The invitation arrived on cream-colored card stock with gold-embossed lettering, the kind of paper that makes a sound when you set it down. “An elegant evening,” it proclaimed in a confident, looping script, followed by the venue address: the Metropolitan Club downtown—one of the city’s most exclusive private dining establishments. At the bottom, in smaller print that pretended to be polite, it added, “Black Tie requested.”

I held the card between my fingers and let the edges bite into my skin—a small, clean pain that kept me from rolling my eyes at the flourish. The Metropolitan Club. Black tie. The sort of night where the band plays songs that make men tap two fingers on linen napkins and women pretend their shoes don’t hurt. Eight months since I’d seen them, and the paper pretended that fact was a mere scheduling quirk. It wasn’t. Eight months was a perimeter I’d built after the last dinner at Dad and Victoria’s house, the one where the conversation had skated along appetizers until David, elbows on reclaimed oak, looked up with an easy grin and asked why I “never chipped in” for the kind of family moments that apparently required invoices.

What I remember most from that night wasn’t his tone but the choreography: Victoria refilling Dad’s glass with a flourish that felt like a cue, Jessica taking an exaggerated interest in a charcuterie board she hadn’t paid for, Dad adjusting his cufflinks as if the answer might be in there somewhere. I had shown up with flowers and a dessert and a willingness to pretend we were a single unit. By the time the roasted salmon hit the table, the temperature of the room had been set to ‘gentle judgment.’ And when I said, lightly, that I’d be happy to pick up the check next time, Victoria made a small moue, a smile without the smile, and said there was no need for theatrics. The word calcified in the room. Theatrics. As though any gesture of mine was a performance meant to steal a spotlight rather than to give grace. I left early. I learned to bring smaller flowers.

That was the last time I put my ambition on the table with the flatware. Since then I’d let them assume. It cost less.

The invitation, though—this thing with weight and gilding—wasn’t casual. It was a promise and a dare. A signal that the evening would be measured not just in courses but in appearances. And appearances, I knew, were Victoria’s native tongue. She spoke it like a first language. I understood enough to answer in short sentences.

I stared at it for a long minute, the weight of eight months pressing at the base of my throat. Eight months since I’d seen my family. Eight months since that last dinner at Dad’s house, when my stepmother, Victoria, stacked her comments like fine bone china: delicate, expensive, and meant to cut if mishandled. Eight months since my half-brother David asked, in front of everyone, why I never seemed to “contribute” to family events—contribute, as though I’d been skimming off some communal fund rather than showing up with a smile and leaving with a headache.

The truth was complicated on purpose. I’d made it that way. After Dad remarried five years ago, I learned quickly that life was smoother if I wore gray instead of color. If I arrived late, left early, and folded myself into convenient shapes. Victoria came with three adult children who slid into Dad’s world with the frictionless ease of pearls on satin: charity galas, country clubs, ovens that had never seen a casserole dish but looked perfect in photos. David, twenty-eight, in marketing and perpetually networking; Jessica, twenty-six, between jobs so frequently that “between” started to sound like a destination; and Michael, twenty-four, still in graduate school and sure it made him interesting. They were practiced at appearing.

I was practiced at disappearing.

You don’t launch a crisis-management firm alone unless you’re comfortable being the quietest person in the loudest room. The first year of Mitchell Consulting was red-eye flights and loaner conference rooms that smelled faintly of old coffee and new carpet. It was a rental laptop that whirred when I opened models with too many tabs, a borrowed printer that misbehaved when the stakes were highest, and a wardrobe calibrated for credibility rather than compliments. I learned to sleep in the cold light of airports, to speak in bullet points without sounding like a bullet, to make a problem smaller just by standing near it.

The second year was a war fought on two fronts: deliver work that put out fires, and build a reputation that meant I’d be called before the match was struck. I stopped saying yes to everything. I started charging what the outcomes were worth, not what my imposter syndrome thought I could get away with. A CFO once told me, after we threaded a multi-billion-dollar recall without a fatal headline, that I had the temperament of a very expensive anesthesiologist. I took it as the compliment he meant and adjusted my rates accordingly.

