The first time I met the judge who would decide whether my daughter slept under my roof or someone else’s, he pushed his glasses up the bridge of his nose and asked me a question that was more like a weather report. “Mr. Mercer, will you be making a statement today?”

I said, “No, Your Honor.”

Truth doesn’t shout. It waits. It waits the way a fisherman waits, the way dawn waits just below the horizon. I’d learned that lesson late, somewhere between the smell of a new perfume in our house and the soft click of a lock on an office door that never used to be locked. By then, words had been weaponized. Mine were never going to win a volume contest with Laura’s.

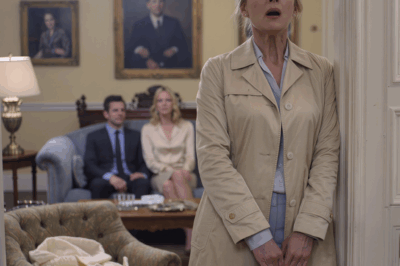

Laura sat across from me at counsel table, her posture carved in marble, chin slightly lifted, a navy sheath dress that made her look like the kind of woman who could command a boardroom and never lose a strand of hair in the wind. Her attorney, Gideon Strauss, had the practiced warmth of a pastor and the precision of a surgeon. He told a story about me: a man prone to anger, to control, to storm clouds that rolled in without warning. He told the judge I wasn’t safe for a six-year-old girl.

