“Don’t embarrass us,” my mother hissed as we pushed through the courthouse doors, her pearls clicking together like teeth. “Just sit in the gallery and let the real lawyers handle this.”

I kept walking. My heels met the marble with a cadence I had built brick by brick over years nobody knew I was living. My father drifted alongside us without ever quite aligning, gaze fixed on a far corner of the ceiling like I was a stain he couldn’t scrub out.

We were in downtown Omaha, Douglas County, Nebraska, in a building that liked to remind you it would outlast your problems. Brass railings. Floors polished by a century of feet. The seal of the state set in tile at the landing where the hallway split like a wishbone toward two wings of courtrooms.

My name is Anna Thompson, and for most of my thirty-one years I have been the disappointment my parents pretended not to have. The dropout. The failure. The ghost they edited out of conversations at their country club. We were here because they wanted to evict a tenant. A woman named Clare Mitchell who had, in my mother’s words, “the audacity to stop paying rent over a little moisture.”

“A little moisture,” my mother had said into the phone two weeks ago, the word moist stretched like gum. She meant the black mold blooming above a girl’s bed. She meant a ceiling seam that leaked when it rained. She meant window frames swollen shut and a broken furnace cycling itself into carbon-scented limbo. She meant a building they’d inherited from my grandfather and ran like medieval fiefdom: taxes collected, complaints ignored.

“Just so you know,” she’d added, “your sister Melissa will be there because she understands loyalty.”

I hadn’t told her I planned to come. I hadn’t told her much of anything in twelve years. The last conversation we’d had that mattered ended with my father throwing my clothes onto the lawn and telling me I’d never amount to anything without them. I slept in my car for a while after that. I learned which grocery store lots stayed quiet past midnight. I learned how many minutes you could afford to close your eyes in a parked car and still get to your morning shift on time. I learned that vending machine crackers, if you eat them slowly, trick your body into believing in lunch.

Some truths you don’t say. You build them instead, semester by semester, job by job, ride by ride. You build them until one morning you wake up in a studio apartment shaped like possibility with a stack of casebooks and a part-time badge for the night shift at a hospital and a letter that says you passed the bar exam. You build them until the marble remembers how your heels sound.

We reached the courtroom. My mother set her hand on my elbow as if the gesture were affectionate instead of steering. “You will not speak,” she said under her breath. “You will not create a scene.”

I slid her hand off me without looking at her and pushed through the door.

The room smelled like paper and coffee. Rows of pew-style benches. Fluorescent lights gentled by ceiling height. At the defense table, a small woman in a thrift-store dress sat with her hands knotted in her lap. Clare. Her eyes were red-rimmed in the way that means someone has practiced not crying so long the vessels made permanent compromises.

My parents took their places at the plaintiff’s table with their attorney, a man named Gerald who charged five hundred dollars an hour to be sure nothing inconvenient touched their money. My mother turned and flicked her fingers toward the gallery. Sit. I walked past her shoulder, past the aisle, past the invisible line she believed divided her life from mine—and took the empty chair beside Clare.

“Excuse me,” I said softly. “I’m your attorney.”

Clare flinched as if the word could burn. “I—I can’t afford—”

“Consider this pro bono.” I set my briefcase down and pulled out a thin folder I’d assembled in the two weeks since Melissa’s offhand mention of the case cracked open a door in me. “I’ve reviewed everything. You have the right to withhold rent when an apartment is uninhabitable. Nebraska recognizes an implied warranty of habitability. We’ll walk the court through what that means.”

Behind us, a sharp intake of breath. My mother. The shape of fury has a sound when it’s trying to be polite.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?” my father whispered harshly, half-rising.

I turned and for the first time in twelve years met both their eyes without flinching. “My job.”

“You’re not a lawyer,” my mother said, color rising like a rash.

“Actually,” I said, sliding my bar card from my wallet and holding it up, “I am.”

