There was a tiny American flag magnet on the whiteboard across from my hospital bed, right next to the dry-erase note that said “ELAINE – OBSERVATION – ER ROOM 12.” The red, white, and blue looked almost absurdly cheerful under the harsh fluorescent lights. My phone lay on the blanket beside me, screen glowing with a text from my father that made the room feel even colder than the air-conditioning already had.

Can’t this wait? We’re busy.

The letters blurred and sharpened as my eyes filled with tears. A doctor had just told me I needed emergency surgery to stop internal bleeding. Because of a rare reaction to standard anesthesia, hospital policy required a family signature on a higher-risk protocol. I had already tried calling both my parents three times. No answer. No call back. Just that text.

Three weeks from that moment, I would sit in my grandfather’s living room with a navy-blue folder on the coffee table between us, papers inside that would change our family forever. But lying there in the ER, listening to the monitors beep and watching that little flag magnet tremble each time someone walked past the door, I made a different promise first.

If I lived through this surgery, I would never again let anyone treat my life like a scheduling inconvenience.

My name is Elaine Wilson, and I had just turned twenty-five a few weeks before that night. For most of my life, I believed what a lot of kids believe: that “family” is supposed to mean automatic support, unconditional love, the people who come running when something terrible happens. I clung to that belief through a childhood full of little disappointments, brushing them off as misunderstandings and busy schedules. I told myself my parents loved me, even if they had a strange way of showing it.

From the outside, the Wilsons looked like a picture-perfect middle-class family in suburban Chicago. We lived in a two-story beige house with a trimmed front lawn, potted geraniums by the porch steps, and a realty sign with my parents’ smiling faces staked in the yard more often than not. Our fridge was covered in glossy postcards advertising open houses they were hosting. Our Christmas card always showed us in coordinated sweaters, my parents front and center, me slightly to the side, one step back.

Arthur and Janet Wilson were the power couple of Lincoln Heights. They had built Wilson & Wilson Realty from scratch, at least that was how they told the story. By the time I hit high school, they were the kind of agents whose faces people recognized from bus benches and local billboards. They knew every lender, every contractor, every PTA president who might want to upsize to a four-bedroom colonial with a three-car garage.

Neighbors used to say things like, “Your parents are such hard workers,” and “Elaine, you must be so proud.” I would smile and nod and say, “Yeah, they really are.” No one saw the piano recitals where I scanned the audience again and again, only to see empty chairs where my parents should have been. No one watched me blow out birthday candles two hours late because they’d had a last-minute showing they just couldn’t miss, arriving with expensive gifts and flustered apologies that never really sounded like apologies.

“Business first, Elaine,” my dad would say anytime I looked even slightly disappointed. “This business puts food on the table and that roof over your head. Never forget that.”

My mom had a softer tone but the exact same script. “Your father knows best,” she’d remind me when I dared to ask why they missed another school play. “We’re building this business for your future.”

As a kid, what was I supposed to do besides believe them? I internalized the idea that my needs came third, after the business and their clients. I learned to microwave frozen dinners and eat alone in front of the TV. I pretended it didn’t sting when other parents showed up to school events in wrinkled work clothes, still wearing name badges or scrubs, while my reserved seat stayed empty.

The one person who consistently showed up was my grandfather, my dad’s father, Frank Wilson.

Grandpa Frank was everything my father wasn’t. Where Dad was sharp and always in motion, Grandpa was steady and present. Where Dad measured value in commissions and square footage, Grandpa measured it in time spent and stories shared. After my grandmother passed away when I was seven, Grandpa seemed to pour all the love he had left into being the best grandfather he could be.

When my parents missed my eighth-grade graduation for a “can’t-miss listing appointment,” Grandpa sat in the front row with a bouquet of grocery-store flowers and whistled so loudly when they called my name that a few teachers jumped. He took me out for ice cream afterward and let me talk about my favorite teachers, my friends, my dreams. He listened like every word mattered.

When I made honor roll in high school and my parents responded with a distracted, “That’s nice, honey,” without looking up from their laptops, Grandpa showed up the next day with a leather-bound journal in my favorite deep teal color.

“For a scholar,” he said, his eyes crinkling with pride. “So you remember your own words matter.”

That journal became one of my first hook objects, though I didn’t have language for that then. It sat on my nightstand through high school and college, a reminder that someone in my family saw me as more than an accessory in their success story.

Despite the emotional gaps at home, I carved out my own path. I earned a partial scholarship to Illinois State University, majoring in legal studies. When financial aid didn’t cover everything, I worked part-time jobs—tutoring, front desk shifts, whatever I could get. My parents could have helped more. They chose not to.

“You need to learn the value of hard work,” my dad said when I asked if they could co-sign on campus housing freshman year. “We built what we have with no one bailing us out. You’ll appreciate things more if you earn them.”

I watched them say that and then buy a vacation condo in Florida that they used three times in two years.

After graduation, I landed an entry-level position as a paralegal at Goldstein & Associates, a small but respected law firm downtown. The salary was modest, the hours demanding, but it was my first real step into the legal world I’d worked so hard to join. When I got the offer, I cried in my tiny off-campus bedroom, clutching the letter like it might disappear, then called my parents, hungry for their approval.

“Law firms are fine for getting experience,” my father said, the way someone else might say “training wheels.” “But real estate is where the real money is. When you’re ready to join a truly successful family business, just say the word.”

I never said the word.

Instead, I worked late and volunteered for tough assignments. I learned to navigate stubborn printers and complex filing systems and attorneys who could be brilliant and impossible in the span of ten minutes. After my first year, my boss, Martin, called me into his office.

“You’ve done solid work, Elaine,” he said, sliding a paper across his desk. “We’re bumping you up from junior paralegal to paralegal. Fifteen percent raise, more direct client contact. You’ve earned it.”

Fifteen percent wasn’t going to turn me into a millionaire, but it meant I could breathe a little easier. It meant I could finally stop taking the bus an hour and a half each way.

Three months before the accident, I bought my first car: a used silver Honda Civic with seventy thousand miles on it and a faint coffee stain on the passenger seat. I paid for it with my savings, a little help from a low-interest credit union loan, and a ridiculous amount of pride.

“It’s not glamorous,” I told Grandpa when I drove it over to show him. He stood in the driveway of his single-story ranch in Elmhurst, hands on his hips, grinning like I’d pulled up in a brand-new Corvette.

“It’s yours,” he said. “That’s plenty glamorous.”

My parents were less impressed. One Sunday, I drove the Civic to their house for dinner, heart light from my recent promotion and finally having a car that didn’t belong to a rental agency or my roommate.

