I pulled into my driveway a little after eight, the September air thin and cool, the kind that nips your knuckles when you carry a suitcase in one hand and a coffee you don’t really need in the other. Sinatra still hummed low from the car speakers, the last station I’d had on during the long ride up I‑5 from the redeye into Portland, after two unforgiving weeks at my mother’s bedside in Vancouver, Washington. Inside, the house was dark. No lamp glow in the living room, no low TV murmur, just the refrigerator light casting a pale square on the kitchen tile and catching the edge of the little U.S. flag magnet that usually pins our grocery list to the door. I paused on the threshold with the keys in my palm and heard it: a dull, desperate thumping from below, steady as a metronome, the sound of a house begging to be heard.

There are sounds a home should never make; this was one of them.

“Margaret?” I called into the darkness. My voice sounded wrong, too big, too hopeful. I set the suitcase down and walked fast, then faster, toward the basement door off the hallway. The knob didn’t give. A heavy‑duty padlock hung there I’d never seen before, stitched through a hasp that had no business on the inside of my home. The thumping quickened, and under it a hoarse, shredded sound that might have been a voice. I sprinted to the garage, grabbed the crowbar off the hooks where I keep my tools—civil engineers never quite stop believing in leverage—and jammed the steel into the shackle. One, two, three violent pulls and the lock broke with a bitter crack that rang in my teeth. The door swung inward, and a sour wave hit me: urine, sweat, the particular cold of concrete that hasn’t seen light in too long.

“Thomas?” The voice from below was small and torn at the edges. “Is that really you?”

I took the stairs in two bounding steps, nearly slipping on the wood from moving too fast. Margaret lay at the bottom, curled on a thin blanket that had done nothing against the cold. Her nightgown was torn; her hair was matted to her temples; her lips were so cracked they looked split. She weighed almost nothing when I gathered her up. For a second she didn’t seem to know me, and then she did, and she tried to smile and couldn’t. “I was—” she started, and a cough shook her. I carried her up and set her on the living room couch, the one with the throw she likes, the one that faces the picture window where she watches the crows patrol the street. My hands shook so hard I could barely unlock my phone. I dialed 911 and put it on speaker.

“911, what’s your emergency?”

“My wife,” I said, and heard the raggedness in my own voice. “She’s been—she’s dehydrated, she’s… please, I need an ambulance. She’s been in the basement. Locked in.”

“How long has she been without food or water, sir?”

I looked at Margaret. Her eyes fluttered closed, then open. “I don’t know,” I said. “Two weeks? I’ve been gone two weeks. Please—Harborview, please send someone.”

“Units are on the way. Stay with me. Is she responsive?”

“Yes,” I said. “But she’s weak. She has early‑onset Alzheimer’s. Sixty‑three years old. Please hurry.”

Hinges squealed somewhere in the house from the paramedics arriving felt like mercy arriving.

Red and white washed across the front windows. Two EMTs brought the night and the antiseptic light with them, checked vitals, spoke in calm, exact voices that made room for my panic without letting it expand. “Severely dehydrated,” one said. “Malnourished. Skin’s cold. Sir, when did you last see her?”

“Two weeks ago,” I said. “I was in Vancouver. My mother had a stroke. Our daughter, Jennifer, volunteered to stay. She promised—” The sentence collapsed under its own weight. I swallowed and started again. “She promised she’d keep the routine. The pill organizer. Meals. The shows Margaret likes.”

The EMT met my eyes and didn’t say anything about promises. “We’re taking her to the ER at Harborview,” she said instead. “Do you want to ride along?”

I climbed into the back of the ambulance and held my wife’s hand the whole way, and somewhere on that ten‑minute ride I made a quiet promise no court could enforce but I would: I was going to account for every single minute Margaret spent in the dark and for every single dollar taken from the life we built, and I was going to balance the ledger.

That was the first debt I wrote down in my head.

In the ER, light turned everything unforgiving. They slid Margaret into a bay curtained on two sides and plastic on the third, started fluids, checked labs, wrapped her in warm blankets that looked too thin. A nurse with kind eyes and the brisk competence of someone who has seen everything pulled me aside. “I’m Claire,” she said. “Your wife is stable enough for now. We’ll warm her, hydrate her, monitor electrolytes. I need to ask: has she been confined?”

