The night I carried the black gift box with the red ribbon, I parked across from the ballroom and sat for a minute with the engine off, the heater ticking and Sinatra low on the radio from a classic hits station out of Boston. In the cup holder, condensation beaded on a plastic bottle of iced tea I’d grabbed at a gas station off I‑93, the label peeling at the corner the way I peel at thoughts when I’m anxious. My phone screen lit my hands a flat winter blue. In my rearview, the hotel’s glass façade threw back a thousand warm points of light like a chandelier reflected in a lake. When I closed my eyes I could still see the little American flag magnet on my fridge fluttering every time the door slammed, a tiny, noisy thing that never stopped existing just because no one looked at it. Tonight, I felt exactly like that magnet.

“Tonight, I stop being decorative,” I told my reflection, and I meant it.

Inside, the stage was trimmed with the kind of rented elegance my father cultivates like an orchid: fragile, exotic, expensive. A gold goblet at the center of every round table. A soft amber wash against a printed backdrop—WHITLOCK CAPITAL—arched across a stylized skyline of cities he’d conquered and renamed. When the emcee finished his praise and invited the man of the hour to speak, my brothers leaned back like princes in borrowed thrones. My father took the podium and lifted his glass. His smile never reached me.

“I owe it all to my sons,” he said, letting the line breathe for applause. He did not look in my direction. “My daughter never had what it takes.” Laughter rose from people who owed him something and from those who would never risk disagreeing with a legend. Glasses clinked. Cameras flashed. Somewhere a string quartet found the downbeat and went silent all at once.

I stood up. The click of my heels cut through the applause with the satisfaction of scissors finding ribbon. I crossed the distance, placed the small box in his hands, and felt his confusion skim across my knuckles like static. “From your biggest failure,” I said. I kept my voice level, not a tremor in it, not a single cracked note, because I had rehearsed this line the way he rehearsed speeches: in the dark, in the car, in hallways where old portraits listen. Then I turned and walked away.

Out in the corridor the carpet muted everything. I pressed the elevator button and counted the breath between the ding and the doors sliding open. My reflection hovered over the dull brass panels, a smudge over a smudge. I stepped in. The doors shut. Somewhere behind me, across thick glass and a hundred curated smiles, a ribbon would be pulled. Somewhere behind me, a fuse had been lit.

When I was eight, I used to sit on the rug in my father’s home office while he explained the stock market, his voice deep and steady like scripture, a sermon in khaki slacks. He’d let my brothers play with his cufflinks, little silver knots that clicked into place with a magic I wasn’t old enough to copy, but he handed me a calculator like it was a consolation prize. “You’re sharp,” he once said, tapping the screen. “But business isn’t for little girls.” He smiled as if it were a kindness to tell the truth early.

That was the first time I realized love in his world came with a balance sheet, and some of us started in debt. I wrote myself a private note that night—collect.

He believes in rituals: Sunday ties arranged by color, the same barber, the same booth at the steakhouse where the waiters call him sir and laugh as if they’re allowed to. He believes in sons as heirs and daughters as footnotes. I learned early how to make myself useful in the margins. When I spoke, I kept it brief. When I listened, I kept everything.

Graduation came with the cap, the tassel, the Latin that always sounds like victory in marble halls. I stood at a podium of my own as valedictorian while the empty chair in the family row yawned like a mouth refusing to form my name. “Board meeting,” he said when I called. “Non‑negotiable.” The next year, when my brothers launched a company with a logo they sketched on a napkin and a pitch deck full of clouds, he wrote them a check with the kind of flourish reserved for ribbon cuttings. “Investment in potential,” he said. Later that quarter, when the servers failed and the app froze and the website fell into a hole from which even archived copies couldn’t be retrieved, he called it a learning experience. He called it courage. He called it boys being boys.

I called it accounting.

When I joined his firm, the title he offered gleamed like fool’s gold: chief operations assistant. It sounded like the place where trains get scheduled and delays get solved. It was a waiting room with better chairs. Still, I told myself to be grateful—grateful to be inside the building with my name briefly laminated on a badge. I learned the way the elevators hiccuped at floor seventeen and how the cleaners folded the corners of tissue boxes like the Navy folds a flag. I learned his schedule the way you learn a favorite song.

