The last thing I noticed before the room turned into a courtroom was the little American flag magnet on my mother’s stainless-steel fridge, holding a curling recipe card for pecan pie. Sinatra crooned from her Bluetooth speaker in the dining room—one of his smooth winter tracks my father swore by every Christmas—and the smell of honey-baked ham threaded through the house like a sales pitch for belonging. I’d set my contribution, a store‑bought pumpkin cheesecake, on the marble island and watched the magnet tremble when the fridge door closed. In the next room, crystal chimed and chairs scraped. My mother lifted her glass, the good cabernet she saved for speeches, and—without even looking at me—said, clear enough to cut a bow string, “We’re ashamed of you.” She laughed. People who wanted to stay on her good side laughed with her. I didn’t. I didn’t move at all. That was the first time I realized not moving can move everything else.

She had always preferred applause to affection. When I was eight, I drew her in red crayon at the kitchen table while she set out gingerbread cookie cutters: a neat oval face, careful swoop of hair, pearl earrings the size of marbles. I wrote “My hero” at the top and taped it crooked to the same refrigerator, the little flag magnet holding one corner like it was standing guard. My brother’s soccer medals were already lined up like a parade, my sister’s ballet program angled toward the room. By morning my drawing was gone. “It was crooked,” she said, dropping the crayon picture in the trash with the coffee grounds. That was the day love turned into inventory for me, an item you could lose if it wasn’t displayed straight.

When I got a full scholarship to a state university, she called it luck, not work. When I closed on a small one‑bedroom on the south side of town after years of freelance gigs and ramen, she said, “Don’t get ahead of yourself, sweetheart,” like ambition was a bright rug she was about to yank from under me. When my first startup failed spectacularly—server bills like albatrosses, the wrong investor at the worst moment—she didn’t hug me or ask me what I’d learned. She said, “I told you this would happen,” and set a casserole on my counter like a deed of ownership. Months later, at a cousin’s barbecue, I heard her whisper to my aunt behind the hydrangeas, “She embarrasses us. She thinks she’s better than everyone, but look at her. Alone, bitter, a failure.” They laughed. I stood by the condiments pretending to care about relish ratios and promised myself something that felt like a contract. Next time she tried to humiliate me, that would be the last time. I wasn’t going to explode. I was going to be precise. I was done auditioning for a part I already played.

If my mother—Evelyn—had a religion, it was control dressed as hospitality. The centerpiece was always perfect, the rules were always hers, and every holiday worked like a pageant where she wore the crown and we clapped on cue. She liked stories about herself: the tire she changed on I‑75 in heels, the church bake sale she turned into a fundraiser that paid for a new roof, the time she convinced a neighbor to donate a baby grand to the high school choir. She believed love should be grateful. She believed gratitude should be visible. Every December she polished her image like silver and sized everyone else accordingly. Control was her language; compliance was the translation she demanded.

So that year, I decided to speak another dialect. I arrived late on purpose—fifteen minutes past the time she texted, coat dusted with snow, hair back, black dress, low boots, the kind you can stand your ground in without wobbling. The house was staged for the catalogue version of us: evergreen swag on the banister, white lights on the porch columns, holiday cards fanned out on the entry table with names like Grant and Lily—my brother and sister—front and center. The tree wore decades of ornaments, including the lopsided felt angel I made in first grade that somehow survived the purge my drawing hadn’t. My father adjusted the TV over the fireplace to loop a Yule log; someone had dimmed the recessed lighting to let the candles “do their job.”

She gave me the once‑over that pretended to be concern. “You look tired,” she said, lips drawn into that polite smile that means you look awful. “It’s been a productive year,” I said, and hung my coat. “Oh?” She tilted her head. “So you finally got a real job?” She didn’t need a microphone. Everyone in a ten‑foot radius heard the line and the gentle chorus of chuckles it solicited. I smiled, because the one thing more alarming to a person like her than anger is a calm she doesn’t own. I followed the smell of cloves and cinnamon to the dining room and took my seat at the far end, the place where children graduate once there are grandchildren to fill their spots. Sinatra hummed from a speaker disguised as a candle. The crystal gleamed. The knives waited at attention.