“For how long?” I asked, even though she hadn’t asked that.

“How long were you gone?”

“Fourteen days,” I said. Saying it made it worse; it made it measurable. “I left at three in the morning two Mondays ago. I called every day for the first week. Jennifer picked up, said Mom was fine. The second week she texted. Then nothing.”

“We’ll notify Adult Protective Services and SPD,” Claire said. “The detectives will want to talk with you tonight. Do you have family we can call?”

“I have a daughter,” I said. “But not tonight.” I looked past Claire toward Margaret’s bay. “My wife knows me. She gets foggy in the evenings, but she knows me.”

“She’ll know you again,” Claire said, not promising, just lending me a sentence to hold onto until someone official came.

Detective Aaron Morrison arrived an hour later in a jacket that had seen too many waiting rooms. He sat across from me with a notebook balanced on a knee and a pen he didn’t seem to notice he was clicking. “Mr. Holloway,” he said, “I’m with the Seattle Police Department’s Vulnerable Adult unit. I need to take a statement.”

“I’m Thomas,” I said. “Sixty‑five. Retired civil engineer. My wife is Margaret. Sixty‑three. Early‑onset Alzheimer’s, diagnosed two years ago. She still cooks with a timer. She still laughs at dumb jokes. We keep the days structured because structure is a kind of kindness with this disease. I left for Vancouver, Washington, when my mother had a stroke. Our daughter Jennifer stayed with Margaret while I was gone.”

“How old is Jennifer?”

“Thirty‑eight. She’s a CPA at a mid‑sized firm downtown. Married to a guy named Kyle who calls himself a business consultant. He talks a lot about crypto and passive income. I’ve never been entirely sure what he does.”

“I’m going to ask this plainly,” Morrison said. “During the time you were away, did you give your daughter power of attorney over your wife’s affairs?”

“No.” The word came out sharper than I meant it to. “Absolutely not.”

“Did your wife sign any documents you’re aware of?”

“Not that I know of.”

Morrison nodded. “We’ll need to look at your house. The basement. Any paperwork. We’ll take photos. If your daughter had access to accounts, we’ll want to know how.” He paused, as if choosing among several hard truths. “Mr. Holloway, if your wife was kept in a basement for fourteen days, that’s unlawful imprisonment. Combined with her condition, that’s elder abuse and financial exploitation if money is involved. I need you to tell me everything you can remember.”

So I did. I told him about the calls that went unanswered in the second week. The texts: Busy with Mom. She’s good. Call you later. I told him about the padlock and the smell and the crowbar and the way my wife tried to smile and couldn’t. I told him about the flag magnet on the refrigerator, because it was the last ordinary thing I remembered before the night turned into something else. He took it all down, his pen no longer clicking.

“Here’s what happens next,” Morrison said when I finally ran out of breath. “We’ll photograph the basement tonight. We’ll secure the door. We’ll collect any electronic devices in plain view. If you have a laptop at home that belongs to your daughter and is on your property, we’ll seize it pending a warrant. We’ll notify APS and coordinate with the King County Prosecutor. There will be a nurse examiner to document your wife’s condition. You focus on her. We’ll focus on the rest.”

It was the first moment I believed I wasn’t alone in this.

Margaret slept under hospital blankets that made a faint papery sound when she breathed. She woke once and asked where Jennifer was. “Making lunch,” she whispered to the ceiling, and then she closed her eyes again. I sat until the fluids finished and the nurse tucked an extra blanket around her feet. Then, while Margaret slept and the machines blinked their indifferent lights, I drove back to the house because Morrison needed me to open the door and because I needed to see with both eyes what my memory kept trying to edit into something kinder.

The basement door gaped like a mouth missing a tooth. The padlock lay on the kitchen counter where I’d dropped it. The smell was worse without my adrenaline; it crawled. In the corner was a bucket, and I didn’t look closely because there are things you owe a person’s dignity, even in your rage. The thin blanket was where I’d found her. There was no light bulb in the overhead socket; someone had unscrewed it. The bare wires looked like a small, deliberate decision.