Dad walked around it once, his expression unreadable, then tapped the hood like he was appraising a fixer-upper.

“This is exactly why you should think seriously about real estate,” he said. “You could be driving a BMW by now instead of… this.”

“I like ‘this,’” I said, patting my own car like it was a loyal dog. “It gets me where I need to go.”

He just shook his head, disappointed in a way that had nothing to do with safety ratings.

My apartment was another point of quiet pride. It was a third-floor walk-up in an older brick building in the city. The hardwood floors creaked, the cabinets were probably older than I was, but the rent was reasonable and the commute manageable. With Grandpa’s guidance, I’d transformed thrift-store furniture into something that felt cozy and mine. We spent weekends in his garage sanding an old coffee table and staining a hand-me-down dresser, the smell of sawdust and coffee mixing in the air.

“Your grandmother and I started with less than this,” he told me as we brushed varnish onto the table. “The trick isn’t the size of your house, kiddo. It’s the love you put inside it.”

My neighbor across the hall, Cassandra, became one of my few local friends. She was a nurse at Chicago Memorial Hospital and worked rotating shifts that sometimes matched my late nights. We developed a ritual of shared takeout on Sunday mornings or a glass of wine on random Tuesday nights, trading stories about demanding partners and equally demanding patients.

Two weeks before the accident, when I told her about my promotion, she raised her coffee mug in a toast.

“Look at you, moving up in the world,” she said. “Next thing I know, you’ll be my lawyer when I get sued for telling a surgeon what I really think.”

We laughed. I called my parents that night too, still hoping for something resembling pride.

“That’s nice, honey,” my mom said. I could hear muffled voices in the background, the clink of plates at some networking dinner. “We’re just walking into a meeting with potential investors for a new office, can we call you back?”

They never did.

When I told Grandpa, he insisted on taking me to my favorite Italian place to celebrate. He wore his good shirt and an old baseball cap with a faded American flag stitched on the brim, the one he’d gotten at a Fourth of July parade years earlier.

“You’ve built this life on your own terms,” he said, lifting his glass of house red. “That takes guts, Elaine. I’m proud of you.”

I had no idea how much more courage I would need in the weeks that followed.

The day everything changed was a Wednesday—April 15, tax day. It had rained on and off all afternoon, one of those early spring storms that couldn’t decide if it wanted to drizzle or pour. I stayed late to help Martin organize last-minute filings for clients who had treated the April 15 deadline like a vague suggestion.

“Drive safe, Elaine,” he called as I shut down my computer around nine. “The roads are a mess tonight. We need you in one piece around here.”

“Copy that,” I said, shrugging into my blazer.

The parking lot glistened under the streetlights, puddles reflecting the city skyline. I ran to my Civic, using my blazer as a makeshift hood, my heels splashing as I went. Inside the car, I cranked the heat and flipped on the wipers. They swished back and forth, already fighting to keep up.

On the expressway, the storm turned mean. Sheets of rain hammered the windshield, turning headlights into smeared streaks of white and red. I slowed down, leaving extra space between my car and the pickup truck ahead of me. Grandpa’s voice echoed in my mind like it often did on nights like that.

“On bad roads, it’s not just about how you drive,” he’d say. “It’s about how everyone else drives too. Assume someone out there is about to do something stupid and be ready.”

I wish I could tell you that looking back I noticed some sign, some hint. I didn’t. One second, I was humming along with the radio, planning to microwave leftover pasta when I got home. The next, there was a blast of blinding headlights crossing the median.

Later, police reports would say the other driver’s blood alcohol level was twice the legal limit. Later, they would reconstruct every skid mark and impact point, connect every terrible dot. In the moment, all I knew was that a pickup truck was suddenly in my lane, barreling straight toward me.

My hands tightened around the steering wheel. I jerked it right, hard. The world turned into sound and impact and chaos: metal shrieking, glass popping, the gut-punch slam of the airbag exploding into my face. The car spun once, twice, three times maybe, then smashed sideways into the guardrail. Pain flared everywhere at once, sharp and white-hot. Something warm slid down my temple. The world narrowed to the sound of rain hitting the crumpled hood and, somewhere far away, a siren wailing closer.

The next thing I knew, I was waking up to beeping monitors and a ceiling painted a beige that only exists in hospitals. My chest felt like it had been squeezed in a vise. My left leg was propped up and strapped into some kind of brace. When I tried to move my right arm, nothing happened, like it had been disconnected.

“Easy,” a voice said. A tall man in a white coat leaned into my field of vision. “I’m Dr. Montgomery. You’re at Chicago Memorial Hospital. You were in a car accident.”

“How bad?” My voice sounded like someone else’s, thin and scratchy.

“You’ve got three broken ribs, a fractured femur, a dislocated shoulder, and a concussion,” he said, checking the monitors. “There’s also internal bleeding we need to address surgically.”

Internal bleeding. Surgery. The words floated like labels I couldn’t push together.

“You’re actually lucky,” he added, in that clinical way doctors sometimes have. “The driver of the other vehicle didn’t survive.”

Guilt and shock collided in my stomach. Someone was gone. Someone whose face I hadn’t even seen.

“The internal bleeding is our main concern,” Dr. Montgomery continued. “We need to get you to surgery in the next few hours. But there’s a complication. Your chart shows you had a reaction to standard anesthesia during your wisdom tooth extraction three years ago?”

I nodded slightly, remembering throwing up for twelve hours and waking up disoriented and shaking.

“The alternative protocol we want to use has a slightly higher risk profile. For patients under a certain age with these kinds of complications, hospital policy requires documented consent from a family member or legal proxy.”

He said it apologetically, like he already knew this was an extra layer of trouble I didn’t need.

“I live alone,” I said slowly, through the haze of pain. “But my parents… they’re alive. They’re in Lincoln Heights.” I gave him their numbers. “They’ll come.”

A nurse with kind eyes and a badge that said HEATHER helped me make the calls. My mother’s phone went straight to voicemail. My father’s rang and rang before flipping to the same robotic message. I left one message, then another, then a third, my voice sounding more desperate each time.

“Mom, it’s me. I’ve been in an accident. I’m at Chicago Memorial. They need consent for surgery. Please call me back.”

“Dad, I really need you to call me. I’m in the ER. The doctors need your consent for an emergency procedure. Please call the hospital.”

An hour crawled past. Then another. Heather stopped by between other patients, adjusting my IV, offering small talk, a cup of ice chips, anything to distract me from the clock. The pain meds they’d given me in the ER were wearing off, but they couldn’t administer the next set until anesthesia had finalized a plan.