The bailiff called the room to order. A side door opened. Judge Patricia Hullbrook took the bench with the economy of movement of someone who has no extra time to spend on false starts.

“All rise.” We rose. We sat.

The judge looked over the case list, then across the tables as if measuring them for a suit. Her gaze paused on me. Something in her expression shifted the way a room darkens when a cloud slides over the sun.

“Counsel,” she said, voice even, “approach.”

Gerald and I stepped forward. Up close, the judge’s steel-gray hair revealed strands stubbornly un-dyed at the temples, a betrayed vanity turned into authority. “I see the defendant is represented now,” she said. “Name for the record?”

“Anna Thompson, Your Honor.”

She tipped her head, eyes narrowing with a flicker that looked like memory. “Thompson.” A beat. “Didn’t you argue the Riverside Apartments case last year?”

“Yes, Your Honor.”

“You won it.” She didn’t ask. “Tenants got repairs and damages.”

“That’s correct.”

Her mouth flattened into something dangerously close to a smile. She glanced at Gerald, then back at me. “All right. Let’s proceed.” She leaned forward a hair—curiosity making the bench feel smaller—and under her breath, almost to herself, murmured, “Wait… is that her?” The court reporter froze, the bailiff’s pen stilled. Then the judge reset her face, and the room remembered to breathe again.

Gerald went first. He painted Clare as difficult, unreasonable, dramatic. The photographs he offered the court were years old, taken when fresh paint still pretended to be structural integrity. He used phrases like “minor maintenance issues” and “legally binding obligation to pay rent.” He said my parents were “responsible landlords”—the kind that kept receipts in manila envelopes and Christmas cards from tenants who moved on to homeownership.

When it was my turn, I walked to the evidence table and laid out new photographs: the ceiling stain like a spreading continent, the black flecks that dusted the girl’s headboard, the window that wouldn’t lock, the furnace with a carbon monoxide tag the color of a stop sign. I laid out maintenance requests, date-stamped and unanswered. I laid out the city inspector’s report that had done everything but draw a skull and crossbones in the margin.

“Your Honor,” I said, “the law doesn’t ask tenants to be martyrs. It asks landlords to keep homes fit for human beings. When they fail, tenants have remedies. Ms. Mitchell used one of the few she has.”

The judge read. Gerald objected exactly as often as a man like Gerald believes he should. Overruled. Sustained. Overruled again.

When I submitted the pediatrician’s note about Clare’s daughter’s new-onset wheezing, the judge’s jaw tightened. “Counsel,” she said to Gerald, “did your clients know about mold?”

“Some moisture,” he said. “They were aware of some moisture.”

“Did they know about mold?” The air thinned.

“Yes, Your Honor,” he conceded. “They dispute the severity.”

“The city doesn’t,” she said, tapping the inspector’s report. She looked at my parents—my mother with her pearls, my father with his tailored restraint—and something like disappointment dimmed her eyes. “Continue, Ms. Thompson.”

By the time I rested, there was no narrative left that made Clare the villain. There was only an old story about money and what it turns off in people when they let it.

The judge looked at my parents a long moment, then at me. “I’ve seen a lot of these disputes,” she said. “This one stands out.” She set her pen down with ceremony. “Eviction dismissed. Plaintiffs are ordered to complete repairs within thirty days to code and reimburse the defendant three months’ rent and medical expenses related to the child’s respiratory symptoms. If repairs are not completed as ordered, this court will refer to the city for further action.” She struck the gavel. A sound like a door closing behind a different life.

Clare covered her face and sobbed once in a way that made me think of an emptied-out house. I squeezed her hand. “Tell the truth when people ask,” I said quietly. “That’s your only job.”

In the aisle, my mother’s whisper had lost its polish. “How dare you.”

“I did my job,” I said.

“You humiliated us,” my father growled. “Your own family.”

“You stopped being my family,” I said, “the day you threw me out and told me I was nothing.” The words came without heat, like you say the weather out loud just to prove you exist in it.