One September night, late enough that the windows mirrored the office back at me, I finished a client report at his desk while he was out of town charming a banker with golf. A folder meant for the board blinked at me from the shared drive—one of those administrative miracles that obeys no written rule and all human nature. I opened it, because I was the one who wrote the policies about not opening what didn’t bear your name. The memo was brief, written in sentences as neat as a judge’s cuff.

Reassign her duties. She’s detail‑oriented but lacks leadership instincts. Keep her busy. Quietly phase her out.

His signature nested at the bottom like a snake that had been there all along, coiled in black ink.

Something in me went still. The stillness wasn’t surrender. It was a new kind of listening.

The next morning I made coffee and smiled through the 9:00 a.m. that bled into the 10:30. I adjusted timelines. I smoothed over a call with a client whose expectations had been oversold by a salesman who called his Rolex a tool. I stayed late and asked no questions. In between, I looked. I traced emails into shadows. I followed account numbers like breadcrumbs left by wolves who don’t believe the forest has other eyes.

It starts small when you’re not supposed to see it: the same vendor name popping up at odd intervals, invoices identical in language and amount, a consulting firm with no website, a mailbox address in Delaware that forwards to a suite in Miami that forwards to a phone that never gets answered by a person. Helios Strategy. A pretty word for the sun and a shadow. Each invoice for 19,500 USD, a number precise enough to feel like a secret handshake.

I printed one and circled it in red. The red looked like ribbon.

At lunch I took a call in the stairwell, the concrete echoing every breath. “You’re chasing wind,” our compliance officer said, gentle, paternal, the tone that says don’t embarrass yourself. “Those are legit.”

“Show me the deliverables,” I said.

“I can’t do that,” he said, and then he did what men do when they are certain of the terrain—they laughed and changed the subject. “How’s your father enjoying the run‑up to retirement?”

“Like a parade,” I said. I hung up and went back to my desk and opened a spreadsheet and started collecting the parade’s confetti one piece at a time.

That night I visited the building’s basement where servers hummed their indifferent lullaby. I was allowed there because I had the kind of badge people assume belongs to someone else. I didn’t take anything. I looked. File trees tell stories to anyone patient enough to hear their grammar. On a backup drive mislabeled with the name of an old project, I found a directory of PDFs that mapped to wire transfers whose subject lines said one thing and whose destinations said another. Islands. Shells. A brother’s name as a beneficial owner on a holding company that owned shares of a subsidiary that sold debt to a fund that our firm advised without disclosing. The kind of circle that completes itself like a ring.

I sent a single anonymous email to a board member with a date and an invoice number. I waited. I sent another to an auditor I knew by the smell of his coffee and the squeak of his loafers. I waited again. Months rolled like marbles across a hardwood floor, each one clicking to a stop somewhere I could predict in my sleep. Little questions appeared at meetings like fruit flies you pretend not to see. A partner said, “Do we have the supporting file on Helios?” Another said, “Remind me who introduced them.” Someone else said nothing, the kind of silence that watches doors.

He raised a glass to his retirement and called it a legacy tour. I called it the part of a play when the audience leans forward because the violins have gone soft and the actor smiles too much to be safe. I called a number in a contact list I had no business owning—the retired SEC examiner who ate eggs at the Silver Diner off Route 1 and read the paper like it personally misprinted his name.

“I can’t tell you what to do,” he said, folding his hands around his coffee. “But there’s a way to do it right.”

“What’s right?” I asked.

“Right,” he said, “is the way that doesn’t splash when it hits.” He slid me a list of addresses as if he were passing me a church program. “Cover letter here. Exhibits here. Timeline here. And if you want this to go fast, you number your attachments the way you number a closing binder. People move when you lift the work from their hands.”

I left three hundred dollars in cash under my saucer for a man who insisted on paying his own bill, and I paid a 7,000 USD retainer to a forensic accountant who pretended not to recognize my last name. I scanned. I labeled. I indexed. I wrote explanations with verbs that don’t tremble—wired, misrepresented, omitted. I didn’t accuse. I matched numbers to dates the way you match footsteps to a cadence you’ve learned by walking alongside it for your entire life.

Every night I went home to my one‑bedroom on the second floor of a triple‑decker and set the box with the red ribbon on my kitchen table to remind me to keep my hands steady. I’d tied it weeks early and untied it twice, once to adjust the knot and once because I wanted to see if my palms would sweat when I touched the flash drive. They did. I retied the ribbon and told the magnet on my fridge what I couldn’t tell anyone else.