Finally, my phone buzzed.

I fumbled it up to my face. It was a text from my father.

Just got your messages. Can’t this wait? We’re busy with the Henderson property showing. Big clients. Call tomorrow.

For a second, I honestly thought I’d misread it. I blinked hard. The words stayed the same.

Heather must have noticed something on my face, because she leaned closer. “Everything okay?”

Instead of answering, I turned the phone around so she could read the text herself.

For a split second, her professional mask slipped. Shock, then anger, flashed through her eyes before she smoothed her expression.

“I’m going to get the social worker,” she said quietly. “We’re going to figure this out, okay?”

I tried one more time anyway, fingers trembling as I typed.

Dad, I need emergency surgery. They need consent now. Please come to Chicago Memorial ER.

His reply came three minutes later.

We’ve got back-to-back showings all day. Your mother says take whatever medication they recommend. We’ll try to stop by this weekend.

That was the line that broke me. Not the metal against metal on the highway, not the news that someone hadn’t survived, not even the laundry list of injuries the doctor had rattled off. It was that text.

The people who were supposed to show up when I was at my most vulnerable were telling me my life had to wait its turn behind a property listing.

Tears rolled into my hair as sobs clawed at my chest, making my broken ribs scream. I clutched the phone like it might morph into something else, some message that made sense. Heather came back with another woman in a blazer and a badge that said PATRICIA – SOCIAL WORK.

“Elaine,” Patricia said gently. “I’m so sorry. Heather showed me the messages. Is there anyone else we can call? Another relative who could come sign for you?”

Through the panic and pain, one name cut through.

“My grandpa,” I said, my voice shaking. “Frank Wilson. He’s in Elmhurst. He’ll come.”

Patricia stepped into the hall to make the call. Heather stayed, rubbing my forearm carefully, mindful of the IV line.

“He’s on his way,” Patricia said when she came back. “He said he’ll be here within the hour.”

Despite living forty-five miles away, Grandpa arrived in just under fifty minutes. I know because I watched the red numbers on the wall clock like my life depended on them. Maybe in a way, it did.

He burst into the ER bay with the energy of a man twenty years younger, his silver hair mussed, his old flag-brimmed cap clutched in one hand.

“Ela,” he said, taking my good hand in both of his. “My girl. What on earth…”

His voice cracked. I’d never heard my grandfather sound scared before. Concerned, sure. Stern, sometimes. But not scared.

Dr. Montgomery reappeared and explained my injuries again, this time to Grandpa, going over the alternative anesthesia, the risks, the timeline.

Grandpa listened carefully, eyes narrowed, asking smart, practical questions about recovery and aftercare. When Patricia handed him the consent forms, he read every line before signing with a steady hand.

“I’m not agreeing to this because I’m not worried,” he told the doctor. “I’m agreeing because I trust you know what you’re doing more than I do. Just… do everything you can for her.”

“We will,” Dr. Montgomery said.

As they prepared to wheel me toward surgery, Grandpa leaned down and kissed my forehead.

“I’m going to be right here when you wake up,” he said. Then, under his breath but still audible, “I don’t know what’s wrong with that son of mine, but this isn’t right. Not right at all.”

The last thing I saw before the operating room lights swallowed everything was the small American flag magnet on the ER whiteboard, tilting slightly from where someone had bumped it. For some reason, that image stayed with me.

When I woke up again, the lights were softer. The beeping was slower. My throat felt raw, and I had a dull, heavy ache in my chest and leg instead of the sharp, stabbing pain from before. I blinked until my vision focused.

Grandpa was in a plastic chair beside my bed, his flag-brimmed cap resting on his knee, a crossword puzzle half-finished in his lap. His glasses sat crooked on his nose. He jerked awake the second I stirred.

“There she is,” he said, his voice thick with relief. “Welcome back, kiddo.”

“How…” I swallowed painfully. “How bad?”

“They got all the bleeding stopped,” he said. “Set your leg. You’re a mess, but Dr. Montgomery says you’re going to be okay. It’s going to take time, but you’re still here. That’s what matters.”

“My parents?” I asked, even though I already knew part of the answer.

His jaw tightened.

“I called them after you went into surgery,” he said. “Left messages. No call back yet.”

Another tiny crack in the illusion I’d been carrying around for years.

Over the next five days, Grandpa practically moved into my hospital room. He brought a thermos of his homemade chicken soup because, in his opinion, hospital food “looked like it lost the will to live.” He asked Cassandra to grab some of my things from my apartment—soft pajamas, my phone charger, that teal journal from my nightstand—and set them up so the room felt less like a rental cell and more like a temporary home.

He held my hand during painful dressing changes when I was sure I couldn’t handle one more needle or tug at my stitches. He made the physical therapist laugh, which made me laugh, which somehow made the hurt bearable.

My parents texted exactly once on day two.

Hope you’re feeling better. Spring market is crazy. We’ll try to visit when things calm down.

They didn’t visit. Not that day. Not the next. Not the next.

Every time my phone lit up, I felt a flicker of hope that maybe it was them saying, “We’re here, we’re sorry, we’re on our way.” It never was. It was Martin checking in, or Cassandra sending a meme, or a spam call about my car’s warranty.

Nurse Heather became more than just a nurse. She’d swing by even when she wasn’t officially assigned to me, sometimes with an extra pudding cup or a story about some ridiculous thing that had happened on another floor.

“Your grandfather is something else,” she said on day four, chart in hand as Grandpa argued with the TV about a baseball game. “I don’t think he’s left this room for more than fifteen minutes at a time.”

“He’s always been like that,” I said. “When he decides you’re his, he doesn’t let go.”

“Some people understand what family means,” she said, glancing at my silent phone. “Others need a lesson or two.”

By day five, the conversation shifted to what came next. Dr. Montgomery stood at the foot of my bed with a team—a case manager, a physical therapist named Marcus, and Patricia the social worker.

“You’re healing well enough that we can start planning for discharge,” Dr. Montgomery said. “But we have to be realistic about your limitations. You won’t be able to manage stairs for at least six weeks. Your apartment building doesn’t have an elevator, right?”

“Third-floor walk-up,” I said, already knowing where this was going.

“You’ll also need help with daily activities until your shoulder is strong enough to begin formal physical therapy,” Marcus added. “Bathing, dressing, food prep. It’s a lot for one person, even without the leg.”

“Is there someone you can stay with?” Patricia asked. “Or someone who can come stay with you?”

Before I could answer, Grandpa spoke up.

“She’s coming with me,” he said. “My house is one level. I’ve already cleared out the guest room, moved in a recliner, everything. I can build a ramp over the front steps.”