Dinner is choreography at Evelyn’s table. You don’t interrupt. You don’t put elbows on the linen. You swallow your opinions with your sweet potatoes. She walked her routine: bragged about Grant’s promotion to VP at his firm, displayed Lily’s new engagement ring like a trophy she’d personally hunted, thanked the pastor’s wife for the cranberry compote recipe, and then—right when dessert plates were stacked like poker chips—she rotated the spotlight. “And you,” she said, as if the word itself were unpleasant to touch. “Still chasing those little projects?” She lifted her glass before the verdict, not after. “We’re ashamed of you.” She let the laughter breathe. The room obeyed. Power always sounds like laughter until it doesn’t.

I folded my napkin and stood. Not fast, not dramatic. Just enough to change the air pressure. Forks paused. Someone’s bracelet clicked against the underside of the table. My mother’s smile held, but I saw her eyes search the room for backup. “You know,” I said, and my voice didn’t need to be loud; it needed to be shaped, “I used to think the worst thing you could do to a child was ignore them. Turns out it’s pretending to love them while breaking them down for sport.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said, smile whitening. The trick of hers—deny the premise, keep the crown.

“You’ve spent your whole life making sure everyone knows how perfect you are,” I said, “but perfection doesn’t cry itself to sleep because its children stop calling. Perfection doesn’t numb itself with another glass to make the applause sound fuller. Perfection doesn’t need an audience to feel real.”

Grant looked at his plate like there was a message in the gravy. Lily shifted and set her hand over her fiancé’s wrist as if to hold him in place. My father cleared his throat and found the water pitcher fascinating. “You said you were ashamed of me,” I went on, steady as a metronome. “But the truth is, I stopped being ashamed of you a long time ago.” I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t need to. “You raised us to fear you. Fear fades. Once it’s gone, all that’s left is pity.”

I could see the tremor move through her face, the way you can watch wind cross a field of wheat. The room shrank to the size of the truth.

“You wanted an audience,” I said softly, almost kindly. “Now you have one.”

Tears gathered at the lower lash line, brief and brave, then her face surrendered. The first tear cut through her foundation like a rivulet through fresh paint. She opened her mouth and sound came out but nothing that arranged itself into words. There was a small gasp from someone down the table, a polite wobble of a candle flame as if even the wax had opinions. Sinatra kept crooning, obscenely cheerful.

I set my napkin on the table, the way a guest leaves a tip, and I walked out. No slam, no scene, no door. Just the cool of the foyer tile and the sharper cool of December on my cheeks. The porch lights shone their perfect, catalog glow. I stepped into it and felt none of it stick. Sometimes leaving is the loudest sentence you can write.

She called that night. I didn’t answer. She texted, “You humiliated me.” I didn’t reply. Over the next forty‑eight hours, the phone insisted on being hers: buzzing on the kitchen counter, blinking on my nightstand. On the third morning I woke to a notification screen that stacked the same name over and over until it became a design element. 29 missed calls. My brother finally texted, “She won’t stop crying.” I stared at the numbers, set the phone down face‑down like a dealt card, and let it ring itself out. My phone lit up; I let it burn out.

I didn’t do it to make her cry. That wasn’t the point and never had been. The point was the line I drew when I was eight and didn’t have the language for it yet: the difference between image and love. I had paid for the difference my whole life—in compliance, in apologies shaped like thank‑you notes, in showing up with casseroles and silence. If she’d fainted, I would have called 911. If she’d been in danger, I would have driven across town in the snow. But tears aren’t emergencies when they’re the price of hearing yourself at last.