By year three, when Meridian Industries lit up my phone at 3:12 a.m., I had an ops lead, a skeleton crew of analysts, and a conviction that speed is a form of kindness. We landed the crisis not because we found a brilliant fix in an archive no one had opened, but because we insisted on the unglamorous: verify, align, decide. A news cycle that could have eaten them alive passed like a storm that rattled windows and spared foundations. The CEO cried. I raised my prices again.

I never told my family any of this. Not because I was ashamed, but because they were uninterested in the mechanics of competence unless it arrived in a form they knew how to clap for. At home, outcomes were measured in front-row seats and named tables at gala dinners, in photos where the light hit your face just right. I built a company whose product was invisible when it worked. You don’t frame that. You sleep better, and you go back to work.

What they didn’t know, because I had stopped telling them, was that my work had gone supernova the same year Victoria ordered custom stationery with the family name embossed across the top. I ran Mitchell Consulting, a boutique crisis-management firm that quietly handled disasters for Fortune 500 companies. What began as a one-person shop five years ago had become a $200 million operation with offices in twelve cities and a client list that could pass for an index of the Dow. My fees reflected something simple and unfashionable at home: value. Fifty thousand dollars a week for executive-level consulting, more when the situation was on fire.

I learned to button that truth under a cardigan. The few times I’d mentioned a win, Victoria had located a more interesting anecdote about her daughter’s “creative pivot” or her son’s “mentor luncheon.” When I bought my first Porsche three years ago, she crinkled her nose and murmured something about overcompensation. When I closed on a penthouse overlooking the river, she wondered aloud how a “consultant salary” could support such extravagance. I stopped sharing. I dressed down for family events, drove my older Honda, and let them assume what they wanted to assume. If Victoria required a hierarchy to feel safe, I learned to give her one that cost me nothing but pride.

I accepted the invitation to Mom’s sixtieth because it wasn’t at the house.

Mom’s birthdays, before the remarriage and the choreography, had been messy on purpose. Sheet cake from a bakery where they knew her order, candles that bent in the middle because they’d been stored in a warm drawer, music that drifted in from a radio in the next room rather than being curated by a hired hand. I remember being small and standing on a chair to string crepe paper while she laughed at a joke I didn’t understand yet. Later, when Dad moved into the glass-and-granite chapter of his life, those parties migrated too. The last time Dad and Victoria hosted for Mom, the kitchen island had more square footage than my first apartment and the centerpiece looked like a hedge trying to assimilate. The night had been fine and off, like a smile with a wrong note in it.

The Metropolitan Club—neutral territory dressed up as exclusivity—seemed like a safer bet. At least there, politeness would be a house rule rather than my job alone. I planned accordingly. I chose the simple black dress instead of the one that read as a press release. I polished the modest heels I could stand in for hours if needed. I wrapped the freshwater pearls myself because it mattered to me that Mom’s gift had been touched by more than a card on file. And I took the Honda, not because I needed to hide, but because there is power in walking into a room on purpose rather than being delivered to it like news. The Metropolitan Club was a statement. It meant place settings and seating charts, valet tickets and champagne coupes that made everything taste like celebration. It meant the rules would be written down somewhere, which—ironically—made me feel less at risk.

The evening arrived damp and unseasonably warm. The club’s canopied entry glowed against the city’s glass-and-steel dusk; the valet stand teemed with tuxedos and low murmur. I pulled up in the Honda Civic I’d been driving to family functions for three years. The attendant was polite, puzzled, and ultimately practical. “Valet’s full, ma’am. Street parking two blocks down is usually open.”

Two blocks later, I walked back in a simple black dress and modest heels, carrying a small gift bag with a strand of hand-picked freshwater pearls for Mom. Inside, the private dining room was already humming. Crystal chandeliers drenched the room in honeyed light; round tables wore white linens and centerpieces so spare they were practically statements. Servers in crisp black-and-white moved like a practiced chorus.