Patricia hesitated, looking at his chart. “Mr. Wilson, caregiving after this kind of trauma is intense. At your age, we just want to make sure—”

“At my age, I know what matters,” he said, not unkindly but firmly. “I’m healthy. I’m retired. My schedule is wide open. She’s my granddaughter. That’s the beginning and end of the conversation.”

That was one of the hinge moments of my life, though I didn’t recognize it until later. While my parents were too busy to show up, my seventy-four-year-old grandfather was rearranging his entire life without hesitation.

Not long after the care plan was set, my phone finally rang with my parents’ number. I looked at Grandpa. He raised his eyebrows as if to say, “You’re in charge.” I put it on speaker.

“Elaine, it’s Mom,” she said. “Your dad and I were talking. We’re sorry we haven’t been able to visit. Spring market is just… insane.”

No “How are you?” No “We’re so glad you’re okay.” Just market talk.

“The doctors say I can’t go back to my apartment,” I said, trying to keep my voice level. “I can’t do stairs for at least six weeks.”

There was a pause, then muffled voices, like she’d covered the receiver.

“Well, honey,” she said finally, “our schedule is so unpredictable with showings and open houses. And the guest room is full of staging furniture right now. We’re just not set up for medical equipment and all that.”

“I’m going to stay with Grandpa,” I said. “He’s already set everything up.”

“Oh.” She sounded genuinely relieved. “Well, that’s probably best then. We’ll try to come by Sunday if the open house wraps early enough.”

They didn’t.

Moving into Grandpa’s ranch-style house in Elmhurst felt like stepping into a different world. The exterior was modest—white siding, a small porch with a hanging fern, a little metal mailbox with a tiny American flag sticker on the side—but inside it felt like safety. The guest room had been transformed into a recovery nest: extra pillows, a stack of books, a bell on the nightstand that Grandpa swore was “for emergencies only, but don’t you dare hesitate if you need anything.”

We settled into a routine. Mornings started with the smell of bacon or oatmeal, Grandpa easing me out of bed, helping me into a bathrobe and to the bathroom in a slow, careful shuffle. Home health nurses came three times a week. Marcus showed up with his therapy bag, gently torturing my leg and shoulder while cracking jokes about how I was doing better than half his teenage athletes.

“You’re stubborn,” he told me more than once. “That’s going to serve you well.”

Evenings were my favorite. After dinner—usually something simple but hearty like pot roast or chicken casserole—we would sit in the living room, the TV murmuring in the background. Sometimes we watched old movies. Sometimes we played cards. Sometimes we just talked.

It was during one of those evenings, spoons scraping the last of the ice cream from our bowls, that Grandpa finally talked about my dad.

“Arthur’s always wanted more,” he said quietly, staring at the family photos on the mantle. “Even when he was a kid. If he had one toy, he wanted two. If his friend had a ten-speed, he needed a twelve-speed.”

I could see it. Not just in cars and toys, but in everything. Listings, commissions, square footage. More, more, more.

“Your grandmother and I tried to teach him gratitude,” Grandpa went on. “Tried to show him that enough can be enough. But some lessons don’t stick.”

“Why didn’t you ever say anything to them about how they treated me?” I asked, not accusing, just… curious.

His shoulders sagged a little.

“I did,” he said. “When you were younger. Told him he was missing the best years, that he was going to look up one day and realize he’d worked through all the moments that matter. He told me I was stuck in the past. Said I was jealous of his success. After a while, I realized pushing him only made him dig in deeper. So I decided to focus on you instead.”

He looked at me with such a mix of sadness and pride that my throat tightened.

“I’ve spent years worrying I failed with him,” he admitted. “That I didn’t teach him right. But seeing you? Maybe I didn’t fail completely.”

That was another hinge sentence in my story. For the first time, I let myself consider that my parents’ behavior said more about them than it did about me.

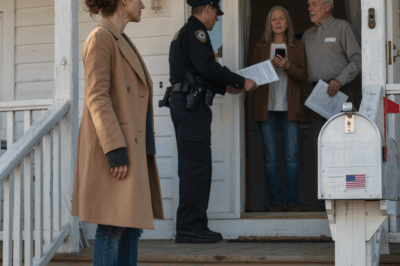

Two weeks into my stay at Grandpa’s, my parents finally showed up in person.

They pulled into the driveway in Dad’s BMW, engine purring like it owned the street. Dad stepped out first, sunglasses still on even though it was overcast. Mom followed in a sleek blazer and heels that sank slightly into the grass.

“The house looks smaller than I remember,” Dad said as he stepped inside, looking around like he was evaluating a listing.

“Not everyone needs four thousand square feet to be happy, Arthur,” Grandpa replied mildly.

Mom made a fuss over me, fluffing my blanket, asking surface-level questions about my pain scale and whether the nurses were “nice.” Dad paced, checking his smartwatch every few minutes.

“So when do they think you’ll be back at work?” he interrupted while I was explaining physical therapy. “You don’t want to lose that job. Small as it is, it’s still a foothold.”

“The doctors say at least another month before part-time,” I said. “My firm’s been understanding.”

“A month?” He frowned. “That seems… excessive for a few broken bones.”

“She nearly died, Arthur,” Grandpa said quietly. “The internal bleeding was serious.”

Dad waved his hand like he was brushing away a fly.

“Well, the important thing is getting back to normal as quickly as possible. You can’t afford to be seen as unreliable.”

They stayed exactly forty-seven minutes. I know because I watched the stove clock tick from 2:13 to 3:00 while they talked mostly about themselves.

As Grandpa walked them to the door, I heard my father’s voice drift back to the living room.

“This whole situation is so inconvenient,” he muttered. “We could’ve used her help with the spring listings.”

“At least your father is handling it,” Mom replied. “Can you imagine if she’d expected to stay with us, with our schedule?”

The front door closed. Grandpa came back into the living room, schooling his features into something neutral.

“They mean well,” he offered.

“Do they?” I asked.

He didn’t answer.

The next day, Cassandra dropped off a stack of mail from my apartment. Among the junk flyers and credit card offers were hospital bills and insurance statements. I spread them out on the dining table, the numbers adding up in a sickening way.

Even with decent health insurance, the accident was going to be expensive. There were deductibles and co-pays, out-of-network charges, physical therapy bills, and the looming fact that my car had been totaled. My savings would cover some of it, but not all. I could feel panic prickling at the back of my neck.

“Hey,” Grandpa said, resting a hand on my shoulder. “One step at a time. We’ll figure this out.”