In the days that followed, I cleaned my apartment the way you clean a thought: pulled everything from the fridge and wiped the shelves, threw out condiments that had been pretending to be food for months, donated the clothes I kept “in case,” sorted the junk drawer that could have won a contest for chaos. On a whim at the thrift store, I bought a small magnet—a flag, like the one on my mother’s fridge, only this one had a tiny nick in the blue field where a white star was missing. I stuck it to the corner of my own stainless steel, then took a sheet of printer paper and wrote “My hero” in red marker in my worst handwriting and smiled at how it looked crooked on purpose. The magnet didn’t straighten it. That was the point. The flag had always been there; I just needed to claim my fridge.

Grant texted again a week later. “She’s not sleeping. She says you hate her.” I typed and erased three replies before leaving the cursor blinking. When he finally sent, “Can you at least talk to Dad? He’s worried,” I called my father. He kept the conversation on safe terrain—weather, the car, how the pastor’s Christmas Eve service ran a little long this year—and then landed, clumsily and honestly, on, “You could’ve said it nicer.”

“I said it true,” I told him. “Sometimes nice is just a way to keep the lie dressed.”

He sighed, a sound like a screen door in wind. “Your mother’s… she cares about what people think. Always has.”

“I know,” I said. “I finally care more about what I think.”

Lily sent a single message the day after New Year’s: a photo of the table set for brunch, a place card with my name in my mother’s hand at the far end, holly‑wreath napkin ring standing guard. “In case,” the caption read. I didn’t answer. If there was going to be a seat for me, it would not be at a table where you have to earn your chair each course.

The beautiful thing about a line is that once you draw it, it helps you live. I started saying no—not dramatically, not with press releases, just no. No to fixing my mother’s printer at ten p.m. because the church newsletter had to go out by morning; no to being the third parent on family group texts that treated me like the free therapist; no to the tidy legacy of being the “difficult one” who existed to make everyone else look cooperative by comparison. Work grew quieter and then richer. I picked up a contract that led to another contract, made rent without counting backwards, bought fresh flowers because this month didn’t have to survive last month’s panic. I joined a Thursday night trivia team at the bar down the block and met Mel and Patrice and an electrician named James who explained why my living room breaker kept tripping. On Saturdays I brought coffee to the elderly neighbor across the hall and let her talk about her years as a nurse—ER shifts that ran on adrenaline and miracles. She pressed a folded child’s drawing into my hand one morning—her granddaughter’s self‑portrait in red crayon. “She made two,” Mrs. Keating said. “I thought you’d like one on your fridge.” I put it up under the nicked flag magnet and didn’t mind that it leaned.

I didn’t go to Easter. I didn’t go to Mother’s Day brunch. In July, when the neighborhood hung flags on their porches, I noticed mine in miniature on the stainless steel, steady as any tradition that gets chosen instead of assigned. In August, a distant cousin got married and I sent a gift card because the registry made assumptions about a closeness we didn’t have. In September, Evelyn sent a long email shaped like an apology but padded with disclaimers, the kind that uses the word “if” a lot. If you felt judged, if you misunderstood my humor, if I have ever made you feel small. I typed back exactly one sentence: “I heard you.” She called twice. I let both go to voicemail and then deleted them without listening. Sometimes the most generous thing you can offer a pattern is indifference.

By the time the next Christmas rolled toward town and parked itself on the calendar, my apartment felt like it belonged to a person I recognized. I bought a small Norfolk pine and strung it with cinnamon sticks and white lights, tossed a plaid blanket over the sofa arm because it looked like a magazine told me to, and queued up a playlist that included Sinatra because traditions don’t have to be loyal to pain. A friend from trivia, recently divorced and one renter’s deposit lighter, came over with a lasagna that would have made my mother put her hand over her heart. We ate off plates that had hairline cracks and drank cheap Chianti and put our feet on the coffee table because it’s my coffee table. Mrs. Keating’s granddaughter rang the bell with a Tupperware of sugar cookies and shy eyes. We sent her home with chocolate and a puzzle we’d finished twice and a promise to come by for carols. The night folded itself into something you can call joy when you don’t need permission.

