I believed my mother’s text the way I had believed a thousand small mercies before it. “Everyone’s staying home due to the ice storm. Christmas dinner is canceled. Stay safe.” I looked out my Nashville window anyway, as if the sky could be wrong about itself. The light lay clear over the neighborhood, the air cold but bright, the kind of December day that leaned toward blue instead of gray. I made hot chocolate, turned on an old movie, and told myself that staying in could be peaceful, that quiet could be a gift. It was the kind of lie I’d gotten good at telling myself—clean, small, easy to swallow.

I was thirty‑two and good at other kinds of tidy, too: spreadsheets, reconciliations, ledgers that clicked closed like a puzzle solved. I was an accountant at a mid‑size firm off West End, the dependable one who stayed late and kept promises. In my family, I was the quiet sister, the one who ironed the rough edges out of other people’s mistakes. Anna, two years younger, was the sparkle—the child my parents swore had sunlight in her bones. Any room she entered adjusted its furniture to make more space. I learned early how to fold myself smaller, how to hold a tray, how to applaud.

The house smelled like cinnamon and cocoa. The Christmas playlist shuffled to Elvis and then to Ella. Around three, with the movie murmuring in the background, I picked up my phone to scroll. I don’t know why I tapped on Instagram. Habit, I guess. Hunger, maybe. The first image filled the screen before I could brace for it: my cousin Nia had posted a carousel of photos—“Perfect family Christmas at Anna’s. So blessed.”

I didn’t breathe for a few seconds. I touched the glass like I could smudge the image away. There was my mother, the red cardigan she wore when she wanted pictures to pop. My father stood beside the turkey, carving knife lifted like a conductor’s baton. Aunts, uncles, cousins, my grandmother with her pearls, even the neighbor from two doors down who always brought ambrosia salad. They were arranged around Anna’s reclaimed‑wood table, lit by a golden chandelier she’d found at a market in Franklin. The windows behind them were a mirror of the day outside my own: clear and sun‑washed. No ice. No storm.

In the second photo, my mother placed her signature snowflake cookies in a perfect ring on a cake stand. In the third, my nieces and nephews tore at wrapping paper, their faces bright with the high sugar of joy. In the fourth, Anna, hair in a glossy knot, blew out the candles on a chocolate torte while everyone leaned in to be part of her air. There were strings of white lights looped around the banister and a sprig of mistletoe hung with a shiny red bow. In none of the photos was there an empty chair where I was supposed to be. The caption said “family traditions.” I stared and tried to locate myself anywhere in the frame: a plate set for me, a napkin with my initial, a glass that waited. There was nothing.

My hot chocolate went a skin on top. That wordless minute, before the meaning lands with both feet, can feel like standing on a porch and realizing the step is one lower than you expect. My stomach lurched. I scrolled again, and again, because we negotiate with truth the way we negotiate with weather—maybe it will change by the next hour. It didn’t. The ice storm had never existed. The cancellation was not mercy; it was choreography.

When my mother called the next morning, she made her voice soft, the “we tried” voice she wore to bridge over other people’s feelings. “Honey,” she said, “I hope you had a nice quiet Christmas. We missed you.”

I set the phone on speaker and looked at the laptop where Nia’s post still glowed like a bruise. “Did you,” I said, and was proud my voice didn’t shake, “miss me at Anna’s?”

Silence is a shape. On the other end, I could hear my mother rearranging the furniture of her story. “Well,” she said lightly, “Anna pulled it together last minute. And you know how you are at gatherings—so quiet. We thought it might be… less awkward this way.”

“Away from me,” I said. “Less awkward away from me.”

“Don’t be dramatic,” she sighed, and the mask slipped just enough to show the bone underneath. “Anna wanted everything perfect.”

