My name is Amelia Hart, and the moment my life split in two, the conference room still smelled like dry-erase marker and burned coffee. The projector hummed, the skyline of Chicago flattened into a grayscale blur on the glass behind a ring of colleagues checking their phones. Mine lit up with TYLER across the screen. I stepped into the hallway, into the hush between the elevator chime and the distant rattle of the L, expecting the usual. How’s the trip? When do you land?

“I’m divorcing you,” he said. No hello. No warm-up. Just the blade.

The carpet under my heels might as well have dropped away. “Excuse me?”

“I’ve already sold the apartment,” he added, tone almost triumphant, like he’d finally found the lever to pry me out of my own life. “So you’ll need to figure out where you’re going to live. Enjoy that.”

For one long, suspended heartbeat, I forgot to breathe. And then, against all reason, I laughed—quiet and incredulous. The audacity. The casual cruelty. A part of me cataloged the details the way I always do: the cold air conditioning on the back of my neck, the glint of a safety exit sign, the way his voice curled around the word sold, as if what we built could be converted to cash without passing through me at all.

“You sold the apartment?” I asked, voice steady.

“Yeah,” he said, dry laugh. “Nicole and I need the money to set up our life together. She deserves better than a tiny place like that anyway.”

The name hit with the dull sting of confirmation. I had suspected another orbit for months—late nights, last-minute trips, the gradual erosion of eye contact—but to hear him say it like I was the intruder in their future lit a fire in my chest.

“Sounds good,” I replied evenly, and I ended the call with my thumb as if I were turning off a lamp.

Back in the room, someone was explaining third-quarter projections. My face arranged itself the way women’s faces learn to: attentive, pleasant, unremarkable. My notes were suddenly immaculate. I nodded at all the right moments while a different part of my brain unpacked the truth: Tyler thought he’d won. He thought he could pull the rug out from under me, sell the home I’d chosen, dismantle the life I’d stitched together stitch by meticulous stitch—and walk away clean.

One thing Tyler did not know: the deed to that apartment had been in my name alone for months.

We had refinanced in March to lock a lower rate; he signed a quitclaim at Lakefront Title with barely a glance, more interested in the latte art than the paragraphs. The Cook County Recorder’s stamp had dried before the ink on his signature. He liked to say he trusted me with details, which in Tyler’s vocabulary meant he didn’t read. Carelessness had always trailed him like cologne.

By the time I returned to my desk, shock had burned off into a clear, calm heat. I rescheduled my afternoon meetings with the soft authority of a woman whose priorities just rearranged. I booked an earlier flight. And then I called Chloe Garner.

Chloe and I met ten years ago at a charity 5K on the Lakefront Trail where she blew past me and then doubled back to drag me across the finish line. Now she was a real estate attorney with a voice like a gavel and a heart like a lighthouse.

“Tell me everything,” she said, no preamble.

I did. I told her about the phone call, the laugh, the way he said Nicole as if unspooling a lifeline.

“He sold the apartment,” she repeated, incredulous. “Does he even realize he can’t do that?”

“Apparently not.” I let a hint of amusement into my tone. “He thinks he’s already spent the money.”

Chloe’s chuckle was a blade exfoliating paint. “He’s in for a very rude awakening. We’ll notify the buyer and the title company immediately. The sale is invalid, Amelia. You have sole ownership. If he took any money, he’s flirting with fraud. I’ll draft a letter tonight. We’ll also record a lis pendens if needed to cloud title on any attempt to resell—belt and suspenders.”

The word fraud landed like the click of a newly installed deadbolt. “What do you need from me?”

“Deed copy, refinance packet, any emails related to the refinance or Tyler’s communications about listing or sale. If you have the recorder instrument number, even better.”

“I do.” Of course I did. I keep a life in little labeled folders. I opened my documents app and texted her everything.

“Got it,” she said a minute later. “Sit tight—no, scratch that. Go do something normal. I’ll call you when the buyer’s counsel calls me back.”

“Thanks, Chlo.”

“Amelia?”

“Yeah?”

“I’m proud of you for making that refinance move. You were protecting yourself even before you knew you needed to.”

On the flight home, I watched Chicago assemble itself from the air like a circuit board threaded with light. I used to think marriage was a promise of two people holding the same map. What I had was a man who barely looked at the directions and got mad when I took the wheel.