We filed out. Reporters waited out on the steps like pigeons. I put a hand at Clare’s back and made space for her to pass. My parents stood on the landing arguing with Gerald under their breath, fury looking for an invoice.

At Kestrel & Associates, the converted warehouse that felt more like home than any place ever had, Diane Kestrel waited in the conference room. Exposed brick. A wall of secondhand law books that never quite lined up. Mismatched mugs that all somehow poured courage.

“Clare called,” Diane said when I walked in. She smiled without showing teeth, pride held close. “You did good work.”

“I presented facts.”

“You gave a woman her house back,” she said, and her tone made it sound like a sacrament. Then the smile thinned. “Anna, your parents aren’t going to let this go.”

“They’ll try to hurt me,” I said. “They don’t like to bleed in private.”

“They’ll go after your license if they can. They’ll feed the rumor mill. They’ll call people we know.” Diane folded her hands. “We’ll deal with it. But be ready. Cornered people make messy choices.”

I nodded. A knot I hadn’t admitted to loosened a little because someone said we out loud.

When my phone rang that evening from an unknown number, I almost didn’t answer. “Anna Thompson?” a man said. “My name is Henry Bradford. I was your grandfather’s attorney. We need to talk.”

The word grandfather felt like a drawer you open and find a sweater that still smells faintly like safety. “Now?” I asked.

“Tomorrow morning, if you can. Nine o’clock.” He gave me an address in an old building downtown that the city had built when elevators wanted to impress you.

I didn’t sleep much. The next morning I stepped into a corner office that smelled like oiled wood and paper. Henry Bradford rose from behind a desk that might have weighed half a car, his hair white, his eyes quick in a way age can’t teach you if you didn’t learn it young.

“Thank you for coming,” he said, offering his hand.

“You said it was urgent.”

“It is.” He reached into a drawer and set a thick file on the desk. “Your grandfather—James Thompson—made provisions for you I was not permitted to disclose until certain conditions were met.”

“What conditions?” My voice did the small embarrassing catch it does when hope bumps into habit.

“Turning thirty or obtaining a professional degree.” He pushed a document across to me. “You met both. The trust has accrued to just under sixty thousand.”

For a beat, numbers were a language I didn’t speak. Then the decimals resolved. Sixty. Thousand. Dollars. Loan balances re-dealt themselves in my head, lines of credit shrinking like shadows at noon.

“Why now?” I whispered.

“Because your grandfather loved you and knew your parents,” Henry said simply. “He didn’t want them to know. He feared they’d find a way to take it.”

He slid an envelope toward me next, seal still unbroken, my name in my grandfather’s careful engineer’s printing. Inside, a single page: Dear Anna, if you’re reading this, then you’ve done what I always knew you could. I’m proud of you. I tried to change my will to give you half. I ran out of time. Be careful. They love money more than people. Use this to build a life nobody can take. Love always, Grandpa.

“I have to tell you something else,” Henry said when I looked up, tears blurred into the kind of prism that makes rooms look braver. “The week before your grandfather died, your mother came to my office. She asked pointed questions about whether he’d amended his will. She was… insistent.”

A cold draft moved through me. “He died suddenly.”

“Heart failure,” Henry said. “But he’d just had a physical. His doctor told him he had the heart of a man twenty years younger.” He hesitated. “I cannot accuse anyone. I can tell you the timing always troubled me.”

I walked out of the building with the folder clutched to my chest and sat in my car while downtown went about pretending to be normal. The thing about suspicion is the way it rearranges memory. All the edges you didn’t know to trace suddenly align. I drove to the library and fed quarters into a scanner until my pockets were light and my file was heavy with copies of news clippings and death notices and a small letter to the editor from a retired physician named Dr. Russell Hayes.

He had written that he’d been surprised by his patient’s sudden death, that two days earlier he’d examined a man and found nothing that predicted it.

