrative until it hummed.

While I waited, the phone calls began. Six months after they left me on a porch draped with trash bags, my father’s voice showed up as a voicemail. “Jasmine, your mother is worried about you. Call us.” No apology. No address. Just an order disguised as concern.

I didn’t call.

Three days later another message: “This silent treatment is childish, Jasmine. We’re your family.” I saved it. I did not respond. Their calls piled up like unopened bills. They alternated between demands and pleas. None mentioned the moment they turned my life into a curbside pickup.

When the university awarded the grant—twenty-five thousand dollars to launch Safe Space—I celebrated with Professor Wilkins and Eleanor over tacos at a place with tin ceilings and lime-scented napkins. I didn’t tell my parents. When Riverton offered me a paid position to keep the program running through the academic year, I said yes and bought a plant for the office—a stubborn pothos that thrived in bad light.

By January, Safe Space had helped twenty-three students fight wrongful evictions. We converted a storage room at Riverton into an office: a mismatched desk, two secondhand chairs, a whiteboard that became a to-do list the length of a semester. Two volunteer paralegals and a rotating cadre of law students traded shifts. Most days I sprinted from class to the office, ate dinner from a vending machine, reviewed cases until my eyes felt sanded.

The work braided exhaustion and purpose into a rope sturdy enough to pull me through the days. Each family that kept housing, each student who didn’t use their car as a closet, felt like a personal reprieve. I was building something from the wreckage. Something mine.

My parents increased their campaign as if volume could substitute for contrition. The voicemails grew more elaborate, minor updates delivered like we were mid-conversation: “Gabriel got into community college.” “The neighbors brought tamales, not as good as your mother’s.” I could hear pots clinking in the background sometimes and had to set the phone down until the ache retreated.

On a Tuesday in February, I was coaching a sophomore named Devon whose landlord had rented his room to someone else during winter break despite a paid-up lease. The office phone rang. “Safe Space Initiative, this is Jasmine.”

“Jasmine, is that you?” my mother asked. Her voice reached through the line and dropped me into another time. “Why haven’t you returned our calls? We’ve been worried sick.”

“Devon, give me a minute?” I covered the mouthpiece. He nodded and stepped into the hall.

“How did you get this number?” I asked, keeping my voice as neutral as a receptionist.

“It’s on your website.” A pause. “We’re your parents. We have the right.”

“You lost that right,” I said, even and quiet. “When you put my belongings in garbage bags and sold our house without telling me. Don’t call this number again.”

“Your father made a mistake,” she said quickly. “We had financial troubles. The house was being foreclosed. We were embarrassed.”

Foreclosure. The word hit a bruise I hadn’t known I had. “If you were in trouble, you could have told me,” I said. “I was already sending money home.”

“Your father wouldn’t allow it,” she said. “His pride. You know how he is.”

I did know. Pride had been the unseen furniture in our house, the thing you learned to walk around without bumping your shin. But pride didn’t explain the trash bags, the silence, the absence of a forwarding address.

“I need to get back to work,” I said. “Please respect my boundaries.” I hung up and placed the receiver down carefully like it might explode. My hands trembled anyway.

Eleanor found me an hour later still staring at the call log like it could decode my life. “You okay?” she asked, perching on the corner of my desk.

I told her what my mother had said about foreclosure.

“People rarely act from pure cruelty,” Eleanor said. “But reasons aren’t the same as excuses. Whatever their trouble, they chose abandonment. That’s a fact.”

I nodded. Her words settled like ballast. And yet a thread of doubt tugged—what if there was more?

The next day, against my better judgment, I searched my family’s names online. I found a cheerful Facebook photo of my mother, my father, and Gabriel in front of a new house posted three weeks after they moved. “New beginnings. So blessed,” the caption read. No evidence of a crisis. No sign of foreclosure. Just a decision and a smile.

The unanswered calls accumulated like dirty snow—ugly and hardening. One hundred twenty. One hundred fifty. Two hundred. I stopped counting when counting felt like participation.