The next morning, I called my insurance company to get a clearer picture. The representative pulled up my file and began rattling off claim numbers and billing codes. Then she said something that made my stomach drop.

“And of course, we’ve already spoken with your parents a few times about potential settlements,” she said.

“I’m sorry, what?” I interrupted. “You’ve spoken to my parents?”

“Yes,” she replied. “They’re listed as secondary contacts and financial proxies on your policy. They called three days after the accident to ask how any settlement funds would be disbursed.”

“I never listed them as proxies,” I said slowly. “I’m an adult. I handle my own accounts.”

There was a pause as she scrolled.

“It looks like those designations were added about two years ago,” she said. “Around the time your employer benefits were set up.”

Two years ago. When I’d started at Goldstein & Associates. When Dad had offered to “help” me set up my benefits because, in his words, “That legalese will make your head spin.”

He had sat at our kitchen table with my laptop in front of him, walking me through selections while I tried to absorb it all. I remembered being grateful. I remembered him saying, “Let me handle some of this. It’s what I do.”

Apparently, he’d handled more than I knew.

It got worse. Further down the rabbit hole, I discovered my parents had also contacted my auto insurance, asking questions about how vehicle replacement funds could be released and who would be listed as payees. They had spoken to my apartment’s property manager about “possibly terminating the lease due to medical hardship,” without a single conversation with me.

I called my father. This time, he answered on the first ring.

“Elaine,” he said, sounding brisk. “I was just going to call you. Good news about the car. I think we can push the insurance toward a reasonable settlement if we—”

“Why are you listed as a beneficiary and financial proxy on my policies?” I cut in.

He went quiet for a beat.

“That’s just practical,” he said. “Insurance companies are a nightmare. They need to deal with someone who knows how to negotiate. You’re young. You don’t understand how these things work yet.”

“You’re a real estate agent,” I said. “You don’t have legal or insurance training. And you didn’t tell me you were doing this.”

“Now, don’t be ungrateful,” he said, irritation creeping in. “Your mother and I are trying to help. These medical bills are going to be significant. We think it would be wise for you to move back home for a while so we can keep an eye on things. At least until the settlement—”

“The settlement,” I repeated. “What is it you think you’re keeping an eye on?”

There was another pause, longer this time.

“If you must know,” he said, his tone turning defensive, “we’ve been presented with an opportunity to expand the business. A second office in Oak Park. Prime location. The timing aligns with your situation. The adjuster mentioned a settlement in the seventy-two-thousand-dollar range. If we invest that into the business now, it will multiply over time. It’s a family enterprise, Elaine. Everything we do benefits you in the long run.”

Seventy-two thousand dollars. My injuries, my totaled car, my weeks of pain and fear—he was already mentally using them as seed money.

“So you were planning to use my accident settlement to fund your expansion,” I said.

“That’s a very negative way of looking at it,” he replied. “We’re consolidating family resources.”

I hung up. For a moment, I just stared at my reflection in the darkened TV screen, the bruises blooming across my face, the cast on my leg, the sling around my shoulder. Then the sobs came, hot and choking. Every instance of them choosing business over me, every empty seat and broken promise, crashed over me in one wave.

Grandpa found me like that, curled on the couch, shaking.

“What happened?” he asked, eyes going flinty when I told him about the proxies, the settlement, the Oak Park office, the seventy-two thousand dollars my parents apparently thought they had first claim to.

By the time I finished, his jaw was clenched so tight a muscle in his cheek jumped.

“This ends now,” he said, his voice low. “I’ve stood back long enough.”

“What can we even do?” I asked, swiping at my cheeks. “They’re my parents. They’re on everything.”

“We start by talking to someone who knows more than they do,” he said. “Tomorrow, we’re calling Allan.”

“Allan?”

“Allan Reynolds,” Grandpa said. “We worked together years ago when your grandmother and I drew up our wills. Family law, estate planning. Smart as a whip. Retired now, but he’ll know exactly what to do.”

The next morning, Allan arrived with a leather briefcase and a pair of sharp blue eyes behind wire-rimmed glasses. He and Grandpa greeted each other like old comrades.

“Frank doesn’t exaggerate,” Allan said after I’d laid out everything: the accident, the texts that night, the proxy designations, the phone call about the seventy-two thousand dollars. “So when he told me something was wrong here, I knew it had to be serious.”

He opened a navy-blue folder on the dining table and began taking notes, his pen scratching methodically.

“What you’re describing is a pattern of financial overreach and emotional neglect,” he said when I finished. “On paper, you’re an adult with full capacity. They have no legal right to manage your affairs without your consent. Adding themselves as proxies and beneficiaries without your clear understanding crosses several lines.”

“So what can we do?” I asked.

“A few things,” he said. “First, we remove them as beneficiaries and proxies everywhere we can. That means new forms, new designations, and in some cases, entirely new accounts. Second, we put your financial institutions and insurers on formal notice that your parents do not have authority to act on your behalf. Third, we create a legal power of attorney that names someone you trust to make decisions if you’re ever incapacitated again. Because right now, by default, your parents would be next in line.”

“I want Grandpa,” I said, without hesitation. “If he’s willing.”

Grandpa reached over and squeezed my hand.

“Of course,” he said. “If that’s what you want, I’m honored.”

“As for the insurance settlement,” Allan continued, “we’ll send a cease-and-desist letter regarding their involvement. Any attempt by them to redirect or claim those funds could be considered attempted fraud.”

He slid a blank sheet of paper from the blue folder toward me.

“Start making a list of every place they might be connected to your finances,” he said. “Banks, credit cards, insurance, anything. We’re going to build a wall between you and their access.”

That blue folder became our new hook object. First gợi mở as a simple office supply, then slowly filling with copies of forms and letters and draft documents that represented something much bigger than paper.

Later that week, my college friend Jessica—now a financial adviser—came by after work. She frowned as we spread my statements on the table.

“I knew your parents were intense about money,” she said. “But this is something else. They’ve basically woven themselves into every seam of your financial life.”

Together, we opened new bank accounts at a different institution, redirected direct deposits, and changed online passwords. Jessica set up credit monitoring and alerts so I’d know if someone tried to open anything in my name.

“This is going to take time,” she said, “but you’re doing the right thing. And once the seventy-two thousand hits, it’ll go where you decide, not where they do.”

As we worked behind the scenes, life continued. My days were a mix of physical pain, slow improvements, and small joys. Marcus pushed my leg a little further each session. Nurse Heather stopped by on her day off with homemade cookies. Martin from the firm called regularly.

“Don’t you worry about your job,” he said. “Focus on healing. The office is chaos without you, which is a strong argument for giving you another raise when you get back.”

