I didn’t realize a piece of printer paper could gut a person until the guard at the Briarfield Conservatory tilted his clipboard and I saw the words taped beside his chest: DO NOT LET THESE CHILDREN IN. The black marker letters were thick and certain, the kind of certainty I used to admire in contracts and wedding menus. My son’s hand was small and hot inside mine. My daughter’s lip trembled in a way that took me straight back to the fever nights when she was two and I slept in a rocking chair breathing steam across her forehead because we couldn’t afford a humidifier.

We had driven three hours out of Cincinnati, past bare cornfields and water towers, past billboards offering miracles for the low price of a monthly tithe, past the sudden rise of Columbus like a promise. I’d circled the venue on Google Street View so many times the doorman felt like an acquaintance. I paid for the hydrangeas and the string quartet and the risotto station because my stepsister, Lily, wanted a wedding that felt like a movie. I believed she had earned a scene where everything landed right for once. That was my mistake: believing she and I still wanted the same things when it came to family.

“I’m sorry, ma’am,” the guard said. He couldn’t have been more than twenty-three. He looked like my nephew might one day—wide shoulders, good bones, eyes that can’t hide kindness even in a uniform. “They told us no children. Strict policy. I didn’t… I mean, I don’t make the rules.”

“I know,” I said. “It’s all right.” I smoothed my daughter’s hair. I felt the way mothers feel when they’re trying not to bleed in front of their young. “We won’t be attending.”

The conservatory’s glass panes reflected the winter light in hard squares. It was March. The sun had that cold, biting brightness that makes you think of clean bedsheets and hard truths. Behind the doors I could hear the rehearsal of the quartet—Bach meandering across marble. In a corner of the vestibule, an easel held the seating chart. I had paid extra to have it calligraphed by a woman named Ruth who lived above a bakery and whose emails arrived at two a.m. with photographs of flour-dusted hands holding delicate words in navy ink.

“Is Aunt Lily mad at us?” my son asked when we were back outside.

“No,” I said, my breath steaming white. “She just forgot who helped her.”

We walked away. My heels sounded too loud on the stone walkway, so I took them off. The concrete was cold through my stockings. My car waited at the curb like a friend who didn’t ask questions. I buckled everyone in, then sat for a moment with my hands on the wheel, listening to my heart fight for a normal rhythm.

On the drive home, the kids played a game counting red barns. I tried to imagine how it happened—how a sixteen-year-old girl who had once cried into my shoulder and called me her real mom had become a woman who would write “especially hers” in a message about barring children from a party paid for with their story. I tried to remember what love was supposed to look like when it was exhausted: perhaps that’s the place where pride slips in and starts dressing up as aesthetic.

We passed a farmhouse flying an American flag that had survived real weather; you could see the strain along its stripes. I thought about strain. I thought about the years it took to build a life with stretch in it. I thought about the night before, when I sat in my kitchen with my email open and a folder on my desktop titled “Briarfield.” Screenshots. Transfers. Receipts from my checking account to Lily’s planner. The messages where she laughed about how “trash” my kids would look in the photos. A voice note, careless and bright, bragging about bleeding me dry.

I didn’t write a caption. I didn’t add context. I typed “Daniel Whitaker Family” into the To: field because that was how she’d said it out loud—“The Whitaker family,” like a brand—and pasted in the addresses she’d forwarded me months earlier when I sent a draft of the rehearsal dinner invitation for their review. I attached the documents, wrote “For your awareness,” and clicked send. It was the cleanest sentence I had in me.

By the time we crossed the Ohio River back into our part of town, the kids were sleeping the deep, flung-open sleep of children who have learned something new and don’t yet know where to file it. I carried my daughter inside and covered my son on the couch with the heavy wool blanket my grandmother knit the winter my mother was born. That blanket knows about storms. I brewed coffee because there are griefs that require heat.

The phone rang two hours later. Unknown number. “Is this Mrs. Hail?” a man asked, his voice as precise as a ruler.

“Yes,” I said.

“This is Richard. Daniel’s father.”

I leaned against the counter. “Hello.”