All the little unremarkable unkindnesses—every “canceled” brunch that wasn’t, every game night I learned about from photos posted later, every shift of plans that left me pretending I preferred the silence—arranged themselves into a pattern so obvious I almost laughed. It was like the moment a Magic Eye poster resolves into a dolphin: once you see it, you can’t unsee. “How many,” I asked softly. “How many other times have you lied to me?”

“You’re being oversensitive,” she said, quick as an old reflex. “This is exactly why—”

“Why what?” I asked. “Why you cut me out unless you need me? Why Anna is the hero of every story and I’m the problem to fix?”

“That’s not fair,” my mother said, and her voice went stern, maternal, like I was twelve again and had risked the good dishes. “We love you both. But Anna makes the effort to be part of the family. You’re always so busy with work.”

“Busy paying your mortgage when Dad’s consulting dried up,” I said, and kept my voice even. “Busy taking three weeks off to drive Dad to appointments when he had his surgery while Anna took selfies and left for a yoga retreat. That busy?”

“If you’re going to be like this,” she said, brittle as icicles, “maybe it’s better if we give each other some space. Call me when you’re ready to be reasonable.”

The line clicked. The apartment felt suddenly like it belonged to me. Thirty‑two years re‑sorted themselves in the quiet—the honor‑roll certificates I’d stuck with magnets on the side of the garage fridge because the front was full of Anna’s ballet photos; the day we toured art schools and my father frowned ceiling‑ward and said, “Accountants don’t starve,” and I believed him enough to reroute my whole life; the Thanksgiving last month when I brined the turkey and chopped onions until my eyes stung and watched my mother praise Anna, who had sprinkled parsley over the potatoes like confetti. It was all there, a map I’d refused to read.

When I typed the email to my entire family, my fingers didn’t hesitate. I am an accountant. I am good with receipts.

I attached screenshots: my mother’s “stay safe” text and Nia’s bright carousel. I wrote plainly, the way a ledger lists what is and is not: You did not forget. You invented a storm. You did not spare my feelings. You arranged them. You did not cancel Christmas. You canceled me. I hit send.

The replies came fast. My aunt Marie said I misread the situation and should let the Lord work on my heart. Uncle Robert suggested I was overreacting, a word families use like a rag to blot out any stain that threatens the sofa. Nia deleted her post, then messaged me to say I was “causing unnecessary drama.” Anna wrote three paragraphs about energy and harmony and how she wanted one perfect evening for once, which she claimed I do not understand how to give. My father did not email; he texted a single sentence that smelled like the boardroom: “Family matters are not for public display.” My mother called mutual friends to suggest I was fragile. By sunset, I was the villain of a play I had not auditioned for.

I put my phone face down and made tea. The kettle sang. The city moved beyond my window, clean and ordinary. Somewhere in me a rope snapped free of a mooring and coiled home. I wasn’t angry in the way that sets fires. I was done in the way that builds new houses.

Rachel Parker messaged me a week later. She had been my parents’ financial advisor for years before she retired; I remembered her voice from my childhood as the calm one in rooms where men competed to be loudest. “Catherine,” her text read. “I’ve seen the posts. There is something you don’t know. Can we meet?”

We chose a quiet coffee shop off 12th Avenue South, the kind with a chalkboard menu and succulents in mismatched pots. Rachel wore a navy sweater and the kind of expression people wear when they are about to do the right thing late. She slid a manila envelope across the table and kept her fingers on it for a second before letting go. “Your father swore me to keep this confidential,” she said. “But I’ve carried the weight of it long enough.”

Inside the envelope were bank statements, trust documents, tax returns, and a copy of a power of attorney I recognized by my own quick teenaged signature at the bottom. I remembered the day I signed it: at eighteen, at the kitchen table, my mother setting a glass of orange juice beside the paper and telling me it was for emergencies, a routine thing families did to be prepared. We were leaving for my freshman year move‑in the next morning; my father had hugged me so hard my collarbone hurt. The signature was neat, the way I wrote when I wanted to be seen as good.