But my emotional injuries were still raw. That’s where Dr. Rivera came in, a therapist Patricia had recommended. She started with weekly sessions at Grandpa’s house, sitting across from me in his den while I balanced a heating pad on my shoulder.

“What you went through with your parents in that ER is not an isolated incident,” she said after I described those nights. “It’s a culmination.”

We walked through my childhood, the missed recitals, the empty seats, the “Business first” mantra. The way I’d always assumed if I tried harder, they would show up.

“It’s common for children who grow up with emotional neglect to take the blame,” she said. “It’s easier to think, ‘If I were better, they’d treat me differently,’ than to admit, ‘They are choosing not to show up.’”

“What if I’m being unfair?” I asked. “What if I’m just… sensitive?”

“Let’s look at the facts,” she said calmly. “You were in a car accident. You needed emergency surgery. They refused to come because they didn’t want to disrupt a property showing. Then they tried to position themselves to benefit financially from your trauma. Is that sensitivity or reality?”

I didn’t have an answer. The truth sat in my chest like a stone.

Around the third week after the accident, Allan came back with the blue folder thicker than before.

“Everything’s ready,” he said. “New beneficiary forms. New power of attorney naming Frank. Letters to your insurers and banks. And a formal notification to your parents, informing them that they no longer have any legal authority over your affairs.”

“Do we have to mail it?” I asked.

“We could,” he said. “But sometimes, in family situations, delivering it in person is… clarifying. For everyone.”

Dr. Rivera agreed. “You’ve spent your whole life being talked over, minimized, ignored,” she told me. “Looking them in the eyes and saying, ‘This is what I’m doing,’ can be a powerful step in reclaiming your voice.”

Grandpa’s advice was simpler.

“Some things you need to say out loud so you can’t convince yourself later that they didn’t really happen,” he said. “Not for them. For you.”

So we planned a meeting for the three-week mark.

The morning of, I sat in the living room in real clothes for the first time in days—jeans over my brace, a soft sweater—and stared at the blue folder on the coffee table. Outside, Grandpa’s little flag sticker on the mailbox fluttered in the spring wind.

“You okay?” he asked, sitting down beside me.

“I’m terrified,” I admitted. “But also… ready.”

“That’s how big moments feel,” he said. “Scared and ready at the same time.”

Allan arrived early, set his briefcase down, and walked me through what would happen.

“Remember,” he said, “you’re not asking them to agree. You’re informing them of decisions already made. They can rant or refuse or storm out. The documents still stand. You always have the right to protect yourself.”

He took a seat slightly behind me, to my right. Grandpa sat slightly behind me on the left. The arrangement made it feel like I literally had people at my back.

At exactly two in the afternoon, the doorbell rang.

“I’ve got it,” Grandpa said, standing.

We heard my father’s voice immediately.

“Dad, this whole formal meeting thing is unnecessary,” he said. “If Elaine wanted to talk, she could have called. We’re in the middle of preparing for the Oak Park deal.”

“Some conversations deserve more respect than a phone call,” Grandpa replied. “Come on in.”

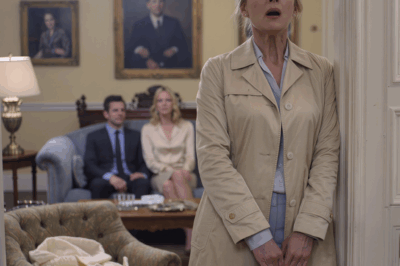

My parents walked into the living room like they were walking into a client’s closing. Dad wore pressed khakis and a polo shirt embroidered with the Wilson & Wilson logo. Mom wore a blazer and heels, hair perfectly smoothed.

Their gazes flicked to Allan, then the blue folder, then me with my crutches leaning nearby.

“What’s this about?” Dad asked, instantly suspicious. “And who is he?”

“This is Allan Reynolds,” I said. “He’s a family law attorney and Grandpa’s friend. Please sit down.”

They did, reluctantly.

“Business must be good if you can afford a lawyer,” Dad said with a tight smile. “Though I don’t see why you’d need one to talk to your own parents.”

I took a breath, feeling the weight of every hinge sentence I’d been building toward.

“I asked you here to talk about boundaries,” I said. “And about what happened the night of my accident. And what’s going to happen from here on out.”

Mom’s smile faltered. “Honey, we’ve already said we’re sorry we couldn’t be at the hospital. The market has been insane. If we had known how serious—”

“You did know,” I said, surprised at how steady my voice sounded. “I told you I was in the ER. I told you I needed emergency surgery. Dad, you texted, ‘Can’t this wait? We’re busy.’ You said you would try to stop by this weekend.”

Dad’s jaw tightened. “You’re taking that out of context,” he said. “We were in the middle of a very important showing. We couldn’t just abandon—”

“You mean the Henderson property?” I asked. “The one that didn’t even sell?”

That made him blink.

“This isn’t about one text,” I continued. “It’s about a pattern. For twenty-five years, you’ve made it clear that the business comes first. I’ve always tried to understand that. But when you treated my life-or-death surgery like a scheduling inconvenience, you crossed a line I can’t ignore.”

Mom’s eyes filled with tears. “Elaine, of course we care. We pay for your health insurance—”

“You don’t,” I said. “My employer does. And speaking of insurance, I know you contacted my health and auto carriers and listed yourselves as proxies without my knowledge. I know you spoke to them about how any settlement money would be disbursed. I know about the seventy-two thousand dollars you want to use to open a second office.”

Dad’s eyes flicked toward Allan, then back to me.

“We’re your parents,” he said. “Everything we do is for your future. That settlement could help us open an office that would eventually be yours.”

“It’s my settlement,” I said. “It’s compensation for my injuries. For my pain. Not seed money for your expansion.”

He opened his mouth, but I raised a hand.

“I’m not here to argue about motives,” I said. “I’m here to tell you what’s changing.”

I slid the blue folder across the coffee table. Dad stared at it like it was something that might bite him.

“These are documents Allan prepared,” I said. “They remove you as beneficiaries, proxies, and contacts on all of my accounts and policies. They formally revoke any authority you’ve given yourselves to act on my behalf. They name Grandpa as my power of attorney for both medical and financial decisions if I’m ever incapacitated again. And they instruct all relevant institutions to cease communicating with you about my affairs.”

Mom put a hand to her chest like she’d been slapped. “You’re cutting us out of your life,” she whispered.

“No,” I said. “I’m cutting you out of my finances. There’s a difference. I’m doing the bare minimum to keep you from turning my emergencies into your opportunities.”

Dad let out a short, harsh laugh.