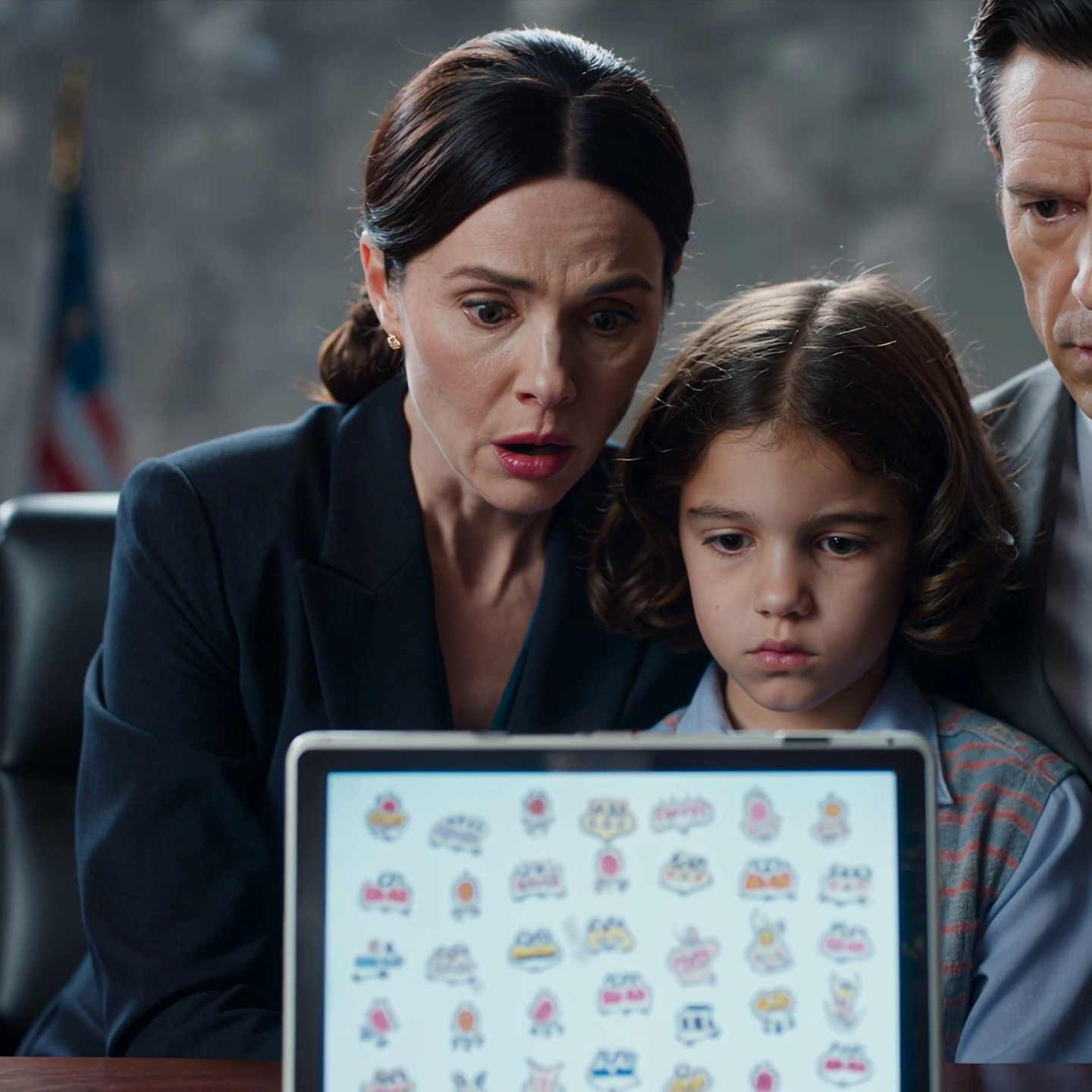

I didn’t interrupt him. I watched the hands of the courtroom clock trudge along, every second the sound of a nail being tapped into soft wood. My daughter, Grace, sat on a bench behind me, a small constellation of stickers spread across the back of her tablet: a rainbow, a ballerina, a yellow dog with floppy ears. She swung her legs, heels knocking softly against the bench in a rhythm only she knew.

“Call Grace Mercer,” Strauss said, and his voice wore politeness like cologne.

The judge adjusted his glasses again, an old habit that felt like punctuation. He looked at Grace and then at me. “Mr. Mercer, are you comfortable with your daughter…?”

I nodded because this had never been about comfort. It had been about accuracy. About what people say when they think the audience is asleep.

Grace came forward, both hands on the tablet the way you carry something that matters more than you do. She looked at me once, like the quick squeeze of a hand, and then at her mother. “Can I show you something Mommy doesn’t know?”

Laura’s smile had always been flawless—thin, symmetrical, a line you could draw with a ruler. It flickered. Just enough to reveal the bones underneath.

The judge hesitated. “Who recorded this?”

“I did,” Grace said. “By accident. I was under the blanket fort.” She blinked as if that explained everything, and somehow it did.

The judge gave a small nod. The clerk took the tablet. The screen glowed. And then the room filled with a sound that should never belong to bedtime: a voice made of ice and mockery. Grace’s camera wasn’t steady; the footage swam softly, the way a child’s world moves when they hide and listen. But sound never lies. My wife’s voice didn’t just arrive—it cut.

“He’ll never know,” Laura said to a man whose face, when it slid into frame, I recognized from office holiday parties and remembered with the sharpness that comes from understanding too late. “He’s too weak to fight me.”

Gideon Strauss stood so fast his chair skated backward. “Your Honor—”

The gavel dropped once. Then again. A second, slower beat. Silence took the room by the throat.

Laura’s smile broke in stages. Cheek first, then mouth, then eyes. The way a building doesn’t collapse all at once. She twisted toward me with a look I had trouble translating. Fear. Anger. The sudden math of losing. “You… you planned this?”

I didn’t answer. The judge didn’t let me. We watched. We listened. On the screen, a wineglass clinked, and Laura laughed like a stranger. My daughter had recorded the soundtrack to our undoing while hugging a stuffed dog under a blanket fort with the Christmas lights still plugged in.

When the tablet screen went dark, it left a rectangular afterimage in the air. The judge leaned back, folded his hands, and stared at my ex-wife as if she were a painting with a plaque that said: Untitled (Control).

We broke for lunch early. No one ate. Outside, on the courthouse steps, a wind came down Second Avenue that smelled faintly of rain and the river, and we all pretended to be people walking to cars.

Laura found me beside my truck in the parking lot. No cameras, no stenographers, just the white noise of tires and a faraway siren. “You think this makes you a good father?” she hissed. “Using her like that?”