O’Hare at night is its own city. The taxi line breathed and shuffled. A skycap whistled something that reminded me of late-October high school games. I pulled my suitcase through the glass doors of our building on Washington, nodded to Luis at the desk, and rode the elevator up with a woman in scrubs who smelled like hand soap and fatigue.

Inside, the apartment was familiar and foreign at once—the lofted ceilings, the exposed brick, the antique map of the Great Lakes Tyler insisted on keeping even though he’s from nowhere near them. His jackets were slung over the same dining chair as always; his shoes were a hazard by the door; a mug with a dehydrated galaxy of coffee sat in the sink. I set my suitcase down and exhaled.

I pulled the fireproof folder from the bedroom shelf like a magician’s reveal and slid out the deed—my name alone, recorder’s stamp crisp, instrument number circled in blue from the day I double-checked it. Then I sat at the dining table that we argued over at Restoration Hardware and waited.

Tyler came in like a storm that had mistaken our doorway for a shoreline. Phone in fist, face flushed. “What the hell is this?” he demanded, waving at the email on his screen. “Some letter from Chloe saying the sale’s void? You’re telling me I can’t sell the apartment? It’s half mine.”

“It isn’t,” I said, standing. “The deed’s been in my name since March.”

His mouth opened and closed like he’d turned to the wrong page of a script. “What are you talking about?”

I held up the deed. “You signed a quitclaim at refinance, Tyler. You signed off on transferring your interest to me. You didn’t read it because you never read things you’re supposed to. You just assume everything bends around you.”

For a second, calculation flickered across his face, then the sneer returned like a reflex. “You think you’re so smart. This doesn’t change anything. I already made a deal. You’ll look like a fool when it all goes through.”

“The buyer knows,” I said, steady. “Chloe’s already spoken with their counsel. If you took any deposit, you’ll need to return it. If you spent any of it, you have larger problems than me.”

Color drained from his cheeks a shade. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Oh, I know exactly what I’m talking about.” I stepped closer. “You’ve spent years treating me like I was too naive to notice what you were doing. Guess what, Tyler. I’ve been paying attention.”

He started pacing, anger’s engine revving in place. “This is ridiculous. You’re blowing it out of proportion. You can’t kick me out.”

“Legally?” I raised an eyebrow. “I could. I’m not doing that tonight. I’m giving you the courtesy of time to figure out your next move. But let me be clear: I’m not leaving my home.”

Nicole showed up two nights later like a plot twist that had been foreshadowed in neon. She walked in on Tyler’s arm with a proprietary sweep of her gaze that made heat rise in my throat. She was pretty in that polished Midwest way—fresh blowout, pale pink nails, a perfume that smelled like a department store’s promise.

“So this is where we’re staying,” she said, hand tightening around her tote strap as if testing ownership by touch.

“This is where Tyler was staying,” I corrected. “You won’t be staying here at all.”

Her smile slipped, and she looked at him. “Tyler?”

“She’s being unreasonable,” he said, voice pitched to perform concern. “We’ll be gone soon. I already sold—”

“You didn’t.” I felt something inside me go cool, clean. “You tried to sell something you don’t own. That sale is void. And if the buyer wanted to make your life hell, they could.”

Nicole blinked. “What is she talking about?” She turned to him, the angle of her jaw hardening. “You told me the apartment was yours. That you sold it.”

“It’s complicated,” he said, palms up, the universal gesture of a man trying to hold water in his hands. “I’ll handle it.”

“It’s not complicated,” I said. “Tyler doesn’t read paperwork. He signed away his interest months ago. He tried to sell my home anyway. The buyer has counsel. So do I.”

The room hushed in that odd way rooms do when truth pulls the plug on noise. Nicole’s mouth opened, then closed. “Fraud?” she whispered, the word like it had teeth.

“If he took money under false pretenses,” I said. “I haven’t checked the title company’s disbursements because I don’t care to, but others will.”

She took a step back, as if something in the air had shifted density. “You didn’t tell me any of this,” she said to Tyler, voice rising. “You said you had everything handled.”

“I can fix it,” he said, desperation thin as tissue. “Nicole, I just need—”

“Don’t,” she said, cutting him off with a small, sharp hand. Her eyes slid to me. “I didn’t sign up for this.” She pivoted, heels clicking, and left without looking back.

Tyler sagged onto the sofa, the fight leaking out like air from a punctured tire. “Amelia, please.” He rubbed his face. “We’ve been together six years. You can’t just—”

“You did that when you called me at work to announce a divorce and the sale of my home,” I said. “You didn’t just betray me, Tyler. You tried to erase me. I’m done being erased.”