“This is ridiculous,” he said. “We are your parents. We have a right to be involved.”

“Being a parent is more than biology,” I said quietly. “It’s showing up. It’s putting your child’s safety above your showings. It’s not planning how to spend seventy-two thousand dollars that doesn’t belong to you while your daughter is learning to walk on crutches.”

“You’re being dramatic,” he said. “You’ve let your grandfather poison you against us.”

Grandpa spoke for the first time.

“Arthur,” he said, his voice steady. “I sat in that hospital waiting room while surgeons cut into your child to stop internal bleeding. I signed my name on consent forms that should have had your signature. I watched her cry when she read your texts. No one had to poison her against you. Your own choices handled that just fine.”

Dad’s face flushed. “Stay out of this, Dad.”

“It’s my business when my granddaughter is hurt,” Grandpa said. “It always has been.”

Dad turned back to me. “If you sign these, you’re burning a bridge you can’t rebuild,” he warned. “When you come to your senses later, don’t expect us to welcome you back like nothing happened.”

I thought about all the times I’d waited for them to show up and they hadn’t. All the ways I’d shrunk myself to make room for their schedules. I thought about lying in that ER room under the American flag magnet, realizing that the people I thought would save me were busy selling someone else a house.

“I’m not burning the bridge,” I said. “I’m putting guardrails on it. You’re the ones who keep driving into oncoming traffic.”

Allan cleared his throat.

“Mr. and Mrs. Wilson,” he said, “these documents are valid whether you sign them or not. Your signatures simply acknowledge that you received notice. Refusing to sign will not change their effect.”

Dad glared at him, then at me.

“So this is what you want?” he asked. “To legally disown your own parents?”

“What I wanted,” I said, “was for my parents to care more about my life than their listings. What I wanted was for the people on my health forms to show up when the hospital called. What I wanted was never to need a blue folder full of legal documents to keep my family from treating me like an asset. But here we are.”

Mom reached for the folder with trembling fingers. Dad caught her wrist.

“Don’t,” he snapped. “She’s upset. She’ll regret this.”

I met Mom’s eyes.

“I might regret lots of things in life,” I said. “But I won’t regret protecting myself.”

Something in my voice must have landed, because she gently pulled her wrist free, opened the folder, and started reading. Dad paced. Mom signed first, her tears spilling onto the pages. Then, after a long, tense silence, Dad finally grabbed the pen from Allan.

He scrawled his name with angry strokes on every line Allan indicated.

“Is this what you wanted?” he demanded, snapping the folder shut and shoving it back toward me. “Congratulations. You’ve made your choice. Family loyalty goes both ways, Elaine.”

“You’re right,” I said. “It does. That’s why I can’t keep pretending this is normal.”

He stared at me like he didn’t recognize the person sitting in front of him.

“I don’t know who you are anymore,” he said finally.

“Maybe for the first time, I do,” I replied.

They left with stiff goodbyes and no hugs. The door closed with a muffled thud that felt surprisingly final.

In the quiet that followed, my hands started shaking. Grandpa moved to my side and wrapped his arm gently around my shoulders.

“I’m so proud of you,” he said simply. “You did the hard thing.”

The blue folder sat between us, thicker now, weighty in a way that went beyond paper. It had started as evidence. It was becoming a symbol.

That night, I slept harder than I had since before the accident. When I woke up the next morning, breathing felt easier, like I’d been holding my lungs half-full for weeks without noticing.

“You look different,” Grandpa said as he carried in two mugs of coffee. “Lighter.”

“I feel different,” I said. “Like I finally put down something heavy that wasn’t mine to carry.”

The practical work of rebuilding my life continued. Jessica helped me finalize the separation of accounts. We closed out old ones, opened new ones, redirected deposits, and set up a budget that took into account my medical bills, rent, and the timeline before I could return to work fully.

“You’re in better shape than you think,” she said, scanning the numbers. “You’ve been careful with money. Once the seventy-two thousand hits—and now that it’ll actually come to you—you’ll have a decent cushion.”

When my doctors finally cleared me for independent living with certain accommodations, Cassandra swooped in with good news.

“The ground-floor unit in our building just opened,” she said. “One bedroom, wider doorways, little patio instead of a balcony. Twenty dollars more in rent a month. I already hinted to the landlord that you might be interested. He’s willing to hold it until you can come see it.”

We managed a visit with me on crutches, Grandpa at my elbow. The apartment felt like a small miracle—sunny, accessible, familiar but new. I signed the lease on the kitchen counter, my signature steady, the ink drying next to a tiny American flag magnet the current tenant had left on the fridge door.

A few weeks after the confrontation, word began to filter back about the Oak Park office. Without the seventy-two thousand they’d been counting on, my parents’ financing fell apart. One of their longtime clients—who happened to be friends with Grandpa and had heard through the grapevine how they’d handled my accident—pulled his listing and went with another agency.

“That’s the thing about reputation,” Grandpa said when he told me over dinner. “You can plaster your name on every bus bench in town. But people still talk.”

I didn’t take any satisfaction in their setback exactly. It just felt… fitting. A small piece of social reality catching up to behavior that had gone unchallenged for years.

My return to work at the firm was gradual. At first, Martin sent me remote tasks I could handle from Grandpa’s dining table, files he needed organized and summaries he trusted me to draft. When my doctor finally cleared me to drive short distances, I went back to the office half-days, my desk rearranged so I didn’t have to twist my shoulder too much.

“The filing system fell apart without you,” Martin joked as he showed me a messy cabinet. “Consider this job security.”

Meanwhile, my relationship with my parents stayed… complicated. After the confrontation, there was silence for a while. Then, two weeks later, a single text from my mom.

We hope you’re feeling better. The door is open when you’re ready to apologize.

Dr. Rivera and I read it together in session.

“This is a classic deflection,” she said. “They’re positioning themselves as the wronged party. They’re saying, ‘We’ll forgive you when you stop insisting your experience is real.’”

“I want parents,” I said, staring at the text. “But I don’t want this.”

“You’re grieving the parents you wish you had,” she said. “That grief is real. And it’s separate from the boundaries you’re setting now.”

So I didn’t respond. Instead, I focused on the people who were showing up: Grandpa, who made me grilled cheese when I was too tired to cook. Cassandra, who helped me move into my new apartment and insisted on placing the teal journal and the blue folder on the top shelf of my closet, side by side.

“Just in case you ever forget how strong you are,” she said.

Heather invited me to join a casual hiking group for hospital staff and friends once I was strong enough to tackle easy trails. Marcus cheered when I cleared each new physical benchmark.