At ten o’clock my phone lit with a family group text I still hadn’t left, more out of anthropological curiosity than duty. The picture came first: the long dining table, the evergreen runner, the crystal glasses catching light, the place card with my name at the end like a raffle ticket laid facedown. My mother’s caption said, “All set.” A minute later, another photo, my father in his Christmas sweater, Grant in his new watch, Lily with a baby bump I hadn’t known to expect. Then the video: my mother lifting her glass and saying something I couldn’t hear over the room’s murmur. She smiled when she hit Send. Control hates daylight.

I closed my phone and stared at the little tree, at the crooked red crayon drawing on my fridge under the marred flag magnet. I thought about how many hours I had spent at that long table managing everyone else’s weather. I thought about how management isn’t love. I thought about how leaving last year had felt like stepping off a stage and onto a street where nobody knew your lines and that, for once, was the gift. The quiet in my apartment wasn’t empty. It was available.

Some stories end in grand reconciliations, the kind where people learn lines you wrote for them in secret and recite them back to you with perfect timing. Mine didn’t. Mine ended with a different kind of generosity: I left them to their stage and built my own room. There were consequences—it would be dishonest to say otherwise. An aunt stopped calling. A cousin posted a passive‑aggressive meme about “honoring your parents” that got just enough likes to do its job. My father learned the art of double life, carrying news between our houses like a man shuttling fragile glass. My mother started sending postcards from places she would have insisted we call “vacations” when we were kids and call “trips” in adulthood: “Thinking of you,” the first one read, as if thought could do the job of listening. I put them in a drawer with expired coupons. I wasn’t collecting proof anymore.

Grant called me in March to say they’d had to bring my mother to the doctor because she wasn’t eating well. “She says she has no appetite,” he said, annoyed at the inconvenience of it all and protective at once. “The doctor says it’s just… stress.” He waited, and I found myself waiting with him for what he wanted me to promise. “I’m here,” I told him, and I meant on the planet, not at the house. He exhaled like he’d been holding his breath for months. “Okay,” he said. “Okay.” We talked about the baby—Lily’s—and how much the stroller cost and how money can be a language you don’t realize you’re speaking until you’re translating for yourself.

If you’re waiting for the big scene where we sit down and say everything perfectly, you’re waiting for my mother’s version of a finale. The truth is simpler and more ordinary. She will always be good at arranging chairs. I will always be good at refusing the ones that require a costume. We may find each other in the middle someday, on a porch where a flag moves in the kind of wind that doesn’t ask for applause. Or we may not. Both are peace I can live with.

What remains are the parts I can touch. The magnet on my fridge is chipped and a little tacky and it keeps holding on. The drawing under it tilts, stubborn and cheerful. The lasagna pan is clean, back in my friend’s hands for the next party. The trivia team is terrible at geography and brilliant at ‘80s lyrics and for once my skill set fits a conversation without being cross‑examined. Mrs. Keating tells me ER stories about Christmas Eve births and the one time a choir came through the halls singing “Silent Night” off‑key and how the off‑key made it better. She calls me kiddo and I don’t correct her.

Sometimes when I wash dishes at night, the window over my sink reflects my apartment back to me like a picture in a frame store. If I squint, I can imagine the long table at my parents’ house, candles guttering toward their stubs, the last slice of pie nobody wants but someone will eat so it doesn’t look like waste. I can see the place card with my name, the napkin ring, the glass tilted and waiting for a toast that will not come. I wish them health and an honest appetite. I put my plate in the rack and leave it to dry.

A week after this year’s Christmas, my mother left a voicemail that was just breathing. I played it twice to be sure. Then I deleted it. Not because I didn’t care, but because I did, and caring doesn’t mean surrender. I am allowed to love the part of her that sang harmony to Sinatra while she basted a turkey and to say no to the part that needed me to be a mirror. Both can be true. Both are true. The life I’m building doesn’t require an audience.