Upstairs, something else was wrong: our living space had been slightly rearranged by a stranger who knew us too well. The pill organizer that lived on the kitchen counter was gone. The family calendar Margaret used to keep track of days was flipped to the wrong month. There were boxes stacked beneath the window, labeled in my daughter’s neat block letters with things Margaret used daily: throws, books, photos. On the table sat Jennifer’s laptop, lid closed, power light pulsing.

I looked at the front door, at the detective’s card on the hall table, at the laptop again. I’m not proud of what I did next, but I did it, and I’d do it again. The password was saved because convenience makes us sloppy. The desktop held a neat folder tree, and one of those folders was named Estate — Active.

Inside were PDFs. Scanned, notarized, dated within the first week I’d been gone. A power of attorney with Margaret’s shaky but recognizable signature, witnessed by a strip‑mall notary in Tacoma neither of us had ever used. Bank statements from our credit union. A HELOC document we had never signed, new and clean as a crime scene. A spreadsheet labeled Transfer Summary with lines and amounts that tightened the back of my neck as I read: $75,000 — Savings withdrawal; $100,000 — HELOC draw; $175,000 — Wire to Stonehill Capital Management LLC.

Three clicks and a search later, I found Stonehill’s registration: a Washington LLC, formed six months ago. Registered agent: Kyle Morrison. Business description: cryptocurrency investment and blockchain consulting. It sounded like every nothing I’d hoped he was only talk about. The money had gone straight there.

But what turned my hands cold wasn’t the money. It was the texts I found between Jennifer and Kyle. Day Three.

KYLE: She keeps crying for your dad. This isn’t going to work.

JENNIFER: She’ll forget. Give it another day. The confusion helps.

KYLE: What if someone checks on her?

JENNIFER: Who? Dad’s in Vancouver. Mom’s friends haven’t been over in months. We’re fine.

They’d locked a vulnerable woman in a dark room because light might make the truth too obvious.

Some numbers are just numbers until you put them next to oxygen; fourteen became a verdict.

I called Morrison from the kitchen, my voice flat with something that had cooled from panic to purpose. “There are documents,” I said. “Power of attorney. A HELOC. Wire transfers totaling a hundred seventy‑five thousand to Kyle’s company. And texts. They talk about keeping her quiet. They say she’ll forget.”

“Don’t touch anything else,” he said. “I’m on my way.”

By eleven, two officers stood in my living room and another waited by the basement door. Morrison photographed everything. He slid the laptop into an evidence bag and sealed it. “We’ll apply for a warrant first thing in the morning,” he said. “I’ve called the on‑call deputy prosecutor. We’ll flag the banks now. If there are still funds, maybe we can freeze them before they vanish into a wallet we can’t see.”

“What about Jennifer?” I asked. “Where is she?”

“Do you have her current address?”

“South Lake Union. A condo she and Kyle rent. I have the unit number.”

Morrison made a call. Patrol units checked the building within the hour. Jennifer and Kyle weren’t there. The concierge said they hadn’t seen them since late afternoon. What officers did find in the trash chute turned into the kind of proof even a defense attorney hates: bank printouts, a travel itinerary for two one‑way tickets to Lisbon connecting through Heathrow, and an email from a property manager in Portugal confirming a six‑month furnished rental starting Sunday.

If I’d stayed in Vancouver the three extra days I’d planned at the start, Margaret could have died in that basement, and my daughter would have been across an ocean while I was still polishing the words family emergency for people on the phone.

Sometimes you don’t realize you’ve arrived early to your own disaster until the door swings open and you’re the one holding the crowbar.

Harborview discharged Margaret after three days. The doctors warmed her, hydrated her, brought her numbers into the margins of normal and wrote discharge instructions that left no room for error. Adult Protective Services opened a case. A social worker with a gentle voice asked me more questions than I knew the answers to and promised follow‑up home visits. Margaret slept through most of it. Sometimes she woke and asked if Jenny was coming by with lunch. When I couldn’t answer that, she asked, “Did I do something wrong?” and I said “No,” because anything else would have been cruelty dressed as clarity.