“I wanted you to know the wedding is off,” he said. “My son saw what they did to you. To your children.” There was a pause, the smallest crack of human beyond the steel. “He said he couldn’t marry someone who could humiliate the person who raised her.”

I pictured Daniel—the quiet, decent man who carried boxes without being asked, who sent flowers to my office on Administrative Professionals Day because he said behind every kept appointment there is someone kind. He had always seemed a touch stunned by Lily’s beauty, as if he hadn’t realized you could buy the kind of light that follows a person when she walks through doorways. Maybe he just hadn’t realized that light had to land somewhere. Often it lands on someone else’s back.

“I see,” I said, and traced the lip of my mug the way you trace a familiar coastline. “I’m sorry it happened this way.”

“Me too,” he said. “I’m packing now. We’ll… we’ll take care of what needs taking care of.”

After the call, the house went very quiet. That particular quiet sometimes appears after disaster, like the earth itself is letting its lungs rest. I stood in the kitchen and watched a thread of steam rise straight up from my coffee as if nothing on earth could bend it.

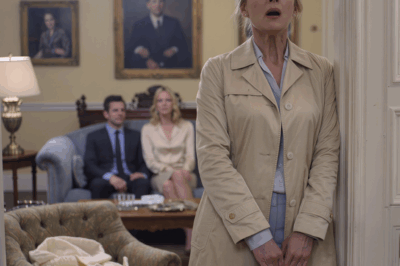

At 7:40 p.m., there came a knock that sounded like someone trying to make the past open. Three sharp wraps. I didn’t move at first. I let the knocks arrive like weather. When I finally walked to the door, I looked through the peephole and saw mascara carved into cheeks, silk collapsed into wrinkles, a girl who used to wear my old cardigans now wearing a dress that cost more than my first car. I opened the door a crack—just enough for her to see my face and the steadiness I had borrowed from every woman in my family.

“You ruined everything,” Lily said. The way her voice broke, I could almost hear the girl she had been—sixteen, scared, hungry, showing me a report card with a C in math and asking if that meant she’d have to work at the gas station forever.

“No,” I said. “You did that yourself.”

“Daniel left,” she whispered. “His parents said I’m disgusting.”

I said nothing. There are some sentences that don’t need an answer; they need an echo and time.

“Please,” she said finally, her mouth small as a child’s. “I have nowhere to go.”

My hand tightened on the door. And there it was again—the image of her at sixteen, elbows like knuckles, eyes like winter. But that girl had learned something I didn’t teach her: that beauty could become currency, and currency could purchase disdain. She had taught my children what cruelty looks like when you iron it and hang it on a hanger called taste.

“You should have thought of that,” I said softly, “before you taught my kids what cruelty looks like.”

I closed the door slowly. The click of the deadbolt felt like a heartbeat finally choosing a rhythm.

The next morning, the sun came up with the clean look of a freshly washed shirt. My kids ran to me smelling like syrup and shampoo, and we made pancakes because I wanted the house to remember sweetness. Not every story requires a monologue at the end where the villain repents and the heroine forgives. Some stories require good coffee and a promise to yourself that the next time someone asks you to set yourself on fire to keep them warm, you’ll hand them a sweater and point to the door.

That would be enough as an ending, but real life has a way of writing epilogues whether you invite them in or not.

The first time I saw Lily she was wearing a jacket four sizes too big and a look that would have buckled a lesser person. My mother had married her father when I was eleven and she was seven. By the time I was twenty-five, our mother was gone—pancreatic cancer quick as wildfire—and Lily’s father had run someplace warm with a woman who wore white sunglasses in November. I had two toddlers and a mortgage shaped like a dare. I took Lily in because that’s what you do when the word family is more than holiday cards.

We were poor in the way that teaches you the exact price of milk. I learned every inch of Kroger. I learned coupons and the circular and how to make a rotisserie chicken turn into soup and then turn into tacos and then turn into a story where everyone at the table believes they’re full. The year Lily turned sixteen, I bought a car with a dent in the door and a cassette player that only played Springsteen’s “The River,” so we learned the river and how it keeps going anyway.