On New Year’s morning I made tea and wrote three lines on a sticky note, stuck it under the flag magnet beside the crooked drawing, and read it out loud to an empty room that did not feel empty at all. “Tell the truth. Keep your seat. Let the laughter belong to those who need it.” I straightened the sticky note and let it slip crooked again. The magnet held. For the first time, I wasn’t the one ashamed.

Truth doesn’t always end a story; most days it just changes the genre. The week after New Year’s, after I’d taped my three lines under the chipped little flag and felt my apartment exhale, my father called mid‑afternoon and asked, not ordered, if I would meet him for coffee. He said it like someone who had practiced the sentence in the bathroom mirror: one small ask, no stage directions. I said yes with three conditions. No audience. No speeches. No rewriting history while I was sitting there to hear it.

We picked a diner halfway between my place and theirs, the kind that smells like buttered toast and has pies under plastic domes next to the register. The TVs were playing a college bowl game on mute with subtitles marching like ants. A waitress with a Christmas‑tree pin on her apron left over from last week asked if I wanted the coffee hot or “hot hot.” “Hot hot, please,” I said, and wrapped my hands around the thick white mug like it could hold the whole plan.

My father arrived first in his navy windbreaker, hair flattened by a knit cap. He didn’t hug me; we have never been a hugging family unless a camera is pointed at us. He said, “You look good,” and for once it sounded like observation, not evaluation. We sat. We ordered eggs we didn’t need. He cleared his throat and started with football and weather—safe nouns. When he ran out, he placed both palms on the Formica like he was steadying a boat. “Your mother would like to come.” He looked at me when he said it. I looked back and didn’t blink. “Okay,” I said, “but remember my three conditions.”

Evelyn walked in ten minutes later, wearing the camel coat everyone in her church admires, scarf tied the way she saw on a morning show. She scanned the room by reflex, found our booth, and stopped on the threshold of the aisle like a person approaching a pool and considering the temperature. When she slid into the seat across from me, the smell of her perfume carried Christmas Eve services and lemon cleaner with it. She set her purse down, then moved it, then folded her hands. For a long beat, the only sound was the kitchen bell and Sinatra—of course Sinatra—leaking softly from the ceiling speakers. The world likes a motif.

“I don’t want a scene,” I said quietly.

“I didn’t come for one,” she answered, and for a surprise, it sounded true.

We ordered her tea because coffee “isn’t ladylike after lunch,” one of her rules no one asked for. The waitress brought everything and called me honey and my mother ma’am and that tiny equalization took the static out of the room by one degree. Evelyn kept her eyes on the clock above the pie case and then on me, as if she had to re‑choose where to look.

“You made me cry in front of everyone,” she said, a fact laid on the table like a check.

“I told the truth in front of everyone,” I said. “Those are cousins. Not jurors. I decided to stop being one of your props.”

She flinched. “I’m not perfect.”

“I never asked you to be perfect,” I said. “I asked you to be kind.”

She looked down at her napkin, then up at me. “I thought I was… keeping standards. The family’s reputation.”

“Reputation is other people’s mirror,” I said. “Love is the hand on a shoulder when the mirror cracks.”

She swallowed, the tiny muscles in her throat working the way truth makes them work. My father traced a finger along a coffee ring on the table. Sinatra hit a note he’s hit for seventy winters. The kitchen bell chimed. Somewhere in the diner a child laughed at a straw wrapper like it was a magic trick.

“I can’t undo years,” she said finally, small and almost to herself.

“I’m not here for undoing,” I said. “I’m here for the next chapter. If there is one.”

“What does that look like?” She asked it like there might be a diagram I could hand her.