Meanwhile, Safe Space drew more attention. A local news station filmed a segment about our work. Two students cried on camera and hugged me afterward in the parking lot, embarrassed and relieved. The university newspaper ran a profile that made me sound braver than I felt. Case intake doubled. We needed more bodies and more space and more hours than the day had to give.

“I might have a solution,” Eleanor said one afternoon, flipping her laptop toward me. “The Watkins Foundation is accepting proposals. Big money. Real infrastructure.”

The application required every part of me: narrative, budgets, timelines, data. I built a spreadsheet that sang when you scrolled. I gathered letters from clients and quotes from professors and a quiet statement from a judge who had watched a lot of good intentions crash on procedural rocks. The finished proposal was forty-seven pages. I sent it and forced myself not to check my email every four minutes.

Two days later, my phone lit up with a call from a Bakersfield number. “Hello?”

“Jasmine, it’s Mrs. Rita Hernandez from next door,” our old neighbor said, the one who used to slip mangos into our mailbox in summer. “I hope I’m not overstepping, mija. Your brother gave me your number. He said you might not answer if you saw your parents’ names.”

“If this is about reconnecting—”

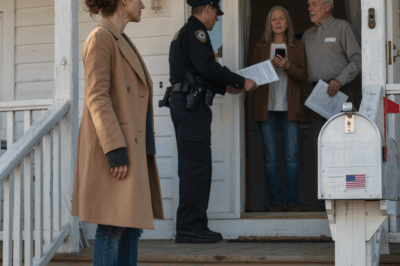

“No,” she said quickly. “It’s… there was a break-in at the old house last night. The agent asked me to keep an eye out. The police were here. The intruder left an envelope with your name on it. The cops gave it to me since I’m the neighbor.”

“An envelope?” My heart spiked. “From who?”

“A law firm. In Mexico. It looks official.”

No one should be sending legal mail to an address I no longer owned. I had updated everything months ago. “Can you open it and read it to me?” I asked.

Papers rustled. “It’s about your grandmother’s estate,” Mrs. Hernandez said carefully. “Your mother’s mother. It says you’ve inherited property in Oaxaca. And there’s a bank statement. Jasmine, it shows a balance over four hundred thousand dollars.”

I sank into my chair. “That can’t be right. My grandmother lived very simply.”

“The letter says the property was developed after her death. Resort condominiums. Your portion is from the sale of two units.”

“Does it say when the inheritance was finalized?”

More paper. “Last March.”

Last March. One month before my parents vacated my life. The timing wasn’t a coincidence. It was a blueprint. They had known. They had kept it.

The Watkins Foundation emailed while I was still absorbing the inheritance bombshell: Safe Space was a finalist. They wanted me and Eleanor to present to their board in person. Under different circumstances, I would have danced in the hallway. Instead, I organized my fear into a task list and made an appointment with the law firm in Oaxaca by phone.

The firm confirmed what the letter said. The inheritance was real. The money was mine. Notification had been sent to my parents as my legal guardians when I was nineteen. The letter sat like a stone in my gut.

“They knew,” I told Professor Wilkins at dinner. “They knew I had an inheritance coming and still put my life in trash bags.”

“Have you considered why?” she asked gently, spearing a green bean and not looking at me as if that might make it easier to answer.

“Money,” I said. “They thought they deserved it.”

“Maybe,” she conceded. “Or maybe they planned to introduce the idea on their terms and make you beholden.”

I pushed my plate away. “Or maybe they never planned to tell me at all.”

The funds hit my account three days before the Watkins presentation. I hadn’t decided what to do with the money, but its presence changed the temperature of the air. For the first time since the lawn sign and the slumping bags, I felt like no one could pull a rug from under me without my permission.

The foundation’s glass building rose out of downtown like an apology for all the places where money made messes and then looked away. The lobby smelled like eucalyptus and copier ink. Eleanor met me in the atrium, immaculate in charcoal, every line of her suit a confidence I could borrow.