“You used her first,” I said, and the calm in my voice didn’t feel like triumph. It felt like finally saying a true thing out loud in the right order. “She heard you, Laura. Children don’t forget what they hear at night.”

Her eyes filled, but not with remorse. Panic carries a different sheen. It’s the shine of someone counting exits. “I’ll fix this,” she whispered.

“No,” I said. “You’ll live with it.”

The wind shifted. Somewhere, a church bell tried to be brave in the middle of a weekday. She reached for me and I stepped back because her touch had become a stain I couldn’t scrub out.

I didn’t meet Laura at a gala or a conference or some glamorous New York thing. We met at a Fourth of July barbecue in East Nashville where paper plates buckled under the weight of ribs and potato salad and every beer can had a ring of water sweating into the heat. She laughed at a joke I made about fireworks being just the universe practicing handwriting. Her laugh didn’t just arrive; it wrapped itself around the porch.

She was a development director for a nonprofit that wanted to save the world one fundraiser at a time. I managed risk for a trucking company that got more patriotic around Labor Day than most people do on Veteran’s Day. We were both good at spreadsheets and solving problems with calendars. We were competent. Competent is underrated when you’re thirty.

Marriage with us was a clean kitchen and a shared grocery list app. It was knowing whose turn it was to take out the trash without speaking. Then Grace arrived, and the house learned a new language: the sigh of a baby monitor, the squeak of the rocking chair I never fixed because it was the soundtrack to three a.m., the small alien noises a newborn makes while sleeping on your chest. I learned how to braid hair by watching the same YouTube video twelve times. The first time I did it right, Laura took a picture of my clumsy pride.

I can tell you the exact Tuesday it began to rot. Rot isn’t loud; the wall looks fine from the living room until your finger goes through it. Laura started closing her office door for calls. She said donors expected professionalism. She started buying a perfume that smelled like new money and orchard air. She started saying I instead of we.

“If you need me, text,” she said one evening, and her phone sat face down like a sleeping animal that might bite if you touched it.

I didn’t go through her phone. I never broke into accounts. That’s not a declaration of virtue. It’s a practical statement. Rage is terrible at math. What rage doesn’t understand is that patience compounds. If truth waits long enough, it collects interest.

So I observed. Patterns, times, numbers. The rhythm of a lie looks a lot like the rhythm of a commute until you graph it. I kept a notebook in the bottom drawer of my nightstand and wrote things down like I was inventorying a warehouse: hotel receipts that didn’t match conference schedules, lunches that lasted four hours and cast shadows they shouldn’t have.

The assistant, when he came into focus, did so the way objects do when you stop squinting and admit what they are. Adam Cole. Fresh out of grad school. Relentlessly helpful. The kind of man who believed that falling for your boss was a noble accident. I’m not sure which of them first named the accident fate.

The night I found the hotel receipt, it had two glasses of wine printed on it like a confession wearing a bow tie. One bed. On the drive home, the radio played a love song so earnest I laughed alone in traffic. At our kitchen table, I laid the paper down the way you lay down a photo of a person you miss who isn’t dead yet.

“Client meeting,” she said without looking at the receipt, only at me. “You know how it is.”

“I do,” I said, and smiled as if we had just shared a private joke. Rage solves nothing. Information does. “We should check that the reimbursement policy covers this hotel,” I added, and her eyes stuttered over mine for a fraction of a second too long. People underestimate how much truth you can collect in half-seconds.

That night she kissed me like a rehearsal. Touch without confession. A choreography of apology that never learned the words. I watched the ceiling and memorized the pattern of the plaster because knowing your battleground helps you stop tripping over furniture in the dark.

When the divorce papers arrived in a large white envelope that wanted to look like snow, Laura was still the woman everyone liked at parties. She said I was controlling, distant, unsafe. She said I raised my voice. I do have a voice; it is not always soft. I also have a daughter who sleeps through storms because she knows which way the door opens.

I hired a lawyer named Alicia Monroe, who wore her hair in a simple bun and her contempt for nonsense like a second suit. “You don’t win these cases with speeches,” she told me. “You win them with receipts.”