“Three things,” I said, holding up three fingers like I was teaching a class and not renegotiating a lifetime. “No more public shaming or jokes at my expense. No more triangulating—if you have something to say to me, you say it to me. And if we’re going to try, we start with twelve sessions. Family counseling. Tuesdays at two. I already called a place. I’ll send the info.”

She blinked, as if I’d handed her a schedule instead of a sword. “Counseling,” she repeated, tasting the word like a foreign candy. “Twelve?”

“Twelve,” I said. “Because ten sounds tidy and we have never been tidy.”

My father exhaled; he had been waiting. Evelyn nodded once, sharp. “If I do this, you’ll come back? To Christmas?”

“I’ll come to counseling,” I said. “And we’ll see.”

The waitress slid our bill into a vinyl sleeve and tucked it by the ketchup. My mother reached for her purse. “Let me,” she said, which in her vocabulary used to mean leverage. “No,” I said gently, and put my card down. “This one’s mine.” It wasn’t about money. It was about authorship. Câu bản lề: An apology without change is just a new coat of paint.

We did the twelve. Tuesdays at two, a room with earnest chairs and a box of tissues staged like a centerpiece. The counselor had the kind of calm voice I might have mocked at twenty and am grateful for at thirty‑three. We talked about rules nobody agreed to out loud but broke as if we’d signed them in ink. Evelyn tried to narrate. I interrupted and explained the difference between narrating and owning. She tried to reach for old lines. I handed her new ones and waited while she tried them on for fit. My father surprised me by telling a story about the night before their wedding, about how she ironed his shirt and set his alarm and taped a list to the door and how he mistook that for devotion when it was, in fact, forewarning.

At the fourth session, Evelyn brought a photo of me at eight with bangs too short and pride too big, clutching a participation ribbon at a school art fair. “This isn’t the drawing,” she said, holding the photo like an apology, “but it’s the same day.” Her voice bumped on the word same. “I don’t know why I took the picture and not the picture you made.”

“Because the photo was straight,” I said before I could stop myself. She smiled, pained and honest. “Because the photo was straight,” she agreed.

The counselor wrote two words on her pad, then turned it so we could see: seeing vs. being seen. She circled them both and then the space between. We looked at the circle like people stare at a map, hoping the right highway will light up.

At the sixth session, Evelyn cried the kind of tears that don’t chase attention. The counselor didn’t reach for the tissues; she let them sit. My mother told a story about her own mother, a woman who used compliments like coupons—good for one use only, expires soon. She said, “I thought if I kept everything perfect, I could hold onto people.” I said, “You can’t hold people that way without squeezing.” She nodded. She said it back to me so she would hear herself say it. We let the room be quiet for a minute. Quiet didn’t feel like punishment anymore. It felt like a porch light left on.

At the ninth session, Evelyn tried to make a grand gesture and pulled out her checkbook like a magician producing a dove. “Let me help,” she said. “Tell me what you need.” She wrote 7,000 in the amount line before I could stop her, zeros round as pearls. I put my hand over the check. “What I need isn’t on paper,” I said. “But if you want to put money somewhere, donate to the elementary school’s art program. Buy a thousand red crayons for girls who tape crooked pictures to refrigerators and need them to stay.”

She stared at me. Then she tore the check from the book and, very carefully, ripped it in half, then in half again. Two days later, I got a confirmation email from the district foundation with a receipt for 19,500 USD. The memo line said: In honor of crooked drawings. I printed it and stuck it under my magnet, nick in the blue field and all. Câu bản lề: A boundary isn’t a wall; it’s a door with my hand on the knob.

By the twelfth Tuesday, we were not a new family; we were a family with new terms. The counselor said we could space the meetings out and call if the ground started to tilt. On the way out, in the parking lot, my mother touched my sleeve, not to stop me, just to prove to herself the world was still physical. “What now?” she asked.

“Now we practice,” I said. “People don’t get fluent in a language because they bought the dictionary.”