I found my family in one sweeping glance.

It’s funny what the eye lands on when you think you know everyone in the frame. Dad’s tuxedo sat on him like a decision he’d made a long time ago and never revisited. He looked comfortable being important, which is different than being comfortable. Victoria wore emerald the way some women wear red lipstick: as both invitation and warning. It was the exact shade of money in movies, and the neckline said she trusted tailors more than gravity. Mom, soft silver and genuine delight, shone in a way that made me remember the first time she took me to a museum and told me it was okay to like the painting everyone else walked past. David worked the room with a smile that had been focus-grouped by his mirror. Jessica had perfected the art of looking like a solution without yet being attached to a problem. Michael held himself with the faintly apologetic posture of a man who has not yet converted the promise of higher education into the currency of anecdotes.

They were beautiful in the way a catalog is beautiful: clean lines, careful light, an invitation to imagine yourself wearing what you cannot afford. And I—out of habit more than strategy—floated along the edges until I reached the point of the night that felt like mine: Mom’s cheek, my “Happy birthday,” the small intimacy of giving her something I had chosen without committee. Dad at the head table, dignified in a tuxedo, expounding on some point to a man who nodded as though he’d been rehearsing it. Victoria beside him in an emerald gown cut to flatter ambition, accepting compliments that sounded like IOUs. Mom sat on Dad’s other side, silver dress catching the chandelier’s breath, her face open and happy in a way that made my chest lift. David, Jessica, and Michael were already circulating—easy laughs, practiced angles.

I went straight to Mom. “Happy birthday,” I said, bending to kiss her cheek and set the gift beside her plate. “You look beautiful.”

“Oh, sweetheart.” She squeezed my hand with both of hers. “I’m so glad you came. Look at you—elegant and understated. That’s exactly the look tonight.”

“Thank you for inviting me,” I said. And then Victoria’s perfume arrived a second before she did.

“Isabella, darling,” she cooed, the word darling shaped like an appointment you were expected to confirm. She air-kissed in that way that takes care to miss. “You made it. Wonderful.”

“Of course,” I said.

Her smile held. “I’ve arranged for you to sit with the service staff in the kitchen.” She said it lightly, like offering me the window seat on a short flight. “You understand? It’s about appearances.” The phrase was a soft pat on the wrist. “This is such an important evening for your mother, and we want everything to be perfect.”

For a beat, I thought I’d misheard. “In the kitchen?”

There are words that ring like flatware when they hit the air. Kitchen did that. Not because kitchens are lesser—most of my favorite conversations have happened in them—but because of the way she used it: as a category, a border. I remembered being thirteen and being told to “help in the back” when Dad’s partners came to the house, the way the command had been wrapped in praise for my helpfulness. I remembered the year I came home from college with a scholarship and a plan and was seated at the card table while Victoria’s children took the dining room chairs because they had guests. I remembered learning to let it slide off me, because friction leaves marks and I was tired of polishing them out.

I looked at Victoria’s face, all pleasant surfaces, and thought, Not tonight. But I smiled anyway, for Mom’s sake, for mine, because sometimes the only power you have is the timing of when you tell the truth.

“Well, you know how these things work,” Victoria said, her tone honeyed and steady, eyes cool. “The main dining room is for family and close friends. The kitchen is much more comfortable—less formal, more relaxed. You’ll love it.” Her eyebrows flicked, the universal sign for be reasonable.

I let my eyes travel the room, not for effect but to be certain. I recognized Dad’s law partners, two of Victoria’s book club friends who only read the title page, and a whole crescent of country-club acquaintances—a winter garden of seasonal blondes and navy blazers. “Victoria,” I said quietly. “I am family.”

“Of course you are, sweetie. But you understand the social dynamics here.” She pivoted a smile toward a couple gliding past as if to prove she had them at her fingertips. “This isn’t like our casual dinners.”

Dad was deep in conversation. Mom, still opening gifts, hadn’t heard a syllable. I began, “I don’t think—”

“I’ve put a tremendous amount of work into this evening,” she cut in, still smiling, a sharper edge now threaded through her voice. “Please be understanding.”