Rachel’s voice threaded through the thrum of the café. “Your grandfather, William Blake, set aside funds for your education and for your start in life. Three hundred thousand dollars, placed in a trust with your father as trustee. He intended for you to have access at twenty‑five. These statements show that shortly after your twenty‑third birthday, your father began moving those funds—first into an account in his name, then into your sister’s accounts, labeled as ‘investments.’ He also sold two small properties your grandfather left to be split between you and Anna, signing for you under the power of attorney.”

I traced the dates. The first transfer happened the same spring I took a second job at a bookstore to cover rising tuition. The second aligned with the summer I moved back home to save money and paid my parents rent I couldn’t afford because “we’re all tightening belts.” I remembered my mother’s hand on my shoulder as she told me I was sensible. I felt the earth tilt a fraction.

“I didn’t want to believe it,” Rachel said softly. “But every audit trail ends in the same place: Anna’s lifestyle—the studio leases, the retreats, the flights to Bali, the marketing packages—was funded by your inheritance. I have emails from your father pressuring me to make the transfers. I told him it wasn’t what the trust specified. He told me I didn’t understand family.”

I turned the pages. The numbers stacked like a translation of a language I didn’t know I was speaking. I hadn’t imagined it: the thinness I had been asked to live inside so someone else could wear the world like a robe.

“Why now?” I asked.

Rachel met my eyes. “Because the posts about you being unstable made me ill. Because he made me complicit. Because if your grandfather were alive, he would be standing next to you in court.” She folded her hands. “What they did isn’t just ugly; it’s unlawful.”

I walked home with the envelope inside my coat. The sky had that pale winter look like it was saving its strength for evening. I put the papers on my dining table and did what I do when chaos knocks—I built a file. I labeled tabs: TRUST. TRANSFERS. PROPERTIES. POA. CORRESPONDENCE. Then I opened my laptop and built a timeline. Each entry was a date laid on a blade. The work steadied me. I enlarged numbers until they filled the screen and sat with them until they stopped being snakes and became rope I could pull. When I reached a place I couldn’t pull alone, I called a lawyer.

Sarah Chen’s office overlooked the Cumberland, glass that caught light all afternoon. She wore her hair in a sleek bob and spoke in the clean sentences of someone who preferred facts to theater. She paged slowly through my binder, asked precise questions, and ran a finger along the margin of the POA. “This is overly broad for an eighteen‑year‑old,” she said. “And unconscionable when used to transfer assets you didn’t consent to.” She closed the binder. “We have a strong claim for civil recovery and, if you choose, grounds to refer for criminal charges—fiduciary abuse, conversion, fraud.”

I thought of my grandmother’s pearls shining in Anna’s dining room. I thought of my father’s text about privacy. I thought of the moment Anna placed her palm on my shoulder at Thanksgiving and whispered, “Relax your energy, Cat,” like my usefulness was to absorb the heat so she wouldn’t sweat. I didn’t crave spectacle. I craved the feeling of a door clicking shut on a room where I had never been welcome. “We’ll do this by the book,” I said. “We’ll give them a chance to make it right. And then we’ll do it by the law.”

On a Saturday morning that smelled like coffee and floor cleaner, I arranged three folders on my dining table. Each one contained copies: the trust statements, the transfer records, the emails Rachel had printed, the property deeds filed without my knowledge, and a letter on Sarah’s letterhead that explained their options with the unheated tone paperwork uses—return the remaining funds with interest, sign a confession, or face civil and criminal proceedings.

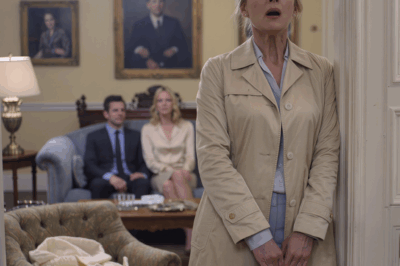

My parents arrived together, my mother in a coat the color of holly berries, my father in the navy blazer he wore like a uniform. Anna trailed them, wrapped in a cream sweater, the same glossy knot against the curve of her head. My mother opened her mouth to begin a speech about healing. I slid the folders across the table.