I called the number on the bottom of the letter. He answered on the third ring with a voice that still remembered charts.

“Dr. Hayes, my name is Anna Thompson. James Thompson was my grandfather.”

A pause that felt like a hallway you can hear someone walking down. “I remember James,” he said. “A good man.”

“You wrote that you were surprised by his death.”

“Are you asking as his granddaughter?” he asked gently. “Or as something else?”

“As an attorney who might need to understand whether a crime was buried with a certificate that said otherwise.”

“Elmwood Park,” he said at last. “By the pond. An hour.”

He was there with a paper bag of breadcrumbs, hands spotted with age and a carefulness that looked like contrition. Ducks trailed him like children.

“I’ve carried something too long,” he said without preface. “Two days before your grandfather died, he came to see me. Nausea. Dizziness. Tingling. I ordered tests. The results came back after he was gone.” He swallowed. “Elevated digoxin. He was not on heart medication.”

The world rearranged itself, and the pond looked suddenly theatrical, like it had been a stage waiting twelve years for the line where you name the play.

“Poison,” I said, and my mouth made the shape of the word before I believed I’d said it.

“Someone administered it,” he said. “Likely in small doses over days. Enough to induce arrhythmia. Enough to look like a heart that simply failed. I went to the police. They waved me away. The medical examiner had ruled natural causes.”

“Why didn’t you push?” My voice was steadier than I felt. Grief has a way of making you sound like you’re the adult in the room.

“Your father came to see me,” he said quietly, and the ducks drifted closer as if to eavesdrop. “He said an investigation would destroy your grandmother. He said the family wanted peace. He offered money. My wife had been diagnosed with cancer. I told myself I was doubtful enough to sleep. I took his money. I have not slept well since.”

“Would you swear to that?” I asked. “Will you sign it? Will you testify?”

“I will,” he said, lifting his face to the wind like a penitent turning toward rain. “I’m old enough not to lie to myself anymore.”

By dusk, I had a notarized statement. I took it to the Douglas County Attorney’s Office and sat across from Catherine Morris, a prosecutor with eyes like the kind of scales that don’t move unless you are sure.

“This is serious,” she said after reading. “And it’s old. Twelve years is a long time to hide a murder.”

“You need motive,” I said. “You need money.”

“We need more than suspicion and an elevated digoxin level,” she said. “Bank records. Purchases. Something that ties your parents to intent and method.”

I stared at the wall just over her shoulder where someone had hung a watercolor of a field to remind the room Nebraska was mostly sky. My mother kept everything. Receipts. Ledgers. Boxes labeled by year like an archivist of her own myth.

I called Melissa. She answered on the fourth ring, voice small like she was waiting to be told what to feel.

“Mom and Dad are furious,” she said. “They’re talking about suing you for defamation.”

“I need your help,” I said. “I think they killed Grandpa.”

Silence unrolled between us like a carpet nobody wanted to stand on. “What?” she whispered finally.

I told her about Henry. About the trust. About Dr. Hayes and the test result that made the coroner wrong. About the police who take the easy answer when the people who can afford to insist write checks big enough to look like gratitude.

“They wouldn’t,” she said. But her voice had started to wobble like a bridge that wasn’t built for this many cars.

“They would,” I said. “They did. I need the basement files. The ones Mom keeps by year. The months before he died. Bank statements. Credit cards. Pharmacy receipts. Anything that smells like debt or seeds or medicine no one should have.”

“I can’t go through their things,” she said reflexively, the way you say I can’t step off the path that raised me.

“You can,” I said. “Because if I’m right, those things are evidence of murder.”

Another long silence. Then: “I’ll look.”

The next evening we met in a coffee shop just far enough from our parents’ neighborhood to feel safe. Melissa looked like someone who had learned overnight that her house didn’t have a foundation.

She slid a folder to me across the table. “I found these,” she said. Her hands shook. “I shouldn’t have, but I did.”