“You’re ahead of schedule,” he said one afternoon as I walked the length of his therapy gym without crutches. “That determination of yours? That’s your superpower.”

Six months after the accident, an envelope from my mother arrived in my mailbox. Her handwriting on the front made my heart do something complicated.

Inside was a letter, handwritten on plain stationery.

Elaine,

I’ve been doing a lot of thinking since our last meeting.

Your father is still very hurt and angry. He believes you’ve betrayed him. I’m starting to see a different picture.

The hospital sent over your medical records for insurance purposes. Reading them, seeing in black and white how close we came to losing you while I was deep-cleaning a kitchen for a showing, forced me to admit some things I’ve been avoiding.

I don’t like the person I see in that story.

I’m not asking for forgiveness yet. I know I haven’t earned it. But I would like a chance to talk. Just the two of us. No pressure. No agenda.

If you’re willing.

Love, Mom.

I showed the letter to Grandpa and Dr. Rivera. Both raised the same question: Could my mother truly change? We didn’t know. But they also pointed out something important: this was the first time she’d taken responsibility for anything without immediately deflecting blame.

“People can change,” Grandpa said slowly. “I’ve seen it. Not everyone does, but some do. Janet always followed Arthur’s lead more than she led. Maybe she’s starting to find her own conscience.”

After some thought, I agreed to meet her at a coffee shop halfway between Elmhurst and Lincoln Heights. Neutral ground. Public enough that neither of us could retreat into old yelling patterns.

She arrived on time, wearing jeans and a simple sweater instead of realtor armor. For the first ten minutes, we talked about safe things: my leg, her garden, the weather.

“I joined a support group,” she said finally, fingers wrapped tight around her cup. “For parents estranged from their adult children.”

I blinked. “I didn’t know those existed.”

“Oh, there are more of us than you’d think,” she said, a bitter laugh escaping. “In those meetings, we tell our stories. Why our kids pulled away. What we think happened. Then other people… react.”

She stared into her coffee.

“Some of the stories I heard sounded a lot like ours,” she admitted. “Parents choosing work. Parents calling their kids dramatic. Parents insisting everything they did was for their children’s own good while ignoring what the children actually said. Listening to them, I kept thinking, ‘That’s awful. How could they do that?’ Then I realized I was doing the same things.”

It wasn’t a full apology. But it was closer than anything I’d gotten from her in twenty-five years.

“What about Dad?” I asked.

She sighed.

“He’s not ready,” she said. “He thinks you’ve been brainwashed. His pride won’t let him consider that he might have done anything wrong.”

“He tried to use my settlement as leverage,” I said. “It’s hard to come back from that.”

“I know,” she said quietly. “I’m not asking you to pretend any of that didn’t happen. I’m just asking if we can try to build something different. Slowly. On your terms.”

So we started small. Coffee once a month. Clear rules: no talk about my finances, no pressure to “let your father handle things,” no pretending the ER texts didn’t happen. Sometimes it was awkward. Sometimes it was surprisingly normal. Sometimes she slipped and started to say, “Your father says—” and then stopped herself.

“He doesn’t have to be in every room I’m in,” I told her once. “Not anymore.”

A year after the accident, my body bore the story in faint scars and a slight stiffness when the weather changed. But I could walk, run short distances, climb stairs if I had to. I signed up for a charity 5K, not to prove anything to anyone else, but to myself.

My career had shifted too. At Goldstein & Associates, I’d become the unofficial go-to for personal injury cases. My experience navigating hospital paperwork, insurance adjusters, and manipulative family members made me uniquely suited to help clients in similar situations.

“I know you didn’t ask for any of this,” Martin said when he promoted me to paralegal specialist, “but you’ve turned it into something that helps people. That’s not nothing.”

On weekends, I still drove out to Elmhurst to have dinner with Grandpa. Sometimes we ate at his house. Sometimes I brought him into the city and introduced him to new restaurants he’d never try on his own.

“You know,” he said one night as we sat on his porch swing, the sky pink and gold over the quiet street, “when your grandma died, I thought the worst thing that could happen to me had already happened.”

He looked over at me.

“I was wrong,” he said. “Watching you lying in that hospital bed, knowing my own son wouldn’t come… that was its own kind of heartbreak. But watching you stand up to them? Watching you build a life that looks nothing like theirs and everything like yours? That’s… healing I didn’t know I needed.”

I thought about the objects that had anchored this journey—the flag magnet in the ER, the teal journal, the battered Honda Civic, the blue folder that had separated my money from my parents’ grasp.

“I never thought something this terrible could give me something good,” I said. “I wouldn’t choose that crash. I wouldn’t wish it on anyone. But I can’t regret where it led me.”

“That’s the thing about the worst days,” Grandpa said. “They show you who you are. And who everyone else is, too.”

Now, when I open my bedroom closet, the blue folder sits on the top shelf next to that teal journal and a small desk-sized American flag Cassandra gave me as a joke after I completed my first 5K.

“Your own little finish-line flag,” she’d said.

The folder doesn’t scare me anymore. It reminds me of a hinge day when I chose myself. It reminds me that my parents’ reactions don’t define my reality. It reminds me I have the right to draw lines and enforce them.

I’ve shared my story in bits and pieces—around support-group circles, with clients who think they’re weak for considering boundaries, eventually in an online video where I told viewers, “If you’ve ever had to choose between your own safety and someone else’s comfort, you’re not alone.”

Some people hear it and say, “I can’t believe parents would act like that.” Others nod like they’ve lived it themselves. Both responses matter.

If you’re reading this and some part of it sounds familiar—if you’ve ever stared at your phone in a moment of crisis, hoping for a name to appear that never does, if you’ve ever watched someone try to turn your pain into their windfall—I want you to know something I learned at twenty-five in a hospital bed under a tiny flag magnet.

Your worth is not measured by how convenient you are to someone else’s schedule. Your safety is not negotiable. Your life is not their business plan.

Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is look at the people who taught you what “family” was supposed to mean and decide to define it differently. Sometimes the most loving thing you can do—for yourself, and even for them—is to set boundaries so clear and strong they might as well be printed and slipped into a navy-blue folder.

The accident that nearly ended my life gave me something I didn’t know I was missing: permission to live it on my own terms. To build a chosen family out of people who show up, not just people who share my last name. To understand that loyalty without respect isn’t loyalty at all.

If my story resonates with you, share it with someone who needs to hear that they’re not selfish for wanting to feel safe, seen, and valued. Tell them this: you are allowed to protect yourself. You are allowed to expect more than “Can’t this wait?” when you’re bleeding. You are allowed to open your own blue folder and sign your own name.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load