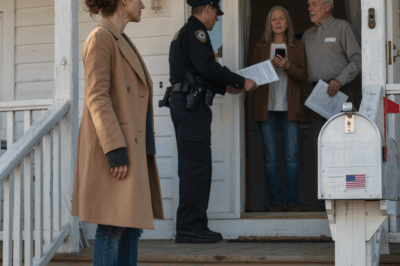

On day six, TSA flagged two passengers at Sea‑Tac who matched the BOLO that had gone out forty‑eight hours earlier: Daughter and son‑in‑law wanted in an elder‑abuse investigation. SPD met them at the gate. Morrison called me within the hour. “We’ve got them,” he said. I stood in my kitchen with the flag magnet holding a new list—discharge meds, daily routine, morning walk—and I felt nothing. Not relief, not triumph. Just empty space where the idea of my daughter used to be.

The charges came like they always do in a set of words that look tidy in print and heavy in a courtroom: unlawful imprisonment, financial exploitation of a vulnerable adult, first‑degree theft, identity theft, forgery. Kyle picked up extra counts tied to Stonehill Capital—securities fraud and theft by deception for a Ponzi he’d been running on thirty other people who trusted the wrong smile and lost savings they didn’t have time to earn again. The King County Prosecutor’s Office assigned an assistant district attorney named Patricia Chen who had a voice like a metronome and a focus that made me think about steel.

“Mr. Holloway,” she said in our first meeting, “we’re pursuing this aggressively. The premeditation is obvious. The vulnerability is obvious. The harm is measurable.”

“How long?” I asked because turning pain into math is how I’ve solved problems my whole life.

“For Jennifer, with the confinement and financial exploitation: eight to twelve years is realistic. For Kyle, with the additional securities fraud: ten to fifteen. We’ll seek restitution for the $175,000, but I want you to prepare for this reality—most of that money is gone.”

“Gone where?” I asked, knowing the answer.

“Offshore accounts, transfers to earlier ‘investors’ to keep the illusion alive, consumption.” Chen folded her hands. “We’ll do what we can to claw back, but the civil remedies will be as important as the criminal ones.”

I hired a lawyer named Christopher Walsh who specialized in elder law and the ruins people make when they forget what family means. He filed a civil complaint two weeks later: Jennifer Holloway and Kyle Morrison, defendants. Conversion. Fraud. Breach of fiduciary duty. Intentional infliction of emotional distress. Damages sought: $175,000 in stolen funds plus $200,000 in additional damages for what Margaret endured. He also drafted a letter to the Washington State Board of Accountancy, documenting how Jennifer had used her credentials as a CPA to lend cover to Stonehill’s lies. Her license was suspended pending the outcome. There are things that don’t feel like victories and still matter; this was one of them.

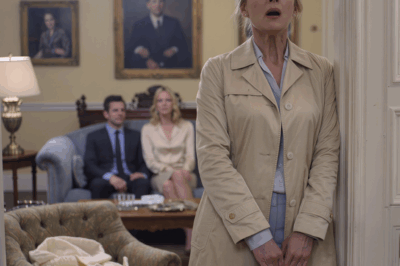

At the bail hearing, I sat in the back row because I could not bear to sit anywhere else. Jennifer’s attorney talked about community ties, about a lifetime without a record, about the supposed influence of an older husband. The prosecutor talked about flight risk, about plane tickets, about a mother confined in a windowless room for fourteen days. The judge denied bail. One sentence, no flourish. The gavel didn’t need to be loud to do its job.

Some doors close for the right reasons and still echo.

The months that followed were administrative and grinding. Margaret’s Alzheimer’s worsened, because stress doesn’t just bend a brain like hers—it cracks it in places you can’t see until you try to remember the way back. We hired a full‑time caregiver named Louisa, who had a way of making everything seem possible. I refinanced the HELOC Stonehill had opened against our will into the mortgage, which meant breaking the pride of twenty years without one, then accepting a monthly payment we hadn’t planned for at sixty‑five. Insurance covered some of Margaret’s care; her neurologist wrote letters that turned heartache into paperwork.