“Excuse me,” a server said, hesitant, appearing with the timing of a stage cue. “Are you Miss Isabella? Mrs. Morrison asked me to show you your dining arrangement.”

Victoria tilted her head encouragingly. “Go ahead, darling. You’ll be much more comfortable.”

The path to the kitchen ran past the bar—where David was building a story and an audience—and along windows that framed the city like a painting the club had purchased to show it had taste. Behind the swinging door, the world sharpened: the percussion line of pans, the spun-sugar hiss of service, clipped orders shaped by a chef who spoke with his whole body. In one corner, a small round table had been set with basic place settings, institutional flatware, and a view of the expo line.

“Mrs. Morrison thought you might prefer to dine here,” the server said, clearly uncomfortable with both the errand and the euphemism. “Less formal atmosphere.”

I sat.

Heat like a held breath lifted off the sauté line. The room smelled faintly of citrus and butter and the iron note of seared protein. Tickets flapped on their metal bar like prayer flags, each one an ask waiting to be answered. A runner slid past with a tray of soups that trembled but did not spill; another returned with plates that were too empty, a server’s apology shaped as speed. The dishwasher sang a rhythm that kept everything honest.

Someone set water at my elbow without asking. A woman in chef whites, sleeves pushed to her elbows, gave me the quick scan restaurant people reserve for variables: Will this complicate service? I shook my head. She ghosted a smile that acknowledged both the absurdity and my effort not to make it worse. A moment later, the salmon arrived—perfectly cooked, resting on a bed of something herb-bright and expensive—on a plate that belonged to the break table, not the dining room. I noticed the absence of the gold rim the way you notice a tan line in winter. It wasn’t the plate’s fault. It did its job.

The kitchen has its own manners. Eyes meet when hands are full, space is shared like language, please and behind you matter more than please and thank you. When the sous‑chef asked if I was staff, it wasn’t a challenge. It was inventory. I told him the truth in a quiet voice that didn’t ask for an audience. He gave me a nod that contained a whole paragraph: I see you. I can’t fix the room you came from. I’ll make sure the food is hot. The kitchen staff registered me with brief, professional curiosity, the kind you offer an actor who’s stumbled into the wrong rehearsal. Someone set down the salmon entrée plated on plain white china instead of the club’s gold-rimmed pattern. A sous-chef paused during a lull, pushed his cap back, and asked, “You staff?”

“I’m the birthday woman’s daughter,” I said.

His eyebrows rose. He nodded once and said nothing—an economy of decency that landed like a blessing. I ate quietly, the room around me conducting the party I was not invited to attend. Laughter from the main room arrived as a muffled ribbon under the steady clatter of service.

Halfway through the entrée, my phone buzzed.

Blackstone. Half a million a week for twelve weeks, if we landed it the way they wanted. Numbers big enough to feel theoretical even to people who work with numbers for a living. I did the math without trying: five weeks in, the project would have paid for every college tuition, every wedding, every mortgage I’d ever been told I didn’t contribute to—three times over. The thought didn’t make me smug. It made me tired. The currency of belonging in that dining room wasn’t denominated in dollars. It was minted in deference.

Confirm, I typed. Then: Have the Phantom meet me here at 9:30. It was a petty choice only if you believed visibility was pettiness. I believed, in that moment, in a different definition: sometimes clarity needs a vehicle. Marcus, my assistant: Blackstone has agreed to your terms. They’re offering $500,000 per week for the three-month restructuring. Confirm?

I stared at the number the way you might stare at the ocean—immense, impersonal, familiar. My thumbs moved without heat. Confirm. Also, have the Phantom meet me at the Metropolitan Club at 9:30 p.m.

The Phantom, ma’am? Not the usual vehicle?

The Phantom. Thank you.