September brought baby clothes to Lily’s spare room and the smell of new paint. Grant texted me pictures of a lopsided crib he swore would hold a rhinoceros. I sent a laughing emoji and a link to a better screwdriver set. My father started sending me photos, too—mundane little dispatches that felt like trust: the neighbor’s dog asleep on their porch, the new mailbox flag he installed, the first red leaf on the maple out front. My mother didn’t text pictures. She sent four words once: “I’m trying, sincerely, Evelyn.” She signed her own name like she wasn’t hiding behind a title.

In October, the ladies at church asked Evelyn to coordinate the harvest dinner, the one she could command in her sleep. She said yes and then called me and did something unheard of: she asked what I thought. “If you’re asking me, keep it simple,” I said. “Less performance, more chairs.” She laughed, a real sound, brief and human, the kind nobody accompanies. She said, “Less performance, more chairs,” like she was writing a recipe. Câu bản lề: Forgiveness isn’t a seating chart; it’s a verb you do privately.

And then December came, as it always does, with Sinatra and lists and the sharpness of air that makes you tilt your face to breathe. My mother mailed an invitation to a Christmas brunch at their house—nothing embossed, just a card with holly from the drugstore and her handwriting in blue pen. No group text photo of a table set like a stage. No place card with my name in advance. Inside the card, one sentence: “If you come, I promise no toasts.” I held the card a long time, like it might warm if I didn’t rush it.

I decided on a middle that wasn’t our old end. I invited them to my place first.

“Brunch at my apartment,” I texted the family thread. “Casual. 11 a.m. Bring nothing but yourselves. Rules posted by the door.” Grant replied immediately with a thumbs‑up. Lily sent three hearts and a “Do I get to bring cinnamon rolls or are rules rules?” My father wrote, “We’ll be there at 10:58 because your mother doesn’t know how to be late.” My mother waited three minutes and typed, “We’ll be honored.”

The morning of, I taped a sheet of paper to my door under the small flag magnet I’d moved there for the occasion. It said:

-

No toasts.

No rankings.

If you break a rule, you clear a dish and try again.

I put Sinatra on low because he belongs to me, too, brewed coffee strong and “hot hot,” set out plates with hairline cracks I’d grown fond of, and slid a store‑bought pecan pie next to a pan of eggs baked with peppers and cheese. Mrs. Keating left a note on my doormat that said, “I’ll sing you something through the wall.” It looked like a lyric.

They came on time like a carefully trained habit. My father kissed my cheek and brought a poinsettia he admitted he’d bought at the gas station. Grant held a bag of oranges we didn’t need. Lily moved slowly, hand on the small of her back. Evelyn stepped over the threshold like entering a different decade and stopped at the rules taped to my door. She nodded at each one. “I can do this,” she said aloud, to herself more than to me.

She stood in my kitchen and found the magnet with the nicked star on my fridge and the crayon drawing under it—a new one from Mrs. Keating’s granddaughter that said MY HERO in jagged red letters over a stick figure with crooked hair. My mother touched the edge of the paper like checking if it might hold. “It’s crooked,” she said, voice unsteady. I waited. “And it’s perfect,” she finished.

We ate. We didn’t toast. When my father started to announce something about Grant’s promotion by reflex, he saw the rules and pivoted into a question about the coffee that made us laugh for the right reason. Grant told a story about dropping a socket wrench into the crib and inventing three new words his child shouldn’t learn yet. Lily asked me about my Thursday trivia and said if I needed a ringer for ‘90s pop, she was my girl. My mother told a quiet story about a woman from church who never learned how to say sorry and had to write it on a cake—and how the bakery still wrote it wrong. We let the story be itself. We cleared our own plates.

At the sink, Evelyn stood shoulder‑to‑shoulder with me, drying. “I don’t know how to do this,” she said. “Not the way you do.”

“You do it like this,” I said. “You show up. You read the rules. You ask before you assume.”

She nodded. “I can read.”

“I know,” I said. “You taught me.”