There was a custody hearing in Hamilton County—a Wednesday, fluorescent-lit, a judge with a tidy mustache and a coffee ring on his legal pad. He asked me if I understood the responsibility. I said yes. He asked me if I had help. I lied and said yes again. Outside the courtroom, Lily hugged me like a person who has been holding their breath for a year and finally got to inhale. “You’re my real mom,” she said into my coat. I didn’t correct her. I didn’t know then that the word real has a way of changing shape depending on who is saying it and why.

When Lily got her acceptance letter to state college, she stood in the kitchen with both hands over her mouth. I worked extra shifts at the clinic and sold the last of my mother’s jewelry—nothing heirloom, just the gold she bought for the way it felt on a wrist—and we made it work. I taught Lily how to write a professional email and how to sit on her hands during meetings so you don’t interrupt and how to read a room when you want something the room doesn’t want to give.

She was pretty. Of course she was pretty. But she was also hungry in that American way that makes pretty into a tool. When she met Daniel—at a fundraiser where she checked coats and he checked boxes for a nonprofit—he looked at her like a person who has accidentally walked into a more beautiful life and is trying not to drip soup on the rug. He was decent. Not perfect. But decent counts for a lot in a country where people call charisma a moral quality.

By the time they got engaged, I had paid down the last of my credit card debt from those early years and the house creaked less when the wind hit it. Lily stood in my kitchen—always my kitchen, always the room where the truth has to sit—and cried into my shoulder. “You made this possible,” she said. “I love you more than anyone.” You would have said yes too. When she asked if I could help plan the wedding, I didn’t hesitate. Checks. Calls. The dailiness of a dream. I smiled through exhaustion because that’s what you do for the people you call yours.

If you want to know what love looks like on a spreadsheet, ask a single mother with a mortgage and a sense of duty. I opened a new credit card with a twelve-month promotional rate and named the card in my head after every promise I’d ever made to my mother. The florist was Kendra, a small woman with forearms like a rower and a van that smelled like earth. The calligrapher was Ruth, who lived above a bakery and typed with flour on her fingertips. The quartet was led by a man named Marcus who wore scuffed shoes and took requests with reverence. The caterer was Etta, who took my hand in hers when we signed the contract and said, “We feed people when we love them, and when we love them we want to make it look like art.”

The first sign I missed was literal: a mood board she sent with “no children” on it in the breezy font of people who believe their rules only apply to other people. I wrote back: “We’ll make sure accommodations are comfortable for the whole family!” I wasn’t going to fight with typography. The next sign I didn’t miss. A text she sent the planner that popped up on my screen by accident because her phone auto-filled my name when she meant to send it to someone else. Make sure no children attend, especially hers. They’ll ruin the aesthetic.

I stared at the word hers until it stopped being a pronoun and turned into a weapon. Not my niece and nephew. Not the children of the woman who had paid your rent one May when you called crying. Hers, like something you point at from a distance when it embarrasses you to be seen near it.

I didn’t write back. I didn’t call to ask who she had become. People will tell you who they are if you let them choose, and there’s a particular kind of grief in realizing someone you love prefers the version of themselves they see in strangers’ eyes to the one you’ve known from the inside. I let the grief do its work. I gathered the screenshots without ceremony, the way you might gather the silverware after someone breaks a glass: careful, quiet, efficient.

That night I sent the email. I did not expect an answer. I did not expect an explosion. I expected to have done the only thing a person can do when the truth is heavier than their arms: set it down where it belonged and step away.

After Richard called, a check arrived. The envelope was thick, the paper heavy the way rich paper knows to be heavy. Inside was a note in that same precise hand: We reimburse what you paid. Not because it is equal to what you gave, but because it might keep your kindness from costing your children twice.

I took the check to the bank and sat in my car afterward feeling both relieved and something like shame, because money in your hand doesn’t actually fix the part of a person that says yes too often. I opened two college accounts and deposited most of it there. I bought my son a pair of cleats that didn’t give him blisters and my daughter the paint set with the good brushes, the kind that doesn’t shed.

The next time I saw Daniel it was a week later at the conservatory steps, each of us pretending to be there for reasons that weren’t the same. He looked thinner, like grief had sanded him down. We nodded at each other with the exhausted politeness of people who have been inside a fire and don’t want to talk about the heat.

