I was holding a chipped ceramic mug with a faded American flag on the side when the notification flashed across my phone.

HEARING DATE CONFIRMED.

SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA.

MARSHALL VS. MARSHALL.

I stood in my small Bay Area kitchen, bare feet on cold tile, the hum of the old refrigerator filling the silence. Outside the window, my little American flag magnet clung crookedly to the metal back door where I’d left it after the Fourth of July. The house smelled like burnt coffee and toast. It was a normal Tuesday.

On the screen, though, it was war.

Some people get sued by corporations. Some by strangers. I got sued by the people who brought me into this world. My parents. And because that apparently wasn’t dramatic enough, the name listed right under theirs was my brother’s.

The kid they told me I existed to support.

That hearing notice was just a few lines of legalese and a date, but to me it felt like a bill for a debt they’d decided I owed since I was fifteen.

The only problem was, I’d already paid.

They just never bothered to notice.

I was fifteen the first time I realized my parents didn’t really see me as their son. Not in the way you’d expect a parent to see their kid. To them, I was a tool, a spare, a fallback plan in case things didn’t work out with their real pride and joy.

My little brother Owen was thirteen then—a bright kid with a loud laugh and a talent for getting exactly what he wanted. Teachers loved him. Neighbors loved him. My parents worshipped him. I used to envy that, the easy affection, the way his name sounded softer coming out of their mouths.

Then I realized the price of being the favorite was never hearing the word “no,” even when you needed to. And the price of being me was being forgotten until there was something heavy to carry.

My name’s Henry Marshall. I’m twenty‑seven now, and I own a two‑bedroom house on the ragged edge of the Bay Area. But this story, this slow‑motion train wreck, really starts twelve years before that, when I packed a single duffel bag, slid out the back door, and walked away from the peeling paint and echoing silence of a house that never really felt like home.

I didn’t leave because I had some grand escape plan. I wasn’t some teen movie protagonist with a map and a soundtrack. I left because I was tired.

Tired of trying.

Tired of pouring effort into a family that only ever filled my cup with guilt and obligation.

I was just a kid with a part‑time job at a gas station off the freeway and a stack of textbooks from the public library. But somehow walking away from everything familiar felt less terrifying than staying.

I didn’t expect to make it. Honestly, part of me assumed I’d come crawling back within a week, that I’d ring the bell with shaking hands and my dad would open the door and say, “Had your little tantrum?” and my mom would roll her eyes but let me in anyway.

I waited for myself to fail.

I never did.

Instead, I slept in shelters, on couches, on benches when I had to. I picked up shifts wherever I could find them—stocking shelves, bussing tables, cleaning offices after hours. I took online classes on borrowed Wi‑Fi in coffee shops until I could afford community college. I kept my head down, worked through summers and weekends, and slowly clawed my way toward something that looked like stability.

I didn’t tell anyone from my old life where I was. I figured they wouldn’t ask.

They didn’t.

Not for a long time.

That’s the part that stings more than I like to admit—not that I left, but that no one came looking. No call. No message. Not even a lazy Facebook DM.

I could’ve been dead in a ditch or halfway across the country and it wouldn’t have disrupted dinner.

I was a ghost the moment I stopped being useful.

Silence can be loud. It says what people are too cowardly to say out loud.

But life kept moving. I got a job in tech after graduation—entry‑level, nothing glamorous—at a startup that later got bought out. I saved everything I could. I wasn’t rich, not by Bay Area standards, but I was okay. I lived modestly. No flashy car, no designer clothes, no bottomless brunches. Just a quiet little two‑bedroom on the edge of town with a mortgage I’d finally paid down enough that the payment didn’t make my stomach clench.

It wasn’t much.

But it was mine.

Every square foot, every light fixture, every screw in the drywall was something I’d earned alone.

That mattered.

Then out of nowhere, they called.

I remember the number flashing on my screen while I was rinsing out that same faded flag mug in the sink. The area code looked familiar, but the actual number was like the ghost of a memory I couldn’t quite place. I let it go to voicemail. I stared at the tiny red notification bubble for a full hour before I worked up the nerve to press play.

“Henry, this is your father. We need to talk. It’s about Owen.”

That was it.

No hello. No “How are you?” Just straight to business.

It had been more than a decade since I’d heard his voice. The first thing he said to me after all that time was, “We need to talk.” Not “We missed you.” Not “We’re sorry.” Not “Are you okay?”