After they left, the apartment felt big in a good way. My phone buzzed. A text from my mother: “Thank you for not making me an audience.” Under it, a photo of her fridge at home: the tiny flag magnet straightened, the crooked felt angel from first grade holding a recipe card. No place card with my name. No stage.

Two days later, an official letter arrived from the school foundation on paper with a watermark that made me absurdly happy. They’d used my mother’s donation to stock art carts across five elementary schools—crayons, paper, scissors with blunt tips, glue sticks that wouldn’t dry out by lunchtime. Enclosed was a list of the first‑grade teachers’ notes: “We made winter trees with crooked trunks!” “Javier drew his mom as a superhero!” “Sasha says her crayon stayed red even when she pressed hard.” I read the notes and thought of how many refrigerators were going to have uneven magnets working double duty.

On Christmas Eve, I walked to the little park at the end of my block. Houses wore their lights like good intentions. Somewhere a neighbor sang a carol off‑key and a dog joined on a harmony only he understood. I sat on a bench and thought about doors. My phone buzzed again; a voicemail. I listened this time. My mother’s voice, careful: “I’m making your grandmother’s sweet potatoes and they are stubborn today. I thought about calling you to ask what I’m doing wrong and then remembered you never liked them. We’re trying the recipe without the marshmallows. That feels brave. I’m… proud of you. No toast. Just me. Goodnight.”

I didn’t call back. I didn’t need to. There are conversations you can only have by living.

That night, before I went to bed, I took the sticky note from New Year’s last year and wrote one more line beneath the three I’d already taped under the chipped flag: “Make room for the crooked.” I read all four lines out loud to a room that has learned how to hold them. Câu bản lề: I didn’t need her to be different to be whole; I needed me to be consistent.

The next morning, while coffee made the apartment smell like effort, I opened the drawer where I’d kept the postcards my mother sent during the quiet months. I didn’t throw them away. I didn’t display them either. I tied them with kitchen twine and set them on a shelf labeled Miscellaneous, because not everything has to be a thesis. On my fridge, the flag magnet held steady, star nick and all, giving gravity to a crayon drawing that didn’t mind its angles.

People like to ask for endings, as if life were a novel and not a neighborhood. This is mine: I go to trivia on Thursdays and come home with bad prizes and good laughter. I take Mrs. Keating to the grocery store because winter is slippery and pride is brittle. My father sends me pictures of the maple, which is brave enough to lose everything every year and still trust itself to leaf again. Grant brings his baby over and naps on my couch after two minutes of pretending he won’t. Lily sings the wrong verse to the right lullaby and nobody corrects her. My mother comes to counseling when she needs it and stays home when she doesn’t, and sometimes she texts a photo of a crooked card on her fridge with no caption. I keep my three rules by the door and add a fourth when I need it. The laughter in my life belongs to people, not to power.

One last thing, because it matters: when I visit their house now—sometimes, not always—there is a small American flag magnet on the fridge holding a list that simply says: Milk. Eggs. Listen. I run my finger over the magnet’s edge and feel where the paint chips and the metal starts. It’s a reminder I can tuck in a pocket without taking anything from the house. Love is not a performance on holidays; it’s the mundane in between, how you speak when no one’s clapping.

And if next Christmas someone lifts a glass and looks my way, I’ll point to the rules by the door and we’ll eat our pie, Sinatra humming, plates with their hairline cracks holding like champions. The story isn’t neat, but it’s honest. The magnet holds. The drawing leans. The door is mine to open and close. For the first time, and for the last time that needs saying, I’m not the one ashamed.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

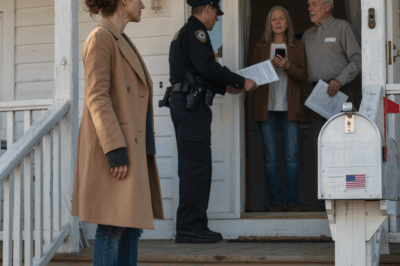

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load