I finished my dinner and sat a moment longer, letting the details file into their labeled places. This wasn’t about etiquette. It wasn’t even about tables. It was about choreography. Victoria wanted me edited out of the shot, and she had chosen the quickest way to communicate it to every guest with eyes: sequester the inconvenient woman in the kitchen and call it comfort. It was efficient and demeaning, and she assumed—based on years of evidence—that I would oblige.

At 9:25, I stood and smoothed my dress. The kitchen crew, all professionalism, asked if I needed anything else. I thanked them—meant it—and pushed back through the swinging doors into the curated hum of the dining room.

The party had found its rhythm.

The string quartet in the corner had switched from competent classics to the kind of upbeat arrangement that signals a room it may start to loosen its jaw. A woman in navy laughed a shade too loudly, chasing her own echo. A man in patent leather told a story with both hands, the way men do when they want their certainty to be contagious. Mom glowed, not from the compliments but from the attention paid to the people she loved. Victoria glided with the efficiency of a maître d’, dispensing warmth like favors. And I—threading through the space to say goodnight—felt like a person who had learned to take up exactly as much room as a rumor and no more.

“Leaving so soon?” she asked, arriving on cue. I admired, in a distant way, how good she was at timing. Some people weaponize words. She preferred the precise placement of sugar. It has the same effect, if you do it right. Guests were drifting between tables, sparkling around the edges of conversations with flutes in hand. I moved directly to Mom, who was caught in a constellation of well-wishers admiring the neat galaxy of gifts clustered at her elbow.

“Mom,” I said, touching her arm. “I need to head out soon. Thank you for a lovely evening.”

“Oh, but darling, we haven’t even had cake,” she protested, her mouth turning down like it wanted to keep the night unbroken.

“I know. Early morning,” I said.

Victoria materialized as though my name had been a password. “Leaving so soon?” Her voice carried just enough to be overheard. “But you barely had time to experience the party atmosphere.”

“I’ve experienced enough,” I said.

“Well,” she continued, bright and brittle, “I hope the kitchen arrangements were comfortable. I thought they’d be more your style.” A few nearby conversations stalled mid-sentence. Mrs. Patterson, one of Mom’s oldest friends—soft-voiced, steel-spined—turned. “The kitchen?” she repeated. “What do you mean?”

Before Victoria could stage-manage an answer, my phone chimed again. Marcus: The Phantom is arriving now, ma’am.

The club’s front windows stretched like a movie screen along the room’s far wall. Through them, a sleek black Rolls‑Royce Phantom glided to a stop at the curb, evening light washing its perfect surfaces in a way that made every head turn. The valets snapped to attention as if choreographed by a director who cared about servility as art. My driver stepped out in a tailored chauffeur’s uniform and rounded to the rear door, waiting.

“That’s my ride,” I said.

Sound behaves strangely in rooms like that. The gasp wasn’t audible so much as felt, a pulling back of air that left a crisp edge around everything. Through the glass, the Phantom looked like it had been carved from the same night the city was wearing. The valets straightened as if their spines remembered finishing school. Someone near the windows said, “Good Lord,” and then recovered their inside voice.

Dad moved toward the view the way a man moves toward a fact he hasn’t decided whether to argue with. David announced the make like a game-show host who’d been handed an answer card. One of Dad’s partners calibrated the number because men like him collect numbers the way children collect glossy cards: proof of knowledge, proof of membership. Victoria’s face did a quick slide from victory to vertigo. In that half second, I saw her do the math I had refused to do for her for five years.

“Yours?” she asked, and because the theater of the room demanded it, I let my answer be simple. The truth doesn’t need decoration. It needs volume.

Dad appeared beside me as though the gravity of the car had pulled him in. “Is that—?” he began.

“A Rolls‑Royce Phantom,” David provided, voice edging toward awe. “That’s like a five-hundred-thousand-dollar car.”

“More,” one of Dad’s partners said, arriving with authority born of habit. “Latest model. Closer to six hundred.”

Victoria’s face blanched. “Isabella,” she managed, “whose car is that?”

“Mine,” I said. Calm was easy when the facts were simple.

The room took a breath. “Yours?” Victoria’s voice was a thread.