“Before you say a word,” I said, “please read.”

The silence then was different from the silence after my mother’s phone call; this one had weight, like snow coming down heavy. My father’s eyes moved across lines. The color drained from his face in stages—sternness, surprise, calculation, fatigue. My mother’s fingers fluttered at her pearls. Anna’s mouth pressed into a thin line, the expression she wore when the mirror showed her something she couldn’t rearrange into beauty.

“This is ridiculous,” my mother said finally, brittle. “You’re blackmailing your own family.”

“I’m offering a choice,” I said quietly. “Return what’s left with interest. Sign the confession. Or the police will explain the rest.”

“Rachel should be ashamed,” my father said, edges of fury sharpening his words. “What we do with our money—”

“It was my money,” I said. The rage in me was not hot. It was precise, a scalpel instead of a torch. “Grandfather left it for me. You were the trustee. You used a power of attorney you told me was for emergencies to sell property I didn’t consent to sell. You routed funds through your accounts to Anna’s. You lied, and you watched me work extra shifts and take on loans and help you pay bills I wouldn’t have needed to pay if you’d honored the trust.”

Anna’s eyes filled. “I didn’t know,” she whispered. “They said it was from their savings.”

“The transfers are labeled,” I said, and I placed a page in front of her where her name sat beside numbers that looked obscene under fluorescent kitchen light. “You knew when you signed the lease for the second studio. You knew when you booked Bali that spring I moved home. You knew when you posted ‘self‑made’ under a photo of your hands in prayer at sunrise.”

My mother switched tactics. “Sweetheart,” she said, voice syruping, “think about what this will do to the family. To your father’s reputation. To your sister’s business. To the church.”

“I did,” I said. “For a very long time. For your entire convenience. You have forty‑eight hours.”

They left in a disordered hush. My father took his coat from the chair back with a little jerk, as if the fabric had wronged him. Anna walked down the hall like the floor might dissolve. My mother looked back at me at the door, as if she could retrieve the old version of me with a look. I returned her gaze and did not move.

By evening, the family group thread throbbed. Aunts declared me ungrateful. Cousins used the word toxic the way you use a spray bottle on a stain. My grandmother did not text; she never learned how. I turned my phone off and cooked myself an omelet with chives and ate it slowly, as if food could teach memory a new lesson.

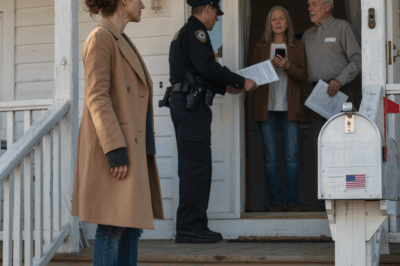

At hour forty‑nine, Sarah filed the civil action and sent the criminal referral. By afternoon, a detective called to say the warrants were approved. I went to work because that’s what I do. I put my hair up, wore my navy blazer, and reconciled a set of accounts for a client who needed his cash flow to look like a river instead of a clogged pipe. At three, I stepped into the break room for water and saw the local news flicker on the wall‑mounted television. I did not recognize my father at first. He looked smaller being led across a parking lot by two officers, his blazer bunched at the shoulder. My mother stood near the open door of the house, her hands pressed together, the neighbor’s ambrosia salad maker watching from her front yard as if the sidewalk had finally grown interesting. A camera panned to the yoga studio as a woman taped a notice to the glass.

I did not feel vindicated. I felt something ease in my ribs, like the space grief had been renting out was suddenly vacated. When my phone buzzed with the news alerts, I turned it face down again. In the stairwell, where no one at the office could see me, I cried once, quickly. Then I washed my face and went back to my desk.