“Ready?” she asked.

“As I’ll ever be,” I said, palms damp, throat steady.

We were ushered into a boardroom where eight people sat around a table that could have doubled as a runway. William Watkins, silver hair, black glasses, shook our hands. “We were impressed by your proposal,” he said. “Show us why Safe Space deserves our support.”

I connected my laptop to the projector and began. I talked about our origin story without weight we couldn’t carry. I showed numbers because feelings alone don’t win budgets. I told stories because numbers alone don’t save anyone. Eleanor threaded in context, the legal spine to my narrative heart. They asked hard questions about sustainability and scope and not becoming a landlord’s complaint line. We had answers.

Twenty minutes in, the boardroom door opened. An assistant murmured to Mr. Watkins, who nodded and glanced at me. “Apologies for the interruption,” he said. “Ms. Rojas, there are people here claiming to be your family. They say it’s urgent.”

My mouth went dry. Of course. They had tracked me through the newspaper profile, through whatever network of cousins always know where you are. Eleanor’s hand found my forearm under the table—steady, unhurried.

“Please tell them I’ll speak with them after the presentation,” I said. My voice surprised me by behaving.

Mr. Watkins inclined his head and the assistant disappeared. I resumed. My pulse, previously an orderly drumbeat, became a soloist. I answered the next five questions on muscle memory and will.

When at last they thanked us and said they’d be in touch within two weeks, I felt oddly empty, like someone had scooped me out and set me back down.

“You were excellent,” Eleanor said as we unplugged cables. “Especially under those circumstances.”

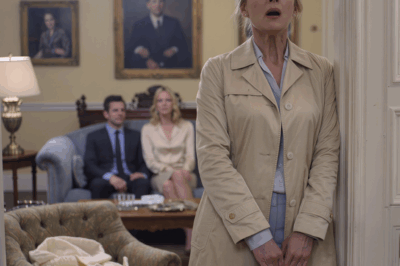

Outside the boardroom, my parents and Gabriel stood in the reception area under a commissioned painting of a river running toward a horizon it could not yet see. My mother rose when she saw me. She looked smaller than I remembered, gray threads catching in her dark hair. My father remained seated, expression guarded like a chess player who sees both victory and loss on the board. Gabriel had grown taller, his stance uncertain in clothes that made him look like he was trying on adulthood.

“Jasmine,” my mother said. “We need to talk.”

Eleanor squeezed my shoulder. “I’ll give you privacy,” she murmured, then drifted away.

“Why are you here?” I asked. “How did you find me?”

“We saw the newspaper article,” my mother said. “It mentioned the presentation.” She reached for my hand, then thought better. “We’ve been trying to reach you for months.”

“I’m aware. Two hundred forty-seven calls is hard to miss.”

“This has gone on long enough,” my father said, rising. “You’re being childish.”

A laugh escaped me, quick and sharp. “Childish is coming home to find your life on a porch.”

“We made a mistake,” my mother said. “We want to make it right.”

“Now?” I asked. “After I rebuilt my life without you? Why now?”

Gabriel shifted. “Just hear them out, Jazz.”

“I know about the inheritance,” I said. “Is that why?”

My father’s face darkened. “You’ve always been quick to judge.”

“And you’ve always been quick to discard,” I said. “You knew about Grandma’s estate last March. You kept it from me. Then you left me behind.”

My mother’s eyes widened. “You know?”

“I know everything that matters.” I glanced at the receptionist, at the assistant pretending not to listen, at the donors’ names etched on glass like commandments. “This isn’t the place.”

We relocated to a coffee shop around the corner. I picked a table near the window and sat across from them where my body could believe in an exit.

“We were ashamed,” my mother said, cupping her paper cup. “We were in trouble. Your father lost hours. We were late on the mortgage. We thought foreclosure was coming.”

“So you left me?” I asked. “You sold the house and put my life in trash bags?”

“We found out about the inheritance right after you went back for spring semester,” my father said. “The lawyers said it would be yours at twenty-one. We thought if we moved and started over, we could fix things before you found out.”