“Hold,” I said, because even flags need instruction in storms.

The week of the gala, I ironed a dress the color of clean paper and practiced walking in shoes that turned me into a metronome. I wrote a single line for myself on an index card and tucked it into my clutch even though I already knew it by heart. From your biggest failure. The card wasn’t for forgetting. It was for courage.

My mother called the day before. “You’ll sit at our table,” she said, brisk, efficient, the way she is when she can tell a room is cooling and wants to warm it without lighting a match. “Wear something bright.”

“I’ll be visible,” I said. She laughed as if I’d made a joke. I held the phone away and looked at the ribbon. It gleamed like a boundary.

The gala began with small talk, the economy of favors, the choreography of men affectionately punching each other’s shoulders. “Your father,” someone told me, “is the gold standard.” “Your brothers,” another said, “are cut from the cloth.” “You,” a partner’s wife said softly, lips barely moving over her flute of champagne, “are very brave to work with family.”

“I’m good at my job,” I said, which wasn’t the question but was the only answer I needed.

Onstage he told the story he always tells when the room is expensive: the bootstrap parable, the freshman dorm hustle, the first cold call that turned into a warm handshake that turned into a fund. He smiled at my brothers and my brothers smiled at their reflections in the glass.

“I owe it all to my sons.”

The room applauded on cue. He paused, gifted himself the silence in which a man can do harm with the confidence of a surgeon and not a tremor of doubt. “My daughter never had what it takes.”

I pushed back my chair. I carried the box, set it in his hands, and watched—just for a second—as the red ribbon flashed in the stage lights like something alive. “From your biggest failure,” I said. I turned and walked.

In the corridor, I passed a framed photograph of the flag that hangs over City Hall. The glass over it caught my face and made me a ghost walking through other people’s ceremonies. I pressed the elevator button.

In the lobby the doorman nodded, and I nodded back, and outside in the cold the air was the kind of clean that makes you think of ice in a glass. I crossed the street and sat in my car and turned off Sinatra and waited. The ballroom’s windows were a silent movie. A waiter hurried. A cluster of people leaned. My father opened a box. He saw a flash drive and a folded note titled exactly the way the file inside would be titled: from your biggest failure. He reached for his glasses. He turned toward the side of the stage where the AV tech stood with his laptop open, where a cable snaked like a road to the back of the house.

He put the drive in. He clicked. He found a folder named THEATER and another named LEDGER and another named HELIOS, and he clicked the one labeled in a way he would never forget: LEGACY. I watched his face go the color of printer paper. He dropped something. He walked out of frame. His silhouette moved across the glass and then froze. When people write, “he screamed,” it sounds like melodrama. But there is a sound a person makes when a lifetime of confident steps runs out of floor. You don’t hear it with your ears. You see it in the way a body goes slack in expensive fabric.

Forty‑eight hours later, the first headline broke. Questions, inquiries, sources said, documents reviewed. The board convened at 7:00 a.m. on a Sunday and walked out at 9:12 looking like men who had seen an X‑ray they couldn’t unsee. Phones lit. Lawyers cleared their throats and said words that mean don’t delete, don’t travel, don’t assume. My brothers stopped posting photos of their steaks. My mother’s group chat had nothing to say.

He called me twelve times and left one voicemail that started with my name and ended with the clatter of a desk drawer and a hiss of breath. “You don’t understand what you’ve done,” he said somewhere in the middle.

I did. Perfectly.

I kept going to work. I stapled and signed. I took notes at a meeting where every person spoke as if speaking were a crime. When the subpoenas arrived, a junior associate carried the envelope like it might detonate and then relieved himself of it by placing it on my desk as if the furniture did the choosing. I logged it. I scanned the time stamp with the same calm I use to slice fruit. I sent what was requested to the people who request such things and I copied the person who trains you to never say more than exactly what is asked.

A partner pulled me into an empty conference room where the HVAC thrummed like a jet warming its engines on a winter tarmac. “Tell me,” he said, palms open in that way that makes them look empty and generous. “Did you know?”

“I do my job,” I said.

“Off the record,” he said.

“There’s no such thing,” I said, and left him with his hands cooling in the air between us.