The fallout unfolded in the predictable choreography of public shame: headlines, speculation, the temporary fame of outrage. People whose censure had once controlled me scurried to safer positions. My father’s colleagues who shook his hand at church looked down at their bulletin programs. Anna posted a blank square about “taking time to heal” and then disappeared from the apps. The ones who had called me dramatic fell briefly silent before rehearsing a new script in which they had always had concerns.

Rachel texted: You did the right thing. Your grandfather would be proud. I believed her. Pride wasn’t the sensation, exactly. It was a clean floor under bare feet, cool and solid.

The legal process ate months the way a machine eats paper—no flourish, just steady intake. My parents accepted plea deals. Restitution was ordered. The yoga studios closed. The houses sold. The family photo wall in Anna’s entryway came down in a hush. My grandmother, who had put her pearls back in their velvet box, called me on a landline that still clicked when picked up. “Are you eating enough?” she asked. “Do you have a warm coat?” She did not apologize for the others; she never had that power. She only loved me in a way I could feel, a bowl of soup set down in front of my hurt.

I didn’t stay in Nashville. I tried. I walked the dog‑friendly streets and learned which coffee shop made a latte that didn’t taste burned and which bakery overcooked its scones. But every lane had a memory at the end of it. In August, when the heat rose off the asphalt like an argument, I packed my car and drove west, then north, landing in Denver with the certainty I wanted—clean edges of mountains, air that asked lungs to be brave, light that made windows honest.

I found an apartment in a neighborhood that put children’s chalk drawings on the sidewalks and flags on porches on the Fourth of July. At work, I moved into a senior role and cleared a backlog that had made smart people panic. I bought a coat that made me look like someone who knew where she was going. On Sundays, I walked where the city ends and the foothills consider their options, and I learned the names of clouds.

One afternoon, almost a year to the day after the Christmas that stood me up, Rachel flew out to visit. She wore hiking shoes that made her laugh at herself and claimed the altitude made the coffee taste better. We sat at my small table by the window while flakes of the first snow turned the world outside into careful lace. She set an old photo album down, the kind with black corners holding images like promises. “I found this when I closed out a storage unit,” she said. “Your grandfather would want you to have it.”

I turned the pages slowly. There we were at the lake—the tiny version of me with a gap‑toothed smile that had not learned yet how to close; my grandfather in a flannel shirt, his hat brim shading a face lined from outside work and soft at the eyes. In one picture, he was teaching me to cast a line, his hands cupped over mine on the rod. I remembered the motion suddenly—the way you had to let your wrist remember the timing, not your brain. In another, we stood beside a sign we made together for a lemonade stand, the paint crooked and perfect.

“He knew,” Rachel said, and she meant the favoritism, the friction, the way love had been measured out like flour with a cup whose bottom no longer squared with its sides. “He couldn’t change your parents’ hearts. But he tried to build you a bridge.”

I closed the book. “It took me a while,” I said. “But I found the other side.”

There are some stories that want vengeance to be fireworks—loud, brief, glorious, and then a smell in the air that makes dogs nervous. Mine wasn’t that. Mine was the steady work of saying no to the room I had been told to stand in and yes to the door that had always been there. When people online asked me if it felt good to watch the handcuffs click, I told the truth: Justice feels like a clean balance sheet, not a parade. Freedom feels like the quiet after the machine turns off.

On a Saturday in late January, a snowstorm began around noon and made good on itself by evening. I walked to the corner market and bought milk and bread and the expensive butter because a person can decide she’s worth it. On the way home, two kids were making a snow fort and asked if I wanted to help pack the walls. I knelt and showed them how you can use a metal loaf pan for perfect bricks. Their mother laughed from the porch and said, “Where did you learn that?” and I said, “A man who knew about building the right way,” and it felt like both a history and a hope.