“Marcus has been my driver for two years,” I said to the space, because there was no point whispering. “I usually have him pick me up in something modest for family events. Tonight felt like an exception.”

Mrs. Patterson blinked and leaned in with new interest. “Your driver? Isabella, what is it you do?”

“I run Mitchell Consulting,” I said. “We manage crisis and restructuring for Fortune 500 companies.”

Dad’s law partner pointed, recognition lighting his face. “Mitchell Consulting—holy—excuse me, ladies. You handled Meridian Industries last year. Brilliant work.” He looked at Victoria, then back to me as if recalibrating a map. “Your firm charges—what is it—fifty thousand a week?”

“Our rates vary by project,” I said. The line fit like a well-tailored suit.

His grin widened, then faltered as he felt the tilt of the room. “Well,” he said, chuckling to cover his retreat, “either way, impressive.”

I kissed Mom’s cheek. “Happy birthday, Mom. I hope the rest of your evening is wonderful.”

Her hand tightened around mine for a heartbeat. “Drive safe,” she said, in the voice that has followed me out of rooms since I had car keys. It contained more apology than the night allowed. I squeezed back, letting the squeeze mean what language could not hold in that room: I see you. I’m okay. We will talk when the lights are less expensive.

Conversations began again in the wake of the Phantom’s quiet arrival, this time quick and breathy. Did you know? No idea. In the kitchen? That’s—

At the door, I turned back. Victoria stood rigid beside Dad, a tableau of shock framed in chandeliers. “Oh, and Victoria,” I said, comfortably across the space. “Thank you for the dinner arrangement. It was very illuminating.”

I stepped into the cool evening and let the quiet fold around me like something I’d paid for. “Good evening, Miss Mitchell,” my driver said, holding the door. “I trust your night was satisfactory.”

“Educational,” I answered, sliding into the Phantom’s back seat. As we pulled away from the curb, I saw faces temporarily framed in glass—curiosity, calculation, faint disapproval searching for a home.

By the time I reached my building, my phone had become a small orchestra.

My penthouse is the opposite of a club dining room: quiet on purpose, defined by windows that don’t need drapes to feel finished, a kitchen that has earned the burn marks on its handles and the scratches on its cutting boards. I toed off my heels, poured wine into a glass that didn’t match the others because perfection makes me nervous, and let the city be a map at my feet. The Phantom’s departure had been noiseless in the way money often is. The living was done in decibels: the dishwasher’s hum, the ice settling in the freezer, the small relief of a zipper unteethed.

I didn’t check the messages. Not yet. The calls would sort themselves into predictable piles: defense, curiosity, apology, logistics. I’ve built an entire career on the idea that you should never respond to a crisis just because the crisis wants you to. You respond when your response will land. I let the night tilt toward morning and made a list that wasn’t a list: new charity commitments I actually believed in, clients to say yes to, a few personal policies to write in ink instead of pencil. The first one was simple: I would stop making myself smaller to fit a table that had been cut to someone else’s measurements. Missed calls and messages stacked like sheet music. I poured a glass of wine and set the phone face down. The river was ink and lights below me. I could taste something new in my mouth. Not victory. Not even vindication. Just the clean tracing of a boundary I should have drawn years ago.

Morning measured itself out in coffee and sunlight and the steady ping of attention. When I finally checked my phone, I found what I expected and what I didn’t. Dad: Isabella, we need to talk immediately. Victoria: There’s been a terrible misunderstanding. Mom: Sweetheart, please call me back. David: Why didn’t you tell us about your business? Jessica: OMG the photos from last night are all over Instagram.

I opened Instagram and typed “Metropolitan Club.” The top post was a shot of the Phantom taken from inside the dining room, the photographer framed by a crowd at the window. The caption read: When your ride arrives at the MetClub. #luxurygoals. Comments braided under it. Whose car? Someone from the Morrison party. Isabella Mitchell from Mitchell Consulting. Wait—the Mitchell Consulting? She was eating in the kitchen? Why would a daughter be in the kitchen? Family drama. That’s so messed up.