“By erasing me.”

“We panicked,” my mother said. “We thought you’d be better off without our mess. You had your scholarship and your campus. We told ourselves we were sparing you.”

“Now?” I asked. “Why the performance of reconciliation?”

They glanced at each other. Gabriel cleared his throat. “They know they messed up. And the things you’re doing—Safe Space—it’s… I’m proud of you,” he said softly, surprising me.

My father swallowed. “We saw the article. We realized we’d lost something precious.”

“Your successful daughter,” I said.

“Our family,” my mother insisted. Tears hovered, not falling.

I studied their faces like exhibits. My mother’s hands were the same—callused, competent. My father’s shoulders sagged where certainty used to keep them square. I remembered the maple sapling in a hole we dug together and wondered when he stopped believing I was worth watering.

“I’ve built a new life,” I said finally. “New connections. People who value me outside of what I can provide.”

“We’re still your family,” my father said, stubborn as if he could make it true with volume.

“Family doesn’t take your future and hide it,” I said. “Family doesn’t put your belongings in garbage bags.” I set cash on the table for all our coffees and stood. “If you want to make amends, start by respecting my boundaries. Don’t call my workplace. Don’t show up at my presentations. Don’t call me until you can name what you did without blaming embarrassment or pride.”

I left them blinking in the bright afternoon. Outside, the city sounded like it was promising something and I was finally in a position to ask for specifics.

The next morning the Watkins Foundation called. Safe Space had been awarded the full grant—three hundred thousand dollars over three years—plus an additional fifty thousand for operations. I stood very still while the words hung in the air, then sat down and cried in Professor Wilkins’s kitchen where Holmes and Watson circled my ankles and pretended not to notice.

A week later, a national news program did a segment on innovative approaches to housing justice and put our little operation on TV. The calls and emails—good ones—rolled in. A credit union offered pro bono financial workshops for our clients. A church with more rooms than congregants offered meeting space on weeknights. A developer who didn’t hate people sent us a check without asking for a photo op.

My parents never called again.

Safe Space moved out of the storage room and into a small office with a window that made afternoon feel less like surrender. We bought chairs that matched and a coffee maker that whirred like industry. Our intake hotline rang with stories that sounded familiar and very specific, the way pain always is.

On a Thursday in June, a student named Lila came in with a crumpled eviction notice because her landlord wanted to renovate and charge more, and his renovation plan apparently included a wrecking ball to her lease. She held the notice like it might bite. I walked her through her rights and watched her spine sit up under the weight of understanding. When she left, she hugged me in the awkward way of people who didn’t plan to, and I accepted it because maybe we both needed proof that standing your ground was a muscle you could strengthen.

Later that week, I sat in our conference nook with Eleanor and our new program coordinator, a tireless alum named Marcus who’d grown up in public housing and moved like someone who had learned to carry a lot.

“We should open office hours on Saturdays,” Marcus said. “People who work doubles can’t get here on weekdays.”

I thought of my father’s shifts and my mother’s cleaning contracts. “Do it,” I said. “I’ll take the first ones.”

At home that night—home being a tidy two-bedroom apartment I rented month-to-month with a view of a parking lot that sparkled after rain—I sat with the inheritance letter again. Four hundred and eight thousand dollars stared back like a dare. The money didn’t erase what had happened. It didn’t rewrite trash bags into tissue paper or a signpost into a welcome mat. But it was a tool.

I met with a financial advisor who talked to me like a student and not a mark. We built a plan that split the money between a cushion I could sleep on and a fund earmarked for Safe Space’s legal defense pool. The day I signed the paperwork, I felt a thread I hadn’t realized was connecting me to my parents loosen. Money had been our house’s dialect. Silence had been its grammar. I was learning a new language.