Inside: bank statements with balances bled into the red. Credit cards maxed. A line item for cash advances. Three months of stress drawn in columns and negative signs. Receipts from a medical supply site. Two orders from an online seed retailer: digitalis purpurea—foxglove. I turned a page and there it was. A small spiral notebook. My mother’s handwriting, neat as a ruler.

I read. Jay says changing will. Half to Anna. Can’t let that happen. Will lose everything. Need to act fast. Research: digoxin—difficult to detect, naturally occurring. Tea every morning. Dosage? Calculate. The next page was math in my mother’s tidy hand. Another page: It’s done. Doctor called it heart failure. No one suspects. We’re safe. Properties are ours.

The room tilted. “Where did you find this?” I asked.

“In her desk,” Melissa whispered. “Bottom drawer. False bottom.”

“Will you swear to that?” I asked. “Will you say it in court? Will you say it’s her writing?”

Melissa’s eyes filled. “Yes,” she said. “I can’t pretend anymore.”

We went to the County Attorney. Catherine read. Something in her face hardened that wasn’t anger. It was the thing some people call justice before they’ve seen what it costs to buy it.

“We’ll move now,” she said. “Search warrants. Arrest warrants.” She looked at Melissa. “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be,” Melissa said, her voice a ghost learning to have bones. “He was our grandfather. He deserved better than two people who loved money more than they loved him.”

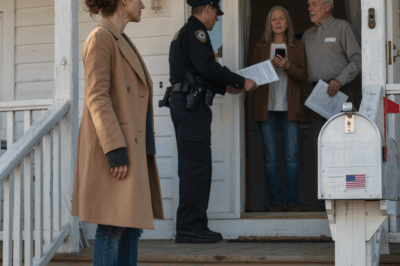

Two hours later we sat in a conference room watching a feed from a squad car dashcam as uniformed officers knocked on the front door of the house where I had once been a daughter until I wasn’t. My mother answered in her robe. For a second she looked like a woman invited to a party. Then the officer read the warrant, and her face changed to the thing people call truth when it finally refuses to be dressed. My father arrived in the background saying words to the officers that had worked on other people.

They did not work.

The news moved like news moves. My phone chewed through its battery vibrating against interviews and offers and the kind of congratulations that felt more like condolences. At the office, Kestrel’s ancient phones blinked until the buttons laughed. Former tenants called to say they had stories, too. A man named Thomas left a message that my father had once told him if he didn’t shut up about the furnace, he’d end up like James. “I thought he meant it as an example,” Thomas said when he came in to give a statement. “Now I think it was a confession.”

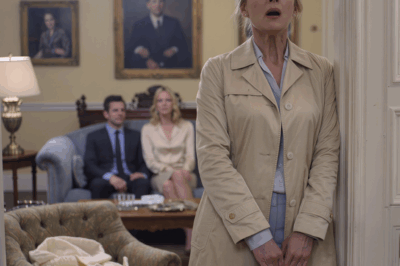

Six months later, my parents sat at the defense table in orange. Judge Hullbrook took the bench. Catherine tried the case for the State with a steadiness that made me want to stand every time she did. She called Dr. Hayes, who looked at the jury with eyes that didn’t ask for forgiveness, only permission to tell the truth finally. She called Henry Bradford. She called the handwriting expert who verified what everyone in that room already knew from the shape of my mother’s letters. She called Thomas.

When it was Melissa’s turn, she walked to the stand and swore and did not look away. “I found the notebook in our mother’s desk,” she said. “I found receipts. I found bank statements. I found proof.”

Frank—their lawyer, a man who looked like he had taken a case nobody else wanted—tried to build a defense out of character witnesses and the old trick men like my father reach for when the world refuses to behave: we are good people because we say we are. He put my mother on the stand to claim she’d been drafting a crime novel in longhand. The jury’s faces didn’t move.

I testified last. I told the story I had been telling myself for twelve years with different pronouns, different tenses, different verbs. I told it in the only tense the court understands—present—because truth, when you finally say it out loud, refuses to be past.