I set a folder on the coffee table and slid it toward him. “That’s the divorce paperwork. Chloe drafted it. You’ll want to sign quickly.”

He stared like it might explode. “You really hate me that much?”

“I don’t hate you,” I said, surprised to find it true. “I feel sorry for you. You had someone who loved you and a home we built, and you traded it for your own reflection.”

He left before midnight with two suitcases and the gaming chair I’d wanted gone for years, an obscene relic wheeled down the hall like an apology for taste. I changed the locks in the morning—new deadbolt, new keypad code, the soft click of the bolt like a benediction.

Recovery looks deceptively like ordinary life. I still woke to my alarm at 6:30, still laced my running shoes, still jogged past the river to watch the light climb the silver ribs of the Merchandise Mart. The city kept being itself—CTA trains screamed and sighed, a florist on Lake Street hosed down his sidewalk, a man in a Bears cap argued lovingly with a barista about espresso.

Lauren came by that night with Thai takeout and a bottle of wine. Lauren is the friend who shows up with tape and labels and mercy.

“Is he gone?” she asked, dropping onto my sofa with the grateful noise only women who kick off heels truly understand.

“Gone,” I said, and the word tasted like clean water.

“To fresh starts,” she said, raising her glass. “And to the day you stop underestimating yourself.”

We boxed what had been his—ties rolled into neat spirals, socks balled and tossed, framed jerseys I let him have because I no longer needed to prove I could accommodate someone else’s shrine. I labeled each box in my careful handwriting. It felt like curating a museum exhibit for a man who never learned the difference between possession and love.

Chloe called the next day with updates. “Buyer’s counsel is cooperative and furious,” she said, not bothering to hide her satisfaction. “Lakefront Title confirms no funds were disbursed beyond an earnest money deposit that’s being returned. I sent Tyler a formal demand and a sternly written primer on ‘reading.’ Also, I filed a notice with the Recorder just to be annoyingly thorough.”

“You’re a marvel,” I said.

“I know,” she replied dryly. “How are you?”

“I’m okay.” I glanced around the sunlit living room, at the empty space where a gaudy coffee table had squatted. “Better than okay.”

“Good. By the way, a therapist I trust is taking new patients. Dr. Mira Singh. No pressure. I only mention because major life events scramble our wiring and then we wonder why we smell smoke.”

I wrote down the name. Help, I’ve learned, is a form of intelligence.

At work, I remembered who I am when my energy isn’t spent repackaging someone else’s behavior. I led a pitch and didn’t apologize for sounding sure. I said “I disagree” in a room where I used to soften impact with ten qualifiers. Our team won Kore & Co., a beauty brand that hired us precisely because we sounded like we knew our own mind.

The apartment softened around the edges of all this. I moved my grandmother’s cedar chest to the foot of my bed, hung the black-and-white photo of my parents laughing at a county fair, replaced the too-bright overhead with a pendant that turned evening into a warm hush. I took the map of the Great Lakes down and leaned it against the wall of the hall closet where inconvenient things go to nap.

A week after he left, Tyler texted for the first time. The messages stacked—apologies diluted with excuses, half-formed attempts at guilt. I made a mistake. Can we talk? You’re going to ruin me. Do you want that? I didn’t respond. Not because I was angry—though I was—but because the quiet felt like a muscle I’d finally discovered and did not want to fatigue.

Dr. Singh’s office had a blue rug that looked like the lake in February and a ficus that had outlived a thousand confessions. She asked gentle, disarming questions that made honesty feel like luck.

“Why do you think you refinanced the way you did?” she asked at our second session.

“I like order,” I said. “I also like sleeping at night.”

“Both can be true,” she said. “It also sounds like your intuition whispered and you listened before your reasoning could file an appeal.”

“My intuition’s voice was hoarse,” I admitted. “I kept telling it to be nicer.”

We laughed, and the laugh landed in my chest where previously there’d been a draft.

Once, exiting my building with a trash bag in one hand and my phone in the other, I nearly tripped over a golden retriever sprawled across the lobby like a throw rug with a heartbeat. “I’m so sorry,” said the man at the other end of the leash, standing too quickly and knocking his shoulder into a column. He wore a navy ball cap and the kind of grin that makes people forgive things.