“I’m sorry,” he said finally. “I should have seen it sooner.”

“Seeing is hard when love keeps fogging your glasses,” I said. Then I surprised us both by smiling. “You’re a good man, Daniel. Be gentle to that fact.”

He almost laughed. “My mother says you’re the only reason I didn’t do a stupid thing and go through with it.”

“Your mother is giving me too much credit,” I said. “You chose.”

He nodded. “I’m going to take some time off. Figure out why I kept thinking beauty could teach kindness instead of the other way around.”

“Good plan,” I said. “It’s easier to start over when you don’t owe anyone an apology for yourself.”

We stood there for a minute in the thin March sunlight, two people who had been orbiting the same star that went out. Then we went our separate ways, each of us a little freer than we had been the day before.

Lily’s messages piled up in the silence like snow that refuses to melt. At first they were sharp, accusing. Then they softened. Then they grew frantic. She changed apartments. She changed jobs. She cut her hair and then let it grow. She dated a man who treated her well, then complained he bored her. She sent pictures of brunch and of dogs that were not hers and of sunsets that looked like everyone’s sunsets.

The world kept giving us ordinary days. I taught my son to tie a tie and my daughter to braid her hair. We planted tomatoes in buckets on the porch and named them like pets. I learned the names of the women at the clinic who cleaned after hours and brought them coffee when the budget said there wasn’t money for raises. I went to bed at ten and woke at six and sometimes woke at three with the kind of old fear that feels like a debt collector knocking on your sternum.

When Lily finally wrote something I could answer, it was because my daughter had asked if people who act mean on purpose can ever learn to be different. We were making a diorama for school—Ohio ecosystems, our river a blue ribbon curling past mud brown—and my daughter held up a crayfish and said, “What if it pinches you and then says sorry? Do you put your hand back in the water?”

“Maybe,” I said. “If the water remembers how to be water and not a mirror.”

That night, I wrote Lily a letter. Not an email. A letter that could be folded and carried and maybe one day open like a small door. I wrote that I loved the girl she had been. I wrote that I could not love her cruelty. I wrote that my children would not be lessons in anyone’s aesthetic. I wrote that if she wanted to see us again, she would need to apologize to them—to look them in the eyes and say the right words, not the clever ones. I wrote that therapy is not a punishment; it is a map. I wrote that I hoped she would find her way to that map.

Weeks went by. Spring leaned toward summer. In June, I opened the mailbox and found an envelope addressed in Lily’s careful hand. Inside was a note with more white space than words. I’m sorry, it read. I forgot who helped me and loved me. I forgot who I was. I want to remember. Can I come by on Sunday at three and say the words to them? I am seeing someone twice a week who is helping me find the right words.

I stood there on the porch where the wind chimes are old and the paint needs another coat and breathed. Forgiveness is complicated when you are a mother. You have to inventory every corner for sharp edges. You have to sharpen yourself against the soft places so you don’t collapse into them and call it grace.

Sunday came bright and hot. Lily arrived on time. She wore no makeup and carried nothing in her hands. She sat on the couch with my children and told them a story about a girl who got lost inside a mirror. She said she was sorry that the girl hurt them while she was looking for the version of herself that strangers praised. She said she was sorry for the sign, for the messages, for the laughter that made other people smaller so she could feel bigger. She cried, and the crying didn’t look pretty. It looked like remembering.

My son asked, “Why did you think we were trash?”

Lily pressed a hand to her mouth. “Because I forgot that the word family doesn’t belong to people who are looking at us from far away,” she said. “It belongs to us.”

My daughter handed her a tissue and said, with the practical mercy of eight-year-olds, “You can sit with us for pancakes if you want.”

We ate. We didn’t declare anything finished. We didn’t declare anything begun. We were just people chewing and passing syrup and talking about whether the tomatoes looked like they needed more sun. After Lily left, I washed the plates and thought about the kind of quiet that arrives not after a disaster but after a decision. The house felt lighter the way a house feels when you open a window and realize the air has been waiting for you to trust it.

That night I made a small list. At the top I wrote: No more bleeding myself dry to keep someone else warm. Under it: No more stories where I am the sponsor and not the family. Under that: Teach my children that walking away is not cowardice; sometimes it is the only way to show a person the shape of what they’re doing.