The jury took four hours. Guilty of first-degree murder. Guilty of evidence tampering. Guilty of fraud. The verdicts entered the room and rearranged the air as if the HVAC had finally been set correctly.

At sentencing, Judge Hullbrook looked at my parents the way you look at something you can’t quite believe you are still seeing. “You murdered your father,” she said. “You stole from your children the one person who believed the best about them. You chose greed over love so thoroughly that love started to look like a stranger to you.” She sentenced them to life without parole and added the years for the rest the way you add locks to a door.

Outside, microphones found my mouth. How do you feel seeing your parents sentenced to life? Relief, I said. Not joy. Relief that they can’t hurt anyone else. Will you accept the inheritance? No. Whatever the court can recover should be used to make people whole or as close to whole as money ever manages.

The court-appointed receiver liquidated what could be liquidated. Three properties. Two cars. The lake boat my father bought when my grandfather died. The proceeds, after fees and taxes, made a pool that felt both like something and not enough. Twenty-three former tenants sat in our conference room in chairs we’d borrowed from a church down the street, and I told them what the math could do for them—thirty thousand here, sixty there, more where medical records could draw lines between neglect and lungs.

A man in the back raised his hand. “You should keep some,” he said. “For doing this.”

“I didn’t do it for money,” I said. “I did it because we live under the same sky.”

Diane waited until the room emptied to pour coffee that tasted like old battles and say, very plainly, “I want you to make partner.”

I laughed because sometimes your first instinct is to make a joke of a thing that might change your life. “Are you serious?”

“I am,” she said. “I’m tired and you are exactly the kind of tired this work needs. You care and you fight and you remember hunger in ways that make you dangerous to the right people. That’s who should have their name on the glass.”

I told her I’d think about it. Then I walked to my car with the kind of lightness I mistrust and sat a minute to let my eyes adjust to a future that fit.

That night Melissa and I went to our grandfather’s grave. The stone was simple because James liked things that worked more than things that asked you to look at them. We brought violets because he grew them on the windowsill that faced the morning. Melissa knelt and touched the carved dates with two fingers like she was checking a pulse that had decided to keep time somewhere else.

“We got them,” she said softly. “It’s done.”

“I’m sorry it took so long,” I said. “I’m sorry you had to be the one to open the drawer.”

She nodded. “We were both the one,” she said. “Just in different rooms.”

We sat on the grass until the kind of dark that softens edges. On the way back to the car, Melissa slipped an envelope into my hand. “Henry gave me this,” she said. “He said Grandpa wanted you to have it when it was over.”

I read in the glow of the dashboard. You have already won, the letter said in a hand my brain remembered before my eyes did. The best revenge is living well as the person they said you could not be. Use your strength for people who don’t have enough yet. You are loved. You are enough.

Three months later, the restitution checks went out. Clare sent a photograph of her daughter standing in a dorm room with a paper pennant on the wall and a smile that looked like a construction project finished ahead of schedule. Thomas brought donuts and an invoice stamped PAID. The receptionist cried in the bathroom because some days goodness ambushes you.

Diane retired a year after that. I took the glass office because clients can find you faster if your name is where the light hits. Melissa, who had gone back to school for a paralegal certificate, took the desk outside my door. She kept pencils sharpened to a point I used to associate with nuns in movies, and she developed a way of asking “Are you sure you want to say it like that?” that saved me from two discovery fights and one avoidable apology.

People asked if I was angry still. Some mornings yes. Anger makes a good engine and a terrible map. But it fades when you’re busy building. It fades when your days are full of depositions and client meetings and afternoons at code enforcement hearings where you wear flats because there’s a lot of standing.

I didn’t marry. I didn’t not marry. I built a life with ten thousand small choices and some days that felt as holy as any vow. I bought a small house with a porch where geraniums made a pink line in summer. I kept a photograph of my grandfather on the mantel because some faces change the temperature of a room. On Sundays, Melissa came over with takeout and her laughter found the corners my house didn’t know were there.