In the hallway, I paused by a shadow box that displayed a ribbon from some charity run we’d sponsored—red, glossy, unfrayed. The glass fogged near my mouth. I remembered the box on my kitchen table and the knot I’d tied and untied. I remembered the memo that said phase her out and the way I learned to stand so still the room forgot I belonged to it.

By the end of the week, security badges had been deactivated in waves you could chart like weather. A receptionist practiced a smile that said I’m new at this. Investors asked questions with less sugar. Our switchboard pinballed anger. Anonymous forums sharpened their knives with facts. Helios Strategy became a name that meant pattern. 19,500 USD became a chant.

I bought my mother a plant and left it on her porch in a clay pot because there are still things daughters do without fanfare. She didn’t open the door. I didn’t knock. I set the pot to the left of the welcome mat where the flag on the coir looks like it’s perpetually catching wind.

On Monday at nine, the board chair asked me to step into an office that had never invited me to sit. “We need continuity,” he said, and looked at me the way a person looks at an unforeseen bridge.

“Continuity,” I said, “is a series of correct choices.”

“We need someone who knows the machine,” he said. “Clean hands.” He didn’t say the words he thought. He didn’t say woman. He didn’t say daughter. He didn’t say your last name is a cautionary tale. He looked at the notepad in front of him as if the script might creep there if he waited.

I took the job. Not his. Not yet. The one that actually runs the thing that people pretend steers itself. The list was long and I had waited my whole life to lift it.

The first day I held the keys, I looped the red ribbon through the ring and knotted it twice. It didn’t fit the aesthetic of men who like brass and navy, and that was the point. I carried my iced tea into the office that had been my father’s and opened the blinds. Across the street, a flag outside a federal building lifted, held, and fell, the way a body breathes when it finally sleeps without flinching.

People ask whether I regret it, as if regret is a receipt you can produce at the register to exchange one life for another. Regret is for people who were given love and lost it. I was never given the chance. What I did was arithmetic. I balanced the books. I took his aphorism—information is power—and declined to misquote it. He spent a lifetime writing himself into the story’s center. I learned the center is wherever you stand when you stop apologizing for it.

There are consequences beyond the headlines—the quiet ones that never get a chyron. The retired secretary who kept a postcard of her grandkids taped inside her drawer and cried at her kitchen table because she’d never seen her name in a letter from a government office. The janitor who stopped me in the lobby to ask if the night crew would still get their holiday bonus because he has a boy who wants a bicycle “with the pegs.” The cafeteria barista with a new tattoo of a lighthouse peeking above her sleeve who said, “You look lighter,” and then blushed because she’d said it out loud. I kept a small notebook—the only ledger I claim wholly as mine—and wrote their names and the things they asked because continuity is not a speech; it’s a list you check and check again.

At the midpoint of everything—after the first wave of coverage and before the first hearing—my father sent me a letter. Real paper. The envelope had my name in his block letters that used to label our lunch bags. Inside, a single sentence filled a page and bled ink where a hand that never shook had started to learn it might. You forgot I made you. I folded it back into the envelope, tied it with a ribbon I no longer needed, and set it in a drawer I open only when I am looking for proof that ghosts prefer sealed rooms.

“Did he really scream?” my brother Caleb asked me once in a stairwell where men go when they want to be off‑stage and still heard.

“I didn’t hear it,” I said, which was true. “I saw it.”

“What do you want?” he asked, the question that always arrives late and expects a discount.

“I want the machine to do what we said it does,” I said. “I want honesty to stop being a press release.”

“You’ll kill him,” he said, and put his head against the concrete like a boy who wants the building to absorb his mistake.

“I’m not touching him,” I said. “I’m touching the numbers.”

He stopped calling. He will start again when the ground cools. That is not cynicism. That is a family habit.

The day the old letters came down from the building—WHITLOCK—workers wore harnesses and concentration. The hiss of their drills was the cleanest music I’ve ever heard. They lifted each piece into a crate lined with gray foam the color of dust. People filmed it the way you film a beloved landmark altered for winter. When the new plaque went up, smaller, plainer, with my name that had spent a lifetime in parentheses standing alone, a woman I didn’t know took off her sunglasses and said, “About time.” I nodded because some applause doesn’t bruise.