When summer surrendered to fall and freshmen tugged rolling suitcases across campus like promises, I began teaching a weekly workshop on tenants’ rights. Students came for the information and stayed for the feeling that they were allowed to know how power worked and how to pry open a window when a door locked. Sometimes they asked me about my family. I told them the truth that fit in a sentence: “We’re not in touch.” Sometimes I told them more: “The family you build can be stronger than the one you’re born into.”

On the anniversary of the day I found the sign in our lawn, I drove back to Bakersfield. No noble reason. I wanted to see. The house looked smaller, as houses do after you grow. The new owners had painted the door a cheerful red and replaced the dying shrubs with native grasses that swallowed the breeze and gave it back. The maple tree stood taller, leaves flashing green like they had something to say.

I parked across the street and watched a kid pedal down the sidewalk in a helmet that took his head from human to astronaut. Mr. Caldwell, the neighbor who’d watched me pace a year earlier, lifted a hand. I lifted mine.

“Looks good, doesn’t it?” he called.

“It does,” I said, and meant it. The house had a life. I had a life. They did not need to be the same.

I didn’t stay long. I drove to Mrs. Hernandez’s and left a bag of mangos on her porch with a note that said, Thank you. She wasn’t home. Maybe that was better. Gratitude doesn’t always need a ceremony.

On the way back, I passed the manufacturing plant where my father had worked. A new banner fluttered on the chain-link fence announcing a job fair. For a second I pictured walking in, finding him, saying something cool and adult that would close a loop without reopening wounds. The light turned green before I could decide if that kind of neatness was what I wanted. I drove on.

A month later, Gabriel texted me for the first time in a year. He sent a photo of a coding project, lines of logic like a secret poem, and a message that said, I’m trying. I stared at the screen until the words steadied and replied, Good. Me too.

He wrote back, I’m sorry. For everything.

I typed and deleted and typed again. Finally: Thank you. Take care of yourself.

After that we traded messages occasionally. He sent a picture of a community college certificate. I sent a photo of the Safe Space office plant thriving. We kept it simple. Simple felt like a bridge you didn’t test by jumping.

The Watkins Foundation invited me to speak at their annual luncheon in a hotel ballroom where the water glasses sweated like they were doing the hard work. I stood at a podium that smelled faintly of polish and talked about tenants who are really people, about laws that are really choices, about how stability is a series of small, unglamorous wins. Afterward, a woman pressed a check into my palm and said, “I wish someone had told me this when I was nineteen.”

“I wish someone had told me a lot of things when I was nineteen,” I said, and we smiled like the kind of joke you tell when it’s not really funny but it binds you together anyway.

In December, the news did a follow-up piece. They caught me walking between the courthouse and our office carrying a stack of files and asked what had changed. “We have more resources,” I said. “And more responsibility. Landlords still have lawyers. Now more tenants do too.” It aired on a Thursday night. I didn’t watch. Eleanor texted the link with three fire emojis, which for her counted as an outburst.

That weekend I sat in my apartment with a mug of coffee and the quiet contentment of a list mostly checked. It was raining a steady California rain, the kind that made parking lots shine like spilled mercury. I thought of my mother for the first time in weeks and felt… not much. Not anger. Not longing. Some emotions die not in a blaze but like embers going gray.

I pulled up the Safe Space budget and moved a line item from “aspirations” to “available funds.” It was a small thing. It felt like a mountain shifting.

A year and a half after the trash bags on my porch, Safe Space represented a group of tenants whose building owner was trying to convert their apartments into luxury units by claiming uninhabitability and then refusing repairs. They were a patchwork of lives—an ICU nurse, a substitute teacher, a Lyft driver, a grandmother who watched three grandkids every afternoon. We trained them in how to document, how to request city inspections, how to show up at hearings en masse without letting nerves eat the case.

On the day of the hearing, the landlord’s lawyer showed up in a navy suit and a smirk. He called us “kids” twice. The hearing officer, a woman with a sharp bob and a sharper binder, let him finish and then asked me questions about the city’s relocation ordinance. I answered cleanly, my voice a length of cord I could hold.