Sometimes social media picked the right villain without asking for context.

At ten, my assistant called. “I’m getting about fifteen interview requests this morning,” Marcus said, unruffled. “Apparently there’s a social-media story about you attending a party.”

“Decline all interviews,” I said. “If a statement’s needed, use this: Mitchell values family privacy and won’t be commenting on personal matters. And Marcus?”

“Yes.”

“Anything on the client side?”

“Three new inquiries,” he said, a smile I could hear. “All Fortune 100. Each asked for you by name.”

I laughed, not because it was funny but because it was absurd. “Crisis manager arrives in a Rolls‑Royce—who knew it worked as marketing?”

“Apparently it conveys ‘competent in a crisis,’” Marcus said. “Or at least ‘arrives on time.’”

An hour later, Dad called again. I answered.

He started with my name the way men do when they’re trying to soften the ask. “Isabella.” A pause to let me enter the conversation his way. “We need to discuss last night.” He said discuss like it could be managed by an agenda and adjourned after coffee.

“What would you like to discuss?” I asked, not offering him an easy exit.

“You embarrassed Victoria,” he said, choosing the frame that made him feel least complicit. “In front of our friends.”

“Did I?” I kept my voice even. “Or did the fact embarrass itself?”

“You know what I mean.” The sigh, the throat clear, the old habits putting on their shoes. “Making a scene. The car.”

“The car is a door with wheels,” I said. “It doesn’t make scenes. People do.”

Silence. I could picture him standing in his office, the city behind him like a certificate. “She says she thought you’d be more comfortable somewhere quieter,” he offered, moving to the rationale he could say out loud without tasting the acid on the back of his tongue.

“Dad,” I said, gentle because the truth was going to bruise anyway, “she seated me in the kitchen at Mom’s birthday party ‘because of appearances.’ I know what that means. You do too.”

The quiet stretched long enough to be honest. When he spoke again, the pitch had dropped. “I didn’t realize.”

“Where did you think I was?” I asked. “Did you notice I wasn’t at any table?”

He let out a breath that sounded like defeat and stubbornness taking turns. “She’s my wife,” he said finally. “I need to support her.”

“And I’m your daughter,” I said. “If support requires you to pretend humiliation is a misunderstanding, then you need a different definition.”

“I don’t want a rift,” he said, and there it was—the word that had been used to justify so much quiet complicity in our family. The avoidance of rifts had created canyons.

“Neither do I,” I said. “So here’s the bridge: acknowledge it was wrong. Make sure it doesn’t happen again. Treat me like family in rooms where it matters. I’m not asking for a spotlight. I’m asking for a chair.”

He didn’t have an answer ready, which was the first honest thing he’d offered all morning. “I’ll talk to Victoria,” he said at last, a sentence that can do either nothing or everything depending on who says it and why.

“Isabella, we need to discuss last night.” His voice had the tightness of a man trained to negotiate everything except family.

“What would you like to discuss?”

“You embarrassed Victoria in front of our friends.”

“Did I? How?” I swallowed a mouthful of coffee. “By correcting the seating arrangement? By leaving when I wasn’t welcome? Or by getting into my own car?”

“You know what I mean,” he said, lowering his voice even though he was alone. “Making a scene about the arrangements. Showing off with that car.”

“Dad,” I said, steady, “Victoria seated me in the kitchen with the service staff at Mom’s birthday party because, quote, it was about appearances.”

Silence. The kind you could set a glass on.

“I had no idea she did that,” he said finally.

“Where did you think I was during dinner? Did you notice I wasn’t at any of the tables?”

More quiet. “Victoria is very upset,” he tried again. “She says she thought you’d be more comfortable. Quieter. Less formal.”

“Stop,” I said. “We both know what happened. She wanted me offstage.”

“She’s my wife,” he said, soft with plea. “I need to support her.”

“And I’m your daughter,” I answered. “Apparently that comes second to supporting the person who humiliated me in front of fifty people.” I exhaled. “I’m done pretending this is acceptable to keep the peace. I’m done dressing my success in modesty so she can feel tall. And I’m definitely done being treated like the help at family events.”