In my office that afternoon I opened the drawer where the red ribbon slept and took it out. I wrapped it around a ledger—an actual book from the early days, paper thick as skin—and tied it with a bow that would have made my grandmother proud. It looked like a present for a child who loved numbers. I set it on the shelf behind me where it catches the light around three o’clock and glows like certainty.

The world calls what I did revenge because it needs a word with teeth for a woman who refused to swallow a story written for her. I call it inheritance. Not the money—God knows money is a fog machine if you let it. I inherited his habits and put them to better work. I inherited his sentences and edited them for accuracy. I inherited the machine and tuned it until the vibrations smoothed into a hum you can stand beside without shaking.

At night, when I lock the door and the hallway lights fall into their automatic dim, I look back once. There is always a moment when the red ribbon glows in the dark like a fuse you can choose not to light. That choice is the whole point. I leave the office lighter than when I entered and step into air that tastes like cold water.

Someone will ask again if I regret it. I will tell them again that regret is a luxury for people who were seen and then forgotten. I was invisible and then I wasn’t. That is not tragedy. That is geometry.

The gift box with the red ribbon sits empty in my hall closet among spare bulbs and winter gloves. Sometimes I open the door and look at it the way you look at an old photograph to remind yourself the past had weight and corners. It taught me a trick: that a thing can be both a warning and a promise, a mirror and a window, a ribbon and a seam.

On a quiet Sunday, I took the small American flag magnet off my fridge and set it flat on the table. It didn’t flutter. It didn’t have to. The kitchen window was open to a breeze I didn’t need anymore. I poured iced tea into a glass with a thick base that made a sound like a good decision when it touched wood. I put my finger on the magnet and pressed until it warmed.

“Hold,” I said, out of habit. Then I laughed, because some habits retire gently without a gala.

If you still want a last line that sounds like a verdict, here it is: I did not ruin him. I stopped helping. And when I stopped helping, the story told on itself the way numbers do when you stop asking them to lie. That is the kind of ending that does not clap. It breathes.

I sleep. Better than I ever have.

Sleep didn’t mean stop. It meant I’d finally closed the book on begging for a page and started writing margins into chapters. The morning after that first unbroken night, I dressed in a navy suit that didn’t apologize for its shoulders and walked into a day that had already been arranged by other people for other ends. I rearranged it.

By ten, an email arrived from counsel representing the board requesting an internal briefing. By noon, a summons to a closed‑door session with regulators landed with the precision of winter light at the corner of my desk. I ate an apple while I read both twice. I answered each with a sentence that neither trembled nor bloated. I stapled my notes. I tied my hair back. I untied the red ribbon from the key ring and slipped it into my jacket pocket because I liked knowing that a quiet refusal to forget could live against the lining like a pulse.

At the conference table with the view of the river, the board chair cleared his throat into his fist and kept clearing it until everyone else found their silence. “We will cooperate fully,” he said. “We will need continuity.” His glance found me like a map that kept updating itself no matter how determined you were to fold it back along the old creases.

“You’ll have it,” I said.

“What exactly did you send?” a director asked, lifting his glasses to his forehead like a visor.

“Facts,” I said. “Numbered. Indexed. No adjectives.”

He made a sound that was either relief or heartburn. I slid a folder across the table. Inside were three examples: the 19,500 USD Helios invoices with identical language, a chain of internal emails that assigned oversight to no one in sentences that performed responsibility without possessing it, and a ledger that showed an offshore account masking a transfer to a vehicle where my brother served as beneficial owner.

“We were told these were vetted,” another director said.

“They were admired,” I said. “That isn’t the same thing.”

A clock on the wall hummed. Outside, a flag on the courthouse roof held itself steady against a wind that wanted to have the last word.

“This is the part that matters,” I said, and saw the way every head came up at once as if trained for that bell. “We’re not a victim of a single act. We’re a chorus of small shrugs that added up.”

It became a sentence I would keep handing to rooms that thought they’d heard every flavor of contrition. It became a hinge.

In the closed‑door session at the federal building, the carpet had been chosen for wear and not beauty. The seal on the wall reminded everyone that the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves eventually meet stone. A woman with a legal pad asked for the record my name, my role, the scope of my access. I answered. A man with a pen that clicked as if it were a metronome asked about timelines and custody of documents. I answered again.

“Did you delete anything?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

“Did you embellish?”