I should’ve deleted the message.

Should’ve blocked the number and gone back to my spreadsheets.

But some pathetic, wounded part of me wanted to know what they could possibly want after all this time.

So I called back.

“Henry,” my dad said, like we’d only paused a conversation for a commercial break. “Glad you called. Look, I’ll get straight to it. Your brother’s going through a rough patch.”

I didn’t say anything. Just let the silence stretch.

“He’s had some setbacks,” he went on. “Dropped out of college, lost his job, couple of bad decisions, nothing serious, but he needs a fresh start. A clean slate.”

My stomach tightened. I already knew where this was going. I could hear it in his tone, that edge of expectation, like a knife being slowly un‑sheathed.

“We know you’ve done well for yourself,” he continued. “Your mother and I talked it over, and we think it’s only fair that you help. Family supports each other, right?”

I almost laughed.

Not because it was funny. Because it was so absurd it felt like a joke.

“You want me to what exactly?” I asked slowly.

“Well, Owen’s staying with us for now, but we were thinking maybe you could give him a portion of what you have. Help him buy a place. Get on his feet. Half, maybe. You’ve got your house, your career. He deserves a chance too.”

I was quiet for a beat too long, and my dad jumped in again.

“It’s not like we’re asking for much,” he said. “Just a fair split. You’re both our sons.”

That word—fair—rang in my ears like a siren.

Fair.

Like it was fair when they told me I was on my own at fifteen.

Like it was fair when Owen got private school and tutoring while I taught myself calculus behind a gas station counter between customers.

Like it was fair when every “We love you” turned into “You should’ve been more like your brother.”

“Dad,” I said, and even I was surprised at how calm my voice sounded. “Are you seriously asking me to give Owen half of everything I’ve built? After everything?”

There was a pause. Then, like he hadn’t heard a word I’d said, he replied, “It’s not just about you, Henry. You owe your brother a future. He’s family.”

That word again.

Family.

As if they hadn’t shredded that concept years ago and left me bleeding on the pavement.

I hung up.

That should’ve been the end of it. Another bizarre phone call to file under “reasons I left.” Another wound to bury.

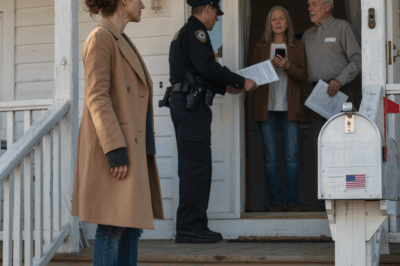

But two weeks later, I got a knock on my front door.

A man in a button‑down shirt and khakis handed me a thick envelope and said, “You’ve been served.”

I opened it at the kitchen table, hands shaking, the faded flag on my mug staring up at me like some kind of joke. The world tilted.

It was a civil claim filed by my parents.

On behalf of Owen, they were suing me.

Their argument was that as his older brother—someone who had “benefited from family support and emotional labor” (I nearly choked on that part)—I was morally and financially obligated to provide my brother with half my assets. They cited “familial expectation,” “unjust enrichment,” and “intentional alienation.”

It would’ve been laughable if it wasn’t so utterly deranged.

But the worst part wasn’t the legal jargon.

It was the attached statement from Owen.

Typed. Signed.

“I believe my brother has a duty to share what he has. Our parents always said we’d be equals. I trusted that. I trusted him.”

As if I’d betrayed him.

As if I owed him anything.

I sat on my back steps for hours after that, the envelope limp in my lap, my coffee gone cold beside me. The little flag magnet on the door rattled every time the wind picked up.

I thought about every night I’d spent hungry. Every graveyard shift I’d picked up to afford books. Every time I’d sat in the back of a lecture hall in secondhand clothes with dollar‑store pens while Owen got new backpacks, new sneakers, and a ride to school every morning.

And now they wanted half.

That was the moment something inside me shifted. Not snapped, exactly—it was more controlled than that. A click, like a lock sliding open.

If they were going to drag me into court and paint me as the villain, I was going to make sure they regretted ever saying my name out loud.

I wasn’t going to yell.

I wasn’t going to beg.

I wasn’t going to explain.

No. I was going to show them exactly who I’d become without them.

And I had a plan.

I just had to wait for the right moment to use it.