Once, years later, she went to see our father. “For closure,” she said. “For curiosity.” She came back with a face that looked more relieved than anything else. “He doesn’t get it,” she said. “He thinks he was unlucky. That he got caught. Not that he was wrong.”

“Some people never say the part out loud that matters,” I said. “They don’t have the muscle for it.”

Our mother died of a stroke in prison. The call came on a Tuesday when I was drafting a motion to compel and eating almonds one at a time. I set the phone down and stared at the ceiling until the feeling found a word. It wasn’t grief, not exactly. It was a quiet I didn’t trust yet.

We set up a fund at the firm in my grandfather’s name. It paid filing fees for tenants who needed leverage and bought inhalers for kids whose apartments still hadn’t learned how not to make them wheeze. Every December we posted a list of donors on the wall and put a violet beneath it.

When the courthouse steps made the news again for something else, a reporter once asked me if I believed in cycles. “I believe in choices,” I said. “And in people who hold doors open long enough for other people to walk through.”

Sometimes, late at night in my office with the city moving outside like a living thing, I take out the two letters that built a bridge between a granddaughter and a future she wasn’t supposed to touch. I read the line about the best revenge and the line about being already enough, and I remember the day a judge leaned forward and the room stopped breathing because a story was about to admit it had been telling itself wrong. I remember a woman in pearls choosing a poison and a girl in a thrift-store dress choosing to withhold rent until somebody fixed the roof. I remember ducks on a pond turning their heads to listen to a confession the wind had been trying to deliver me for twelve years.

I remember my heels on marble. I remember the exact weight of a bar card in my fingers. I remember the feel of my sister’s hand palm to palm outside a courtroom where a gavel made a sound like a rescue.

People like to imagine justice arrives with trumpets. Most days it shows up looking like paperwork and patience. But sometimes—sometimes—it leans forward and says, Wait… is that her? and everyone in the room learns how to breathe again the way humans are supposed to when the truth finally fits.

I built a life from nothing, then used it like a lever. I kept a promise to a man who believed me when nobody else could afford to. I kept another to a woman who only wanted a safe room for her daughter to sleep. I am not special in the way stories want their heroines to be. I am ordinary in the way survival teaches you to be—efficient, stubborn, incapable of pretending I didn’t see what I saw. It turns out that’s enough. It turns out enough, repeated daily, becomes a kind of power.

Once, years after the trial, a young attorney fresh out of law school stood in my doorway with a folder clutched like a flotation device. “Ms. Thompson,” she said. “I don’t know if I’m cut out for this. People yell. Judges glare. Opposing counsel sneers. Clients cry. I go home buzzing like a loose wire.”

“Me too,” I said. “On the good days.” I told her the trick I learned in a grocery store parking lot: count to a hundred slow before you decide the next thing. Eat something even if it’s crackers. Keep building.

She laughed in that exhausted new-lawyer way that lights a match in your chest. “Did you always know?” she asked. “That you would be who you are?”

“No,” I said. “But someone did. And I decided to believe him.”

On spring mornings when the courthouse lawn goes green like an overnight confession, I park a block away and walk. The building is still older than my problems. The brass still holds fingerprints belonging to people who learned to tell the truth in rooms like this. The seal in tile still waits at the landing like a coin you flip when you’re brave. And every time I push through those doors and feel the cool air climb my arms, I hear my mother’s first words in this story—Don’t embarrass us—and think, Not today. Not anymore.

I take my seat. I open a folder. I say, “Good morning, Your Honor,” and watch a hundred small levers move because the law, at its best, is a system that turns ordinary insistence into something like grace. And if, every so often, a judge leans forward with recognition, if a room goes quiet to make room for a story that finally found its voice, I breathe with it. I let it count the beats. Then I begin.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load