“I have receipts,” I said, and handed her a manila folder that looked thin for what it contained.

“You also have a six-year-old,” she said. “Are you asking her to testify?”

“No,” I said quickly, because the word ask did violence to the situation. “I’m asking for the truth to be in the room.”

“Then we let it walk in the door by itself,” Alicia said. “If it wants to.”

The video walked in by itself.

Grace recorded it because children love forts and blankets that turn the world into a tunnel where everything sounds more secret, more important. Laura paced our bedroom and performed a version of herself so careless she forgot the old rule: microphones are everywhere now, especially when you think there aren’t any. Grace had climbed under the quilt with a flashlight to read a book about a yellow dog who solved mysteries. The irony has teeth I still taste. She pressed the camera by accident and left it running for thirteen minutes and twenty-two seconds.

When I found the clip weeks later, it was because she’d handed me the tablet to help her reset a game that wouldn’t load. The video thumbnail was my dresser at a strange angle with a sliver of Laura’s stockinged ankle and the hem of a pencil skirt like the last scenes in a movie you wish you’d left before the credits. I listened to Laura tell a man who was not me that I would never fight. That the court would believe her because she was better at light.

I watched it four times. Not to suffer. To measure. On the fifth, when my hands trembled, it wasn’t from shock; it was from recognition. I recognized the voice that had been speaking to me for months, the one that wore politeness like a mask you forget to remove before bed.

I didn’t confront her. You don’t interrupt a person with a shovel when they’re digging a hole you need. I transferred the file to a drive. I didn’t copy her phone. I didn’t even change my passcode. I took Grace to the park and pushed her on a swing while maple leaves learned how to let go around us.

“Daddy, how do you know when someone’s telling the truth?” she asked from the sky, and kids can do that—they can ask a question from a different altitude and make you answer from the soles of your feet.

“Most people aren’t good at pretending when no one’s clapping,” I said.

“What does clapping mean?” she asked.

“It means attention,” I said. “Some people live on it. Some people live without it.”

“I like peanut butter,” she said, which was the correct summary for the afternoon.

Alicia filed a motion to admit the video. Gideon blustered about authenticity and context and how a child’s accidental recording violated some invisible covenant of privacy that, I suspected, only applied to wives rehearsing their betrayals in bedrooms. The judge asked three questions about chain of custody and one about whether Grace understood the difference between truth and imagination. Grace said, “Truth is what stays the same even when people get mad at it.” The judge’s mouth twitched like a man who had not smiled on the clock in ten years and just remembered how.

The morning of the hearing, Nashville wore a gray sky that made the courthouse’s limestone look like a photograph from the 1950s. I ironed a blue shirt I would not remember by dinner and packed Grace’s lunch like it was any other day: turkey, apple slices, two pretzels she would trade for something more interesting. I tied her sneakers because she still didn’t like the last loop.

In the courtroom, Laura was flawless. Her hair, a neat knot. Her expression, composed. Her voice, rehearsed. Gideon carved me into a silhouette of a man who scared his family when he walked down the hall. I didn’t dignify the fiction with a counter-story. Fiction loves arguments; it feeds on them. Facts prefer quiet rooms.

Grace asked to show the judge something. And then the world changed by inches, on a six-year-old’s timeline.

The ruling came in the afternoon, in a voice that did not want to be dramatic but couldn’t help it. The judge spoke about credibility, about patterns, about damage done offstage that bleeds onto it whether the actors intend it or not. He said the words “full custody” to me while he looked at Laura as if she were a case study in how a story can turn on its author.

I didn’t celebrate. I took Grace to the library because that’s where quiet lives. She chose a book with a dog on the cover again, as if the universe were nostalgic. We sat at a round table that had been carved with a dozen initials by children who would someday vote and forget they had ever dented oak with keys.

“Is Mommy coming back?” she asked without looking up from a picture of a dog in a detective hat.

“Not for a while,” I said, because I would rather live in a world where my daughter trusts me than in one where I win rhetorical contests with my conscience. She nodded and turned the page.