That night, I made hot chocolate with the good cocoa, not the grocery store kind that tastes like someone tried to remember chocolate from a dream. I opened the window a sliver and let the cold in to make the warmth honest. Snow powdered the streetlamps. I sent Rachel a photo of the mug and the weather and wrote: No ice storms invented. Only the real kind. She wrote back a snowflake and a heart.

I did not hear from my parents for a long time. When a letter arrived, months into the Denver spring, it was my mother’s handwriting on the envelope. Inside were three pages and no apology. She spoke around consequences like a subway that will not stop at certain stations. She said she hoped that someday we could be a family again. She asked if I might consider calling at the holidays. I folded the letter and placed it in a drawer with my health insurance forms and my lease, things I keep because they exist.

Anna texted once—a blurry photo of a receptionist’s desk with a vase of daisies and a caption that said, “Starting over.” I typed and deleted a dozen responses. I settled on: “I hope you’re well.” It was true. That was what I hoped. Not the performance of contrition, not the optics of humiliation. I wanted her to learn a new measure, to feel the good weight of earning what you keep.

Sometimes justice looks like a courtroom and a ledger. Sometimes it looks like a woman standing alone in her living room in a city she chose, holding a photo of a man who loved her without an audience and saying out loud, to no one and to everyone, “I am not an afterthought.”

Summer came and then the gold of fall that Denver does with such confidence you forget other cities try. I made friends who did not need me to be the quiet one to feel louder. We met for hikes and trivia nights and, once, a trip to a tiny mountain town where the diner still served pie from recipes older than our grandparents. I dated a man who worked in environmental engineering and knew the names of birds; when he told me my laugh sounded like it had decided to stay, I wrote it down so I wouldn’t forget that someone had said it and meant it.

On the anniversary of the Christmas that never happened for me, I woke early, made cinnamon rolls from scratch because I could, and set the table for one with my grandmother’s plate, the one with the thin blue band. I ate slowly, poured a second cup of coffee, and let the radio play low. I texted my grandmother’s neighbor—she’d become my informal update line—and asked her to tell my grandmother I loved her. She sent back a photo of Grandma at the window, pearls on even in her robe, her hand held up like a blessing.

I do not believe pain makes us better. I do not believe forgiveness is a trick we perform to make other people comfortable. I believe in inventories—honest ones, the kind that count what is there and what is not, the kind that name losses and still find a way to say “enough.”

The day I moved to Denver, I pulled off at a rest stop in Kansas and stood under a sky that went all directions at once. I took a deep breath and said out loud, “I’m free.” It sounded smaller than the sky. It sounded exactly right. Freedom, I’ve learned, is like a well‑kept ledger. It doesn’t sing. It balances. It says, with a calm that can look like quiet to outsiders, Here is what I had. Here is what I have. Here is what I deserve to keep.

The year ended, as years do, with people counting down and kissing strangers in bars and promising themselves impossible things. I bought a plant I thought I could keep alive. I learned how to make a perfect omelet every time. I stopped answering questions I didn’t want to answer. I remembered how to draw, a little, alone at my kitchen table after work, pencil smudges on my fingers like I had stolen back a piece of a life. On a page I didn’t mean to keep, I drew a table with space enough for me and wrote underneath it: no invitations required. Then I tore the page out and taped it to the inside of my cabinet door where I keep the good cocoa, a reminder waiting above every cup I make.

On some mornings, Nashville is a far country where a different girl learned hard lessons. On others, it’s a place I pass in my mind like a town off the interstate where you know a good diner and a gas station with clean bathrooms, and that’s enough. I built a life in the same careful way I built that file on my dining table—a tab for work, a tab for friends, a tab for rest, a tab for joy—and I stopped handing the keys to people who don’t know the value of the rooms.

If you want there to be a moral, it’s only this: sometimes the storm is a rumor others tell so they can enjoy their picture without you in it. Sometimes you have to step out into the actually cold air, feel your own breath, and walk toward a weather that will not lie. I did. It was brighter than I expected. It was mine.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load