“No.”

“Did anyone instruct you to do any of the above?”

“Yes,” I said, and slid the memo across the table where phase her out sat in ink that couldn’t be sanded down. “He instructed me to be invisible. I complied, just not in the way he intended.”

Across the table, someone coughed into a fist the exact way the board chair had, as if institutions train bodies to rhyme.

When I walked back to the office the winter sun was the color of clean paper and the river chopped itself toward the harbor with the commitment of a machine. A barista in our lobby café drew a lighthouse in the foam of my latte and blushed when I smiled because she wasn’t supposed to be an artist on company time. I tipped more than made sense and wrote down her name in my small notebook because continuity is a list you choose to hold yourself to when no one is watching.

By week’s end, the social weather shifted. The club where my father’s picture hung in a corridor learned how quickly brass tarnishes; a manager I’d known since childhood stopped me at the entrance with a kindness that didn’t come with an invoice. “Ms. Whitlock,” he said, “for what it’s worth.” He didn’t finish the sentence because finishing would have been a choice, and he wasn’t paid to choose. In the lobby of our building, a janitor I’d traded nods with for years pulled off a glove to shake my hand with fingers rough from nights that most people prefer not to imagine. “I’ve been here twenty‑nine years,” he said. “People like it when the machine looks shiny. Thank you for fixing the parts that squeak.” Twenty‑nine. I wrote it down. Numbers become anchors when stories try to drift.

At the midpoint, there was a hearing—procedural, preliminary, and still somehow more honest than most celebrations I’d attended under chandeliers. Counsel for the company sat to my left. Counsel for my father sat to my right. He didn’t look at me. He looked at the table like it held a map of an exit he could memorize if only the lines would stop rearranging themselves.

A question came that invited narrative.

“Tell us, in your own words, why you proceeded as you did.”

I kept it short. “Because the numbers asked me to,” I said. “Because every time I tried to sleep, the invoices kept counting themselves.”

The court reporter’s keys clicked like rain on a metal roof. The woman with the legal pad wrote one word—because—and then underlined it. You find out who listens by what they circle.

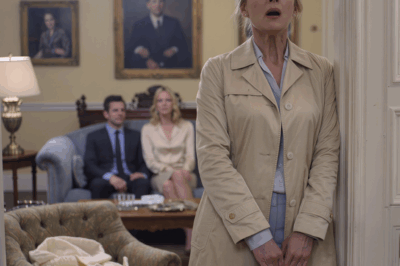

After, in a corridor where the light came from a skylight and made everyone look briefly better than the truth, my mother appeared in a coat I remembered from Christmases when we still bought wrapping paper that matched the tree. She looked smaller, as if the act of walking through official doors had subtracted her confidence.

“Come home,” she said, as if home were a place and not a spreadsheet of loyalties. “We can talk this out.”

“Talking isn’t the same as changing,” I said. “You taught me that when you told me to be gracious in rooms that mistook me for furniture.”

“He’s not well,” she said.

“He was never well,” I said, and heard my voice flatten in a way I didn’t like. I untucked the red ribbon from my pocket and wrapped it twice around my fingers until the circulation sharpened the edges of my patience. “He was effective.”

She studied the ribbon as if it were a new language. “He told me you did this to punish him.”

“I did this to stop helping him,” I said. “He confused my competence with consent.”

She turned her face away and the light from the skylight found a streak of silver in her hair that I hadn’t noticed before. “Your father wrote you a letter,” she said. “You didn’t answer.”

“I read it,” I said. “He said he made me.”

“And didn’t he?” she asked, not baiting, just measuring.

“He made a frame,” I said. “I chose the picture.”

On the subway back to the office, a boy in a Patriot’s hoodie practiced multiplication out loud and his mother nodded like he was reciting a poem. A man in a Red Sox cap dozed with his mouth slightly open. A woman in scrubs checked her phone and smiled in a way that pressed the day’s bad news temporarily into the past. Boston knows how to fold you into its shoulder and keep walking.

The investigation accelerated. That’s how it works when the exhibits are numbered before they arrive. You remove the friction and the machine obliges. Subpoenas. Depositions. A schedule that resisted crisis theater. My brothers stopped calling for a while and then started again with voices that had learned none of the right lessons. “This is Dad’s mess,” Caleb said, which was a sentence structurally incapable of holding the words I signed at the bottom of my very first tax return.