“It’s fine,” I said, smiling despite myself. “He’s perfect.”

“Objectively,” the man agreed, scratching the dog’s head. “I’m Evan. We’re new to the building. This is Moose. We’re learning to be civilized.”

“Amelia,” I said. “I’m learning that too.”

We rode the elevator together with Moose’s head pressed against my knee. I thought about the weird optimism of animals—how they approach every new person like a door that might open to a room full of bacon and applause.

Two Saturdays later, on a bright morning rinsed clean by overnight rain, I took a bag of books to Open Books on Hubbard. Bookstores smell like permission. I traded the thrillers Tyler loved for a stack of women who told the truth about themselves and then survived it. On my way back, I ran into Evan and Moose on the sidewalk where small, ordinary life happens. We walked to the farmer’s market and argued pleasantly about peaches versus nectarines. He never once asked me a question that contained the answer he wanted to hear.

“Do you want to get coffee?” he asked at the end, like it was a question and not a test.

“Not today,” I said, honesty easy. “But I’d like to, another time.”

“Great,” he said, not flinching. “We live in the same building. Time is weirdly generous.”

It is, when you stop throwing it into a pit.

The divorce moved the way paperwork moves—slowly at first, then all at once. Chloe shepherded it through with surgical precision. Tyler signed without fanfare. Nicole, I heard from a mutual acquaintance, declined a starring role in his aftermath. I wished her luck, in that way you wish well to someone you hope never to see again.

One afternoon in late November, the light thin and exquisite, Chloe and I sat at a small table at Beatrix in River North, her laptop open between us like a tiny theater.

“You’re officially free,” she said, tapping a key for punctuation. “Dissolution entered. Property acknowledged. No maintenance. Clean break.”

“Thank you,” I said, meaning for more than the document. “For everything.”

She waved it away and then didn’t. “I do this for a living,” she said, “but it never stops being satisfying when a woman gets her house back and her voice with it.”

On the walk home, I paused on a bridge to watch the river seam the city in two. Tourists took pictures of themselves against a backdrop that will be posted with captions about pizza and wind, and a man in a suit held a paper cup of coffee like it was the only warm thing he owned. I thought about the apartment in terms of hours—how many hours I’d spent there being smaller so that someone else could feel larger, and how many hours now opened like windows.

I didn’t sell. Not right away. I painted the second bedroom a deep, decisive blue and turned it into a study with a door that closed. I invited my parents to visit and let my mother fuss over my spice drawer and pronounce the cumin situation dire. I hosted Lauren’s birthday and cried laughing when she made a speech about friendship that veered into an improvised rap and then refused to be ashamed.

December arrived with the kind of cold that gives Chicago her reputation. I bought a ridiculous parka that made me look like a competent marshmallow and wore it with pride. Evan and I traded elevator small talk for lobby conversations for, finally, a coffee at Intelligentsia where Moose rested his head on my boot and Evan admitted he’d once gone to law school for a year and realized he liked people too much to be good at it.

“Some people are extraordinary at the law because they love it,” he said. “I loved the people it hurt. That seemed like a problem.”

“What do you do now?” I asked.

“Carpenter,” he said, and then, because men who are settled in themselves don’t need to be impressive, he added, “I make shelves. Also tables. Occasionally regret.”

New Year’s Eve, Lauren and I split a bottle of sparkling wine in my kitchen while the city prepared to invent itself again for a day.

“Do you ever think about what you put up with?” she asked softly when the silly gave way to the real.

“All the time.”

“And do you forgive yourself?”

I leaned against the counter and watched our reflections in the dark window. “I’m trying,” I said. “I think forgiveness tastes like letting yourself have the good without checking over your shoulder for the audit.”

We toasted to that, to us, to Chloe, to Moose, to the woman I was before I forgot and the woman I am now that I remember.

Spring made a surprise entrance in March. Snow turned to lace at the edges of sidewalks. I woke one morning to the sound of a street-sweeper and knew the city had decided to be kind for a weekend. I opened my windows and the apartment inhaled.

On a Sunday, I stumbled across a folder I hadn’t noticed in the back of a kitchen cabinet—a Tyler folder, because they all are, until they aren’t. Receipts, a credit card statement I didn’t recognize, a printout of an email thread with a lender whose name made my scalp prickle. Tyler had applied for a personal loan using an inflated version of our household income and a fabricated side business under my name.