Every few weeks, Morrison would call with an update. The laptop had given them more than they’d hoped: searches Jennifer made for “power of attorney for dementia parent Washington,” “elder exploitation what is it,” “countries without extradition for fraud,” “best time to fly to Lisbon.” There were drafts of fake statements she’d prepared for Stonehill, two co‑workers at her firm who’d invested because Jennifer had said it was safe. Kyle’s investor list read like a cruel census: older, widowed, recent retiree, a veteran with a pension he shouldn’t have touched. Chen added victims to the charging documents. The case got bigger, but for me it stayed the same size—fourteen days in a basement, one number on a spreadsheet that said $175,000, one face I couldn’t reconcile with the child I’d taught to ride a bike on our quiet street.

At the preliminary hearing in January, I testified. I told the court how I found Margaret. I told them about the crowbar and the bucket and the lightbulb that wasn’t there. The defense tried on its narrative: Jennifer was manipulated by Kyle, overwhelmed, trying to help, not thinking clearly. The judge looked over his glasses and quoted the texts. “She’ll forget. Give it another day. The confusion helps.” He bound the case over for trial in June.

Before the trial, Kyle did what men like Kyle do when a mirror gets held up and the room is full of people who can see: he offered a deal. He would plead guilty to all charges and testify against Jennifer in exchange for eight years with eligibility for early release after serving two‑thirds. Chen asked me what I thought.

“Will he go to prison?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “He’ll serve real time.”

“And will this help convict Jennifer?”

“It will make it nearly certain.”

“Take it,” I said, and tasted metal.

Kyle stood up in court in February and said the words guilty. He apologized, and I wondered how long it had taken his attorney to write something that sounded like remorse without costing anything. The judge handed down eight years and didn’t make a speech; he didn’t need to. The sentence said what speeches never can.

The trial in June lasted three weeks. The prosecutors walked the jury through the documents the way an engineer might walk them through a load path—showing where the weight went when the structure failed. The POA signed in Tacoma. The HELOC. The wire. The bank flags. The Lisbon tickets. The condo cleared out. The investor statements Jennifer had faked. The text messages. The video the police had taken in my basement the day they executed the search warrant: the thin blanket, the scratch marks near the door, the socket with no bulb. Two jurors cried. Another one sat with his hands clenched until his knuckles went white and stayed that way.

Margaret testified, and it undid me. She was brave and confused in the same breath. She told the truth in fragments because that’s the only shape truth sometimes takes now. The defense tried to make the confusion mean unreliability. The prosecution turned it into context: this was the very vulnerability exploited.

Jennifer took the stand. She tried to make herself smaller than the choices she made. She said she was trying to help. The cross‑examination was one of those quiet destructions you witness and feel the ghost of afterward. “Miss Holloway,” Chen said, holding a printout, “you texted your husband, ‘She’ll forget. Give it another day. The confusion helps.’ Who were you talking about?” Jennifer stared at the paper. “My mother,” she said. “What were you waiting for her to forget?” Silence can be instruction. The jury learned everything it needed to from that particular quiet.

Deliberations took four hours. Guilty on all counts.

At sentencing two months later, I read a five‑page victim impact statement I’d written at my kitchen table with the flag magnet pinning the first draft to the refrigerator while I crossed out lines that sounded like anger and left in the ones that sounded like accounting. I told the judge about fourteen days. I told her about $175,000. I told her about a house paid off for twenty years and a mortgage we now had again because of paperwork someone else signed. I told her about a wife who asked me who I was for the first time last month and the way that hour felt like someone had swapped my life with a stranger’s and not warned me. Margaret’s neurologist submitted a letter about accelerated decline. The judge listened, and when she spoke to Jennifer she used a tone that wasn’t cruel or forgiving; it was simply exact.

“Miss Holloway,” she said, “you are an educated professional who understood your mother’s vulnerability and exploited it. You planned the timing. You planned the confinement. You planned your departure. This court sees no mitigating factor that excuses that conduct.” Twelve years in state prison. Restitution: $175,000 plus interest. Mandatory no‑contact orders. The gavel was gentle. The sentence was not.