The tenants won a stay. They got repairs. They stayed. We took a photo in the lobby afterward, not for social media but to text each other on bad days as proof that the machine could be hacked.

That night, Eleanor sent me a message: Proud of you. Simple. Exactly right.

I sat on my balcony with a blanket and listened to the rain tap the metal railing. I thought of my father’s voice saying “Education is your ticket” and wondered if he’d ever thought the destination might be a life in which his words were true and he wasn’t welcome in it. I thought of my mother’s hands and wondered if she had a new kitchen where they moved in circles she liked. I thought of Gabriel’s text and hoped his bridges were strong.

“What do you mean you don’t have the keys?” I had asked a lifetime ago. The truth was I had them now. Not to the house in Bakersfield with the maple out front, but to rooms I’d built and rooms I could enter because I knew where the latch was. The keys were knowledge. Community. A bank account that meant I could say no. A plant thriving in bad light. A program with a name that made people straighten.

Sometimes I drove past neighborhoods where landlords parked Teslas next to buildings that coughed paint and felt the old anger flare like a match. It was useful, that fire, if you learned to cup it in your palm and not let it burn you. Sometimes I bought mangos and left them where someone might find them and feel seen.

People asked me what happened with my parents and I learned how to tell it without apologizing or performing. “We don’t speak,” I said. “It was their choice first. Then it was mine.” If they asked if I would ever reconcile, I said, “Maybe. If they can tell the truth.” And then I moved the conversation back to housing code because some doors stay closed for a reason.

On the second anniversary of Safe Space, the city council issued a proclamation that landed in our inbox with a digital seal and an invitation to a meeting where we’d get a paper one. I printed the PDF and taped it crooked on our office wall and laughed until Marcus fixed it with an engineer’s precision. We ordered cupcakes. We kept taking calls.

I sometimes wished I could hand the version of me standing on that sidewalk in Bakersfield a fast-forward button. Show her the office with the window, the students who learned how to say “no” in a voice the world believed, the tenants who cooked dinner in kitchens where the ceiling no longer leaked, the steady paycheck, the plant. She’d still have to go through it. That’s the thing no one tells you about tunnels. The only way out is through. But maybe she’d walk a little faster if she knew what waited on the other side.

The night after the proclamation, I pulled the cracked beach photo from the back of my drawer. The glass was long gone. The edges were soft from handling. I looked at our faces and felt the complicated thing you feel when history is a house you moved out of but can’t quite tear down. Then I put the photo in a new frame. Not to display. To preserve. There is a difference.

I texted Gabriel a picture of the proclamation. He sent back a string of exclamation points and, a minute later, a photo from inside a modest apartment—desk, laptop, a sticky note that said function first. Progress is rarely cinematic. It’s desks and sticky notes and a plant that finally takes to its pot.

When the interviewers asked me what Safe Space’s secret was, I said it out loud like a recipe anyone could cook: Listen hard. Tell the truth. Don’t leave people outside in the rain and call it character building. The truth made rooms warmer. It paid for a thing or two.

“Sometimes the family you build is stronger than the one you’re born into,” I told the crowd at the luncheon and felt the room nod in a way that meant they understood and maybe they needed to hear someone else say it first.

The evening I finally felt done with the story of how I became who I was started out ordinary. I left the office with a tote bag heavier than regulation and crossed a parking lot shimmering with heat. I drove home, watered the plant, answered three emails I could have ignored, and made pasta with garlic because sometimes carbs are doctrine. I poured a glass of wine and stood at the window while a neighbor in a hoodie jogged past with a dog whose ears flapped like flags.

I thought about the house in Bakersfield exactly long enough to realize I hadn’t thought about it in weeks. The maple would be taller now. The door would still be red. Somewhere my parents were living a life that didn’t include me. Somewhere my brother was writing code that made something work. Somewhere a student who came through our door was cooking in a kitchen without a bucket catching drips. The world kept turning. This felt like peace.

I turned off the light and let the dark be what it is—an interval, not a verdict. The keys were on the counter. They were mine.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load