At home, the evening learned our new shape. Dinner at six. Bath at seven. Bed at eight. I told stories that were not about courtrooms or recordings or women who choose smoke over mirrors. I told stories about boats and the names of constellations and a yellow dog that solved mysteries with a nose for lost mittens. Grace laughed at the same place every night for a week.

Laura’s world didn’t collapse so much as it deflated. Friends stepped back in that careful way people do when they’re afraid criticism is contagious. The man she’d bet on left town before the ink dried. The nonprofit gave her a leave of absence that sounded like a coat check ticket no one intended to redeem. I didn’t let myself be glad about any of it. Not because I’m saintly, but because gloating is a kind of theft. It steals from the future where you still have to look your kid in the eye.

We started therapy. Tuesday afternoons. An office with a blue rug and a small basket of fidget toys that looked like aliens. The therapist was a woman whose voice made even the word “schedule” sound like a lullaby. Grace drew pictures of houses with three windows and a door, the classic child architecture, but her doors always had a small heart on them. The therapist told me that was a good sign. “A heart means home,” she said. “It means there’s room.”

Sometimes at night, when the house is so quiet I can hear the refrigerator hum like a distant power line, I get up and look at the tablet on Grace’s desk. The screen is cracked now, a thin white lightning bolt across the top corner. I keep it charged. Not as evidence. As a reminder. The reminder isn’t of Laura. It’s of a six-year-old who thought to put truth in a place where adults would have to trip over it.

On Saturdays, we go to Shelby Park and watch the river pretend it’s going somewhere important. We throw sticks for other people’s dogs and drink hot chocolate too hot for tongues that small. Grace learned to ride a bike in a straight line, then a wobbly curve, then a circle so wide we both got dizzy laughing. There’s a kind of joy that arrives like a clean wind—you don’t hear it coming until it lifts the hair at the back of your neck.

Once, at the grocery store, we turned into an aisle and ran into Laura by accident. She wore sunglasses inside like a shield, a habit that says, Don’t look at me unless you are paparazzi. She reached up and touched Grace’s cheek with her fingertips as if the skin might argue with her. “Hi, bug,” she said, and I swallowed the grammar of an old life.

“Hi,” Grace said carefully, as if hello were now a fragile word on a high shelf. We stood there, three people between the cereal and the cookies, and learned that you can be a family and not be one at all.

“I’m getting help,” Laura told me without preface, her voice as level as a promise made to a mirror.

“I hope it helps,” I said, and meant it, and also understood that hope is a thing you give away without expecting change.

At night, after stories, I sit on the edge of Grace’s bed while she negotiates the politics of one more sip of water. “Daddy?” she asks when the room is almost dark.

“Yeah?”

“Were you scared?”

“Yes,” I say. “But do you know what scared and brave have in common?”

“What?”

“They both show up to the same place.”

She thinks about that until thinking turns into sleep.

People ask, in that clumsy way humans have when they want gossip disguised as concern, if I hate Laura now. Hate is simple and useful, like duct tape. It fixes nothing permanently. I don’t hate Laura. I don’t love her either. What I feel is a smaller thing with sharper edges: I will not be written by you. I will not be directed by someone else’s fear.

A year passes the way years do when measured by seasons and school concerts. Kindergarten becomes first grade. Grace loses her first tooth and puts it in a sandwich bag under her pillow because a bag feels official. She tells the tooth fairy she accepts both cash and coins. Her handwriting grows out of the wobbles the way a sapling learns not to lean.

On the anniversary of the court date, I take her to the courthouse steps in the late afternoon. The sun drops along the limestone and turns it the kind of gold that makes even bad memories look cinematic. We sit on the steps and share a pretzel that tastes like salt and a year we survived.

“Why are we here?” she asks, tugging at my sleeve.

“Because places are stories,” I say. “And some stories are worth rewriting.”

She leans against me and points at a pigeon with the solemnity of a queen. “That one’s mine.”

“Take good care of it,” I say.