“I didn’t list you as a dependent,” I said.

“What do you want?” he asked, that late question, that discount hunter.

“I want the machine to match the brochure,” I said. “And I want you to learn how to earn a thing without calling it birthright.”

He hung up. The call log looked like a heartbeat that didn’t know whether to run or rest. Twenty‑nine missed calls from numbers that used to come with nicknames. I wrote 29 on the inside cover of my notebook and underlined it twice. Another hinge.

We cut loose Helios Strategy and three other vendors that shared a mailing address with a post office box, an air plant, and nothing else. We repapered disclosures. We replaced a process that asked no one to sign with a rule that asked someone to stop. I met with employees whose jobs would change and handed them timelines that didn’t lie and checks that honored the work they had done under a logo that had been busy flattering itself. On a Friday, we announced an employee fund to cover gaps the headlines never cover—prescriptions, childcare, a tire that bursts when the highway is arrogant. We asked for nothing in exchange. A security guard handed me a note on his way out that said simply my daughter needs braces and I kept the note the way you keep a Polaroid—the edges of the moment intact.

Press calls came like weather. I stood at a lectern that had held my father’s metaphors and refused to borrow any. “We will answer questions,” I said. “We will not speculate.” A reporter asked if our family name would survive. “Names don’t earn,” I said. “People do.” The clip ran on the six o’clock with a lower third that spelled my name correctly and omitted my father’s. It was the smallest, cleanest mercy.

The board asked me to serve as interim CEO. The word interim is a life raft made of qualifiers. I took it anyway and replaced the rope with a rule: independent audit, quarterly town halls where questions could be asked without choreography, an ombuds independent of the org chart, and a policy that forbade off‑site decision meetings at golf courses, steakhouses, or anywhere that required a hostess to smile for a living.

“You’re making enemies,” someone warned, a partner whose cuff showed a monogram like a whisper to himself.

“Only of shortcuts,” I said, and added a line to my list: no policy that depends on someone’s daughter to work.

The night the new plaque arrived, we stayed late. The installers wore harnesses and the concentration of men who trust gravity not at all. They lowered the old letters into a crate while a small cluster of people watched from the sidewalk with the reverent gossip that attaches itself to changes people consider permanent until they aren’t. The new name was smaller by design. It didn’t need to shout. When the protective paper peeled off, the metal caught the streetlight and threw it back without flinching. Someone clapped once. It sounded like a door closing the right way.

I carried the old letters into storage myself because some tasks you delegate and some you shoulder so you remember their weight. The W was heavier than the rest, arrogant even in retirement.

My father requested a meeting. He sent it through counsel and then through my mother and then through a cousin who always thought of himself as Switzerland because he liked the posture of neutrality. I chose the location: the public garden at noon, on a bench within sight of the flag at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, in weather that wouldn’t permit theater.

He arrived in a coat that had never known a winter long enough to humble it. For a moment, I saw the man who taught me to balance a ledger and pronounce EBITDA like a foreign word worth mastering. Then I saw the man who signed his name under phase her out.

“You win,” he said, sitting without asking.

“This isn’t that,” I said.

“What do you call it?”

“An audit,” I said. “A correction. A receipt.”

“You’ve humiliated me,” he said quietly, the hush of a man who has never learned volume for anything but victory.

“I stopped insulating you,” I said. “The rest was gravity.”

He watched a boy sail a paper boat in the shallow water and looked as if he might call out to warn him about drag coefficients. “You will find this lonely,” he said, almost tender, which is to say almost honest. “You will do everything right and still be blamed for the noise the doing makes.”

“I have a list,” I said. “Names. Braces. A lighthouse in foam. A janitor’s twenty‑nine years. The noise is worth it.”

He took off his gloves and placed them on his knees like he was laying down weapons. “I wrote you a letter,” he said. “You didn’t answer.”

“I put it in a drawer,” I said. “Not because I didn’t read it. Because it belongs to a room I don’t live in anymore.”

“You forgot I made you,” he said, and the sentence sounded smaller under the open sky than it had on expensive paper.

“You forgot I watched,” I said.

We sat until the wind reminded both of us that bodies have limits that opinions do not. When he rose, he looked older in a human way rather than in the way of men who are refused deference for the first time and read it as mortality. He held out his hand. I shook it. He waited for a speech I didn’t give. We left without a bow.