The old panic rose, a phantom limb. I sat down. I breathed. Then I texted Chloe a photo of the paperwork with a single line: Do I need to set something on fire?

She called. “No arson today. Send me everything. We’ll place fraud alerts with the bureaus, pull your credit, and file police reports if necessary. You did nothing wrong. We will make that the official story.”

It turned out the lender had declined the application, a small mercy delivered by an underwriting algorithm that finally did me a favor. We still placed the alerts, still documented the attempt, still built a paper fence. The difference this time was not the outcome but the way my body held itself through the process—upright, grounded, unflinching.

In April, Kore & Co. invited our team to Los Angeles to present the brand refresh we’d been building for months. I stood in a room ringed with palms in gold pots and talked about an American woman we had dreamed on paper: intelligent, unbothered, complicated, not apologizing for any of it. I realized mid-sentence that I was describing the woman I’d been busy becoming while I wasn’t looking.

After the presentation, I took a late flight back and returned to the apartment just before midnight. The city hummed like a hive. I set my suitcase down and walked out onto the small balcony to watch the river lights. Behind me, my home waited—warm lamp glow, stack of books, a vase of tulips Lauren had left, a small brass key dish by the door that held only my keys.

I did not need a grand ending to write meaning on what had happened. Sometimes a quiet life is the fiercest rebellion.

In May, on a day when the sun understood its assignment, I finally made a decision I’d been circling. I listed the apartment. Not because I needed to run from it but because staying had done its work. I hired Evan—yes, my neighbor, the carpenter—to build a walnut dining table as a going-away gift to myself, a piece of beauty that would outlast the walls around it. He measured and sketched in the afternoon light while Moose attempted to eat a measuring tape.

“Where are you going?” he asked, pencil tucked behind his ear.

“Logan Square,” I said. “A little coach house with a yard where I can fail at tomatoes.”

“That sounds perfect,” he said, and meant it.

The apartment sold for over asking in a week to a couple who stood in my kitchen and looked at each other like people who cannot believe they get to build a life. I left them a note with my favorite coffee shops, the trick for opening the stubborn balcony door, and a recipe for my grandmother’s lemon bars. I thanked the rooms. I touched the brick. I locked the door and slid my keys across the counter for the last time.

I moved into my coach house in early June. Lauren came over with a potted herb I can never keep alive and a determination that this time I will. Chloe sent a bottle of champagne with a card that said: To the woman who reads everything and chooses herself. Evan installed the table and said it looked like it had always belonged—then stayed for pasta and told me a story about the first shelf he ever built, which collapsed dramatically and taught him more about humility than any class.

If you’re waiting for Tyler to reappear, to bang on the door and ask for absolution, know this: sometimes the past has the decency to stay in the past. He texted once in July. I did not respond. I was busy learning the names of my neighbors’ dogs and the sound of summer rain on a different roof.

On my thirty-fourth birthday, Lauren, Chloe, and Evan gathered around the walnut table, and we played a game where you say one true thing you’ve learned this year. When it was my turn, I said: “I am allowed to be safe in my own life.”

No one clapped. They didn’t need to. We sat there, sunlight folding itself across the wood, the city bending itself around our little square of peace. Somewhere up the block, a child screamed with joy. Somewhere downtown, someone signed something they didn’t read. Trains carved the air. The American flag on my neighbor’s porch lifted and fell. Ordinary rapture.

Later that night, alone with the kitchen light off and the living room lamp turning the room to honey, I thought about that first phone call in the hallway months ago—the smug certainty in Tyler’s voice, the way the word sold had sounded like a gavel. I thought about the deed tucked away, my name on it like a promise I’d made to myself. I thought about all the small, boring, exquisite ways a woman chooses her own life and how those choices add up to a house you can live in.

This wasn’t just the end of a marriage. It was the start of something I hadn’t known I was allowed to want: a life where my voice fits in my mouth and my name fits on my deed and my days fit inside my skin. I washed the wineglasses, set them upside down on a linen towel, and turned out the light. The table sat there in the dark, solid and gleaming and mine.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

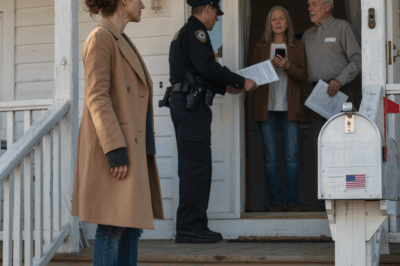

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load