I could tell you I’m healed and mean it. But healing is a road that keeps changing its mind. Some days the road is straight. Some days it’s gravel. On the worst days, it’s a loop that tries to convince you you’re back at the beginning. Those are the days I make pancakes. Consistency is a soft kind of victory.

The night sometimes brings a question I can’t answer with a bedtime story. “Will Mommy ever live with us again?” Grace asks, her voice soaked in the kind of hope that doesn’t know yet it’s heavy.

“I don’t know,” I say, because any other sentence would be a betrayal of the trust I’m trying to build like a house with the right number of windows. “But I know this: you live with me. Now. Tomorrow. And the day after that.”

She nods in the dark and lets go of the day.

On my dresser, there’s a photograph in a wooden frame. Not of a wedding or a baby or a beach. It’s a picture of a porch on the Fourth of July in East Nashville ten summers ago, paper plates buckling, beer cans sweating. Laura is in it, laughing at a joke about fireworks. I keep the photograph not as proof of a thing that failed, but as proof that we are constantly writing ourselves, and sometimes we change fonts. The porch is still there, I’m sure. Somebody else’s story is talking on it now. That’s fine. A life is not a courthouse. It does not need a gavel to be real.

Every so often, I find a sticker under the coffee table—a rainbow, a ballerina, a dog. They adhere to the places you don’t look often. I peel them up and smooth them onto Grace’s tablet, which charges on the desk like a small sun. The crack in the glass looks like a scar healed well enough that you forget why it’s there until you catch the light at the right angle.

We drive past the courthouse sometimes on the way to the park. Grace waves out the window like it’s a parade float. I nod at the building the way men nod at each other in gas stations at two in the morning. Respect. Recognition. Distance.

Laura texted once in the spring and asked if we could talk. I sent her Alicia’s number because there are conversations that belong to professionals the way certain surgeries do. She didn’t like that. I don’t like root canals either.

On the day Grace learned to whistle, she ran through the house like she’d invented steam. I laughed so hard I had to sit down on the kitchen floor, where the tile was cool and clean and looked like a chessboard that had finally run out of opponents. She stood over me, whistling a sound that was more air than note, and I realized I was not angry anymore. Tired. Wiser. But not angry.

Victory, it turns out, is not a banner you hang. It’s a bedtime you keep. It’s a lunch you pack with apple slices arranged into a smile you know your kid will notice and pretend not to. It’s the way the house settles after midnight, sounding like a heavy book being closed on a table.

I still believe truth doesn’t shout. It waits in the next room. Sometimes it waits under a blanket fort with Christmas lights glowing like tiny planets. Sometimes it waits on a hard bench in a courtroom while a six-year-old swings her legs and hums a song she can’t remember the words to. And sometimes, if you’re lucky, truth chooses you to carry it from one room to another without dropping it.

I am not a hero. I am a man who irons blue shirts and knows the schedule of bath time and can braid hair in the dark. I am a man who learned how to wait without rotting and how to stand in a parking lot while a person I once loved discovered that her hands didn’t work on the world the way she thought they did.

Grace will grow up and forget things I wish she’d remember and remember things I wish she’d forget. That’s the contract. She will make jokes about fireworks to someone on a porch someday and that person will laugh, and the sound will wrap around a summer night the way it always has. Maybe she’ll keep a notebook in the bottom drawer of a nightstand. Maybe she’ll journal. Maybe she’ll just live and never need to count.

When I turn off the light in her room, I glance at the tablet on the desk. The charging light is a tiny heartbeat. The screen sleeps, but the truth inside it does not. And I understand, with the kind of understanding that doesn’t require a gavel, that the stage was never Laura’s. It was never mine. It belonged to a six-year-old with a fort and a flashlight and the stubborn belief that if you press play at the right time, the world will have to listen.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

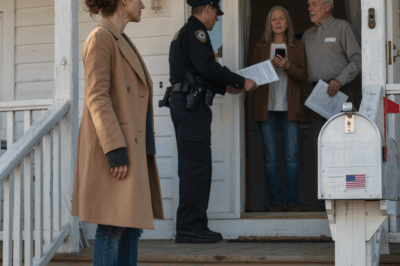

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load