Months later, the first court date set itself like a stone in a calendar. My brothers made their arrangements. My mother bought a dress in a color that insisted on optimism. The morning papers printed graphics with arrows and circles and captions that simplified what had never been complicated if you refused to be flattered by jargon. I made oatmeal and ate it at my kitchen table and looked at the empty black box with the red ribbon I kept in the hall closet and felt, for the first time, nothing magnetic tug toward it. It was a thing I had used well. It could retire without a gala.

At work, we closed the Helios loop. Restitution where legally required. Terminations where ethically necessary. Letters to clients that didn’t smuggle excuses inside apologies. A town hall where I stood without a podium and answered until no one had any urgent nouns left. After, an analyst barely old enough to remember the last recession waited until the room cleared and said, “I didn’t know leadership could sound like this.”

“It sounds like complete sentences,” I said. “It sounds like someone willing to say I don’t know and then find out.”

We instituted a rule that every deck begin with a page titled What We Don’t Know Yet. The first time I saw it, the page made a sound inside me I’d last heard when the installers peeled the paper off the new plaque.

Spring pushed the river awake. On a Saturday, I drove out along Route 2 with the windows down and Sinatra traded for silence. In a town where the main street sells antiques the way cities sell ambition, I found a small frame shop and asked for archival glass. I’d brought the little American flag magnet with me. The woman behind the counter asked if I wanted a mat. “No,” I said. “I want it to look exactly like it is.” She smiled as if I’d said something about honesty instead of framing. When I picked it up a week later, the magnet floated under glass like a word in a dictionary that had finally come into use.

On my kitchen table, iced tea sweating on a coaster that didn’t judge, I unwrapped the frame and set it up where the morning light would find it first. I threaded the red ribbon through the key ring again and tightened the knot until it understood that it was ornamental now, not operational. I opened my notebook and beneath 29 wrote another number: 1, the count of mornings I woke up and didn’t reach for proof before coffee.

There are things I will remember when everything else blurs: the weight of the W in my hands; the lighthouse drawn in foam by someone paid to keep the line moving; the way the courthouse flag refused to be impressed by our smallness; the sentence that begins you will find this lonely and fails to account for the ordinary chorus that gathers when you stop performing acceptance. I will remember the first time an employee I’d never met stopped the elevator door with his hand and said, “Thank you for the new policy. My wife works nights. The childcare stipend means I get to see my son in the morning.” Numbers, names, receipts.

On the anniversary of the gala, we sent no invitations. We did not rent violins. At five, the town hall filled with people who had survived a year of learning that transparency is not a synonym for punishment. I spoke for nine minutes and then turned the microphones outward. A partner asked about targets. A receptionist asked about healthcare. A junior lawyer asked about pro bono. The janitor with twenty‑nine years asked for nothing and received applause anyway. When the questions ran out, no one clapped. People gathered their coats and their ordinary hope and went home to make dinner. It was the most flattering ending I could imagine.

I locked my office and turned to go, then looked back at the shelf where the old ledger glowed in its red ribbon at three o’clock even though it was six. Light doesn’t know clocks. It knows angles. I touched the ribbon like a superstition I no longer believed in and let my hand fall.

If you require a verdict, I can give you one that doesn’t pretend to be objective. I did not pull him down. I removed the scaffolding I had been taught to call love. Gravity instructed him. Institutions wrote the last paragraph. I signed the receipt.

I walked out into evening. The city smelled like spring and subway brakes. Across the river, a flag lifted, held, and settled, as if exhaling after reciting something difficult and true. I stood for a minute and let the wind decide which direction my hair would choose. Then I went home and slept, not better than I ever have, but simply—without audit, without the old arithmetic, without rehearsing a sentence for a room that never learned how to hear it.

That is not vengeance. That is the return to balance. That is inheritance, counted clean.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

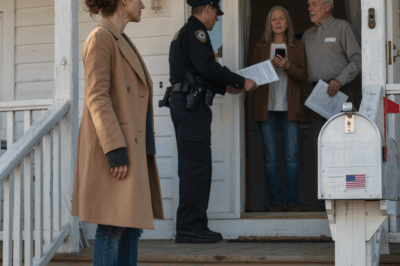

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load