I taped the list inside the pantry door because that’s where I go when I can’t remember what I promised myself. It is a funny kind of altar, a shelf between the beans and the cereal where old vows live.

You could end the story there. If you need a cleaner ending, there it is. But the world doesn’t care about clean endings. It cares about whether you learned anything.

A month later, I got coffee with Ruth the calligrapher because she was dropping off place cards she couldn’t bear to throw out. “I wrote them at midnight with my window open,” she said, tapping the stack. “The dough proofed while the ink dried.” She held up one card. LILY, in navy like a lake at night. “Sometimes the words look different when you have to write them one at a time.”

I told her about my pantry list and she nodded the way women nod when they recognize a religion they practice too. “Keep it up,” she said. “The world will take every extra inch you offer it and still ask for more.”

Marcus from the quartet called to see if I wanted a refund for the deposit or if I wanted him to play at my kids’ school fundraiser instead. He played Vivaldi next to a bake sale and a raffle basket full of scented candles and made the whole gym smell like redemption.

Kendra the florist brought over the hydrangeas that were meant to sit at the head table. “Flowers don’t care why they get to open,” she said, setting them on my kitchen counter with hands that could braid vines. “They just open because the sun said it’s time.”

Etta, the caterer, donated the food to a shelter and sent me a photo of a man with tired eyes eating risotto like it was his first meal of the year. “We still fed people,” she texted. I cried in my car and then went inside and made grilled cheese, the good kind with butter all the way to the edges.

Daniel sent a letter, a real one, telling me the part of the story I couldn’t have known: the moment his mother opened my email and set down her wine without sipping, the hush at their table as the screenshots made a sound in the air that he said felt like honest glass finally shattering. He wrote that he wasn’t angry at me for sending it. He wrote that he was angry at himself for needing the kind of evidence that hurt to read.

I wrote back and told him the truth no one tells young men: that decent is not a consolation prize. That choosing not to marry someone isn’t proof that you failed at love; sometimes it’s proof that you’re finally learning what love is supposed to do.

A year later, on an ordinary Saturday, I sat in the bleachers at my son’s soccer game and felt the kind of peace that doesn’t perform for anyone. Lily sat beside me. She wore a T-shirt with a stain and didn’t apologize for the stain. She had a job she liked that didn’t require admiration to function. Sometimes she came to therapy and told me about a thing she learned. Sometimes she didn’t. We were not what we had been. We were not what we had pretended to be either. We were something else—something that had learned to live at its true size.

At halftime, my daughter ran up the bleachers and flopped into my lap, all loose limbs and future. “Mom,” she said, “I made a new rule for my life.”

“What is it?” I asked, smoothing her hair that always smells a little like sunshine.

“If someone says I can’t come in because I’m not pretty for their pictures, I’m going to say ‘I’m not a picture.’ Then I’m going to go somewhere else that has pancakes.”

Lily laughed through her nose in the way she used to when she was sixteen and trying not to seem delighted by something. I kissed my daughter’s forehead and said, “That’s a good rule. We can print it and put it on the fridge.”

The ref blew the whistle. The kids ran in a tangle of bright shirts and knees. The sky was the regular kind of blue. I thought about the day at the conservatory—the sign, the guard, the way my heels sounded like a too-loud decision—and I felt my body relax around it. There are stories you don’t get to choose. But you get to choose the last sentence you say aloud to yourself about them.

Mine is this: Sometimes silence is the loudest punishment, and sometimes it is simply the space where you can hear your own life again. Sometimes walking away isn’t revenge; it’s the first step into a room with light that belongs to you. And sometimes—if you are patient and also not patient at all—people will meet you there.

We went home and made pancakes.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

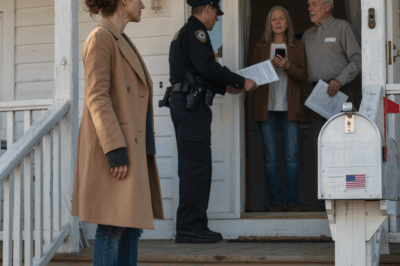

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load