Some math is clean only on paper. In life, there’s residue.

The civil suit ended in a settlement that said, in lawyer language, that Jennifer and Kyle owed us $375,000 and would owe us on any future wages, assets, inheritances, windfalls. It was a line drawn on a horizon. I am an engineer by training; I know horizons are promises you can walk toward forever and never reach. We carry the liens anyway. We make the mortgage payment. We pay Louisa. We keep the routine taped to the refrigerator: morning meds, two eggs, walk to the corner, Sinatra on the smart speaker at eleven because it’s the hour she smiles the most.

Sometimes Margaret asks where our daughter went. On good days I say, “She took a job out of state for a while,” and Margaret nods like the sentence fits a hole her brain needed filled. On harder days she forgets she ever asked. Last month, watching a baseball game we didn’t care about, she looked at me and asked my name. It lasted only an hour, and when it returned to me it felt like a gift I hadn’t earned. But the hour remains in my pocket like a coin I can’t spend.

People ask if I regret pressing charges against my own child. They ask if twelve years is too much. The way they ask suggests the answer they’re braced for is yes. I tell them I made a promise in the back of an ambulance on a Tuesday night, and then I kept it. I tell them fourteen days in the dark is more than twelve years in a place with a sky. I tell them money can be earned again, but time is only spent once. Accountability isn’t revenge. It’s repair, even if the repaired thing bears the seam forever.

I don’t visit. Jennifer is at the women’s correctional facility down in Gig Harbor. Kyle is up at Monroe. They will be eligible for early release after they serve time I count in calendar squares while I help Margaret button cardigans she can’t always understand are hers. Maybe one day they’ll send letters. Maybe one day I’ll read them. Today is not that day.

On Sunday afternoons, I brew iced tea and set the glass down on the kitchen counter, and the ring it makes looks like a clock that has made its peace with circles. I straighten the routine on the refrigerator and slide the flag magnet back to the top when it skates down an inch, because gravity is patient and so am I. We sit at the small table that gets the best light. I read the paper out loud. Margaret watches the crows in the maples across the street and hums along when Sinatra sneaks into the room around eleven. Sometimes she reaches for my hand and squeezes like she’s trying to say everything in one small gesture because words have become expensive. Sometimes I squeeze back, and for the length of that squeeze we’re the same people we were before a padlock taught me what the word daughter can also mean.

I can’t get the smell of that basement out of my head, and I don’t want to, not all the way. Some things you keep to make sure the ledger stays honest. The crowbar is back on its hooks. The laptop is in an evidence locker. The padlock sits in a Ziploc in the back of a drawer I almost never open, a dull piece of metal that weighs far more than it looks. It is not a trophy. It is a reminder that comfort can make you miss the first wrong note.

I still make lists with the mechanical pencil I’ve had since the first freeway project I ever worked on, and when I draw a line through an item it feels like setting a beam true. The list on the fridge today reads: call neurologist, refill meds, pay mortgage, buy more eggs, walk at three, Sinatra at eleven. Under it, in smaller letters, I wrote something I don’t need to but like seeing anyway: keep the promise. The flag magnet holds the list up as if that is the job it trained its whole life to do. It feels too simple to say a magnet can be a symbol, but symbols are just objects that survive long enough to mean more than they did on the day you bought them at a hardware store checkout line.

If you came by the house right now, you’d see a man and a woman at a small table under a sunny window next to a refrigerator door with a list and a small flag holding it steady. You’d see a room where the light is ordinary and therefore miraculous. You wouldn’t hear any banging. The house doesn’t make that sound anymore. And if you asked about justice, I’d tell you about a promise made between a husband and a wife in the back of an ambulance and paid down in hearings and statements and a dozen hinge moments when it would have been easier to let someone else keep count. I’d tell you we are not done paying. I’d tell you we are still here.

Some debts can’t be collected. The trick is to stop pretending they can and collect what’s left: a morning, a song, a walk to the corner, a hand to hold, a list held steady by a cheap little magnet that keeps reminding me what standard I set for myself the night I broke a lock and rewrote the math of my family.

That is the ledger I can live with.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load