“What do you want me to do?” he asked, not because he didn’t know but because saying it aloud would cost him.

“I want acknowledgment that what happened was wrong,” I said. “I want Victoria to understand that I’m not the struggling single woman she’s decided I am. And I want to be treated like family at family events. Not a problem to solve. If we can’t agree on that, I’ll continue building a life with people who value me as I am.”

I ended the call before he could negotiate the terms of my dignity.

Three days later, Mom called.

She skipped hello in the way mothers do when concern has made them efficient. “I’m sorry,” she said, and I could hear that she meant it, which is rarer than you’d think. “I didn’t know. I would have never—”

“I know,” I said, and I did. “If you had known, there would have been cake on plates and me in a chair next to you.”

She drew in a breath that snagged. “I’m thinking about other times,” she said. “When you left early. When you seemed… not yourself. I’m angry that I didn’t ask better questions.”

“Mom,” I said, “this didn’t start with you and it won’t end with one phone call. But it helps that you see it.”

“I want you at my table,” she said. “Always.”

“You’ll have me,” I said. “And I’ll have you.” We let the quiet sit for a moment, comfortable where the other quiets hadn’t been. “Isabella, sweetheart,” she said, skipping hello to land on the part that mattered. “I need to apologize.”

“For what, Mom?”

“I had no idea what Victoria did,” she said, the words quick with anger—a new color on her. “People asked me at the party why you were in the kitchen, and I thought you’d chosen it. If I had known, I would have put a stop to it. You’re my daughter.” She took a breath. “And I’m thinking about other times. When you seemed distant. Or left early. I’m wondering what I didn’t see.”

“Mom,” I said, the tight spot in my chest loosening a fraction, “I’m having lunch with Victoria tomorrow. It’s time we discuss how family is treated in this family.”

Two weeks later, another cream card arrived—this one for Dad and Victoria’s anniversary.

The calligraphy had the same professionally confident slant. Cocktail attire. The date, the time, the place. And under it, in Victoria’s hand: Looking forward to celebrating with the whole family. The sentence sat on the paper like it was trying on sincerity to see if it fit.

I RSVP’d yes. Not because I was eager to audition for a second act in the same play, but because boundaries work best when they are used more than once. Marcus put the event on my calendar. The Phantom would come again, not as a flex but as punctuation. If appearances were going to be a language, I would speak it fluently and truthfully. And if the room didn’t have a chair with my name, I had learned something useful: I could bring my own. “Cocktail attire,” it read. Under the printed lines, in Victoria’s looping hand: Looking forward to celebrating with the whole family.

I RSVP’d yes. Marcus confirmed the Phantom. Some lessons have to be taught more than once; some boundaries must be redrawn until the paper remembers their shape.

I think about that night at the Metropolitan Club more than is probably useful. Not because of the Rolls‑Royce, though it did the quiet work of a gavel. Not because of the Instagram post, though it held a mirror up to a kind of cruelty that prefers to be called taste. I think about the kitchen, and the sous-chef who asked a simple question, and the way the staff made a space for me without pretending it made sense. I think about how a life can be edited until it looks good in a certain frame, and what it costs to refuse the edit.

At Mom’s birthday party, they served me dinner in the kitchen… “with the help.” “You understand?” Victoria smiled. “It’s about appearances.” I ate quietly and said, “Of course.” When my Rolls‑Royce pulled up, the entire party went silent. That silence didn’t feel like triumph. It felt like clarity, like the room had finally been lit properly. The scene hadn’t changed. I had.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

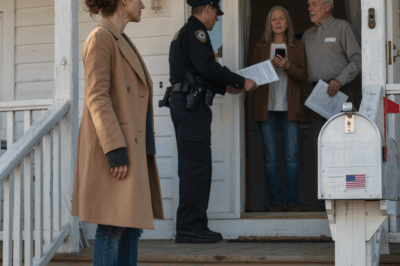

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load