The days after the lawsuit felt like wading through molasses. I wasn’t panicking—not outwardly—but I couldn’t focus. My work performance tanked. I stared at my laptop screen for hours without absorbing anything. I barely touched my food. I started checking my locks twice a night, not because I thought they’d show up, but because it felt like they already had.

My sanctuary, my home, the one thing I’d truly earned, was under siege—not by strangers, but by the same people who never noticed when I left.

I didn’t respond to the claim right away. I waited. Watched. Part of me wondered if it was some kind of twisted scare tactic.

Maybe they’d come to their senses.

Maybe they’d realize how insane it sounded.

They didn’t.

A week later, I got another envelope, this time from their attorney—a formal notice of the hearing date, plus “supporting documentation.” Emails. Texts. Photos of our childhood. Report cards. Even a single blurry picture of me standing next to Owen at a backyard barbecue as kids. Like that proved we’d been close.

Like it meant anything.

I read every page.

With every sentence, every manipulative half‑truth, my blood pressure ticked up. They’d rewritten our entire history.

I wasn’t the kid who ran away because no one cared if he stayed.

I was the “ungrateful son” who “cut off contact without explanation.”

Owen wasn’t the golden child who coasted through life.

He was the “misguided little brother who always looked up to Henry.”

My parents—this was the worst part—were portrayed as saints. Heartbroken. Always hoping I’d come home. Always waiting with open arms.

They never once tried to find me.

Never once asked why I left.

Never once reached out.

Not until it became convenient.

It wasn’t just insulting.

It was dangerous.

They weren’t just twisting the truth; they were weaponizing it.

So I fought back the only way I knew how.

I wrote.

At first, it was just notes in a spiral notebook—dates, addresses, memories. Then it became a journal. Page after page of real moments, sharp and painful, stitched together like evidence.

Like the time I asked for new shoes in ninth grade because mine had holes. My mom looked at the soles and said, “Maybe if you didn’t drag your feet, they’d last longer.” Three days later, they bought Owen a pair of Jordans for doing well on a math quiz.

Or my sixteenth birthday. I’d saved up to buy myself a small ice cream cake and left it in the freezer, planning to eat it after my shift. I came home to find half of it gone, Owen’s name carved into the frosting in big messy letters.

“I thought you bought it for the family,” my mom said with a shrug when I asked. “It’s not a big deal.”

Except it was.

Every little thing added up.

Every dismissal, every shrug, every time they made me feel like an afterthought—it had all been groundwork for this moment.

Now that I was no longer a quiet, invisible kid but a man with something they wanted, they were rewriting it all.

That realization—not the lawsuit—was the breaking point.

They still didn’t see me.

They saw what I had.

Not how I’d gotten it.

That’s when I decided I wouldn’t just defend myself.

I was going to dismantle them.

Not physically. Not with screaming matches or dramatic confrontations on their front lawn.

With the truth.

That night, I opened my laptop, pulled up the school district website, and typed in a name I hadn’t thought about in years.

Ms. Linda Carter.

My high school guidance counselor.

She’d been the only adult who believed me when I said things weren’t right at home. The one who pulled strings to get me meal vouchers when I was couch‑surfing. Who quietly slipped me bus passes. Who printed college applications for me behind the library desk and let me use the office phone to call shelters.

I found her email and stared at the blank message box for a long time.

Then I wrote.

I told her who I was. What had happened. What my parents were claiming.

I hit send and honestly expected it to disappear into the void.

Two days later, I got a reply.

“Henry, I never forgot about you. Call me.”

We spoke for an hour.

By the end of that call, she’d agreed to write a sworn statement for the court.

She remembered everything.

The times she tried to contact my parents and they brushed her off.

The teachers who pooled money to buy me a cap and gown for graduation.

The day she found me asleep in the school supply closet because I didn’t have anywhere else to go.

It wasn’t just a character reference.

It was proof.

Proof they hadn’t supported me.

Proof I’d done this alone.

For the first time since that first envelope hit my porch, I felt like I could breathe.

Of course, the universe wasn’t done.

A week before the hearing, I got an unexpected visit.

From Owen.

He showed up unannounced, his beat‑up car parked crookedly at the curb, wearing joggers, a designer hoodie, and sneakers that probably cost more than my first month’s rent on that roach‑infested studio I had at nineteen.

He had the same crooked smile he’d had as a kid—the one that used to mean “I’m about to get away with something.”

“Hey, man,” he said when I opened the door, like we talked all the time. “Can we talk?”

I didn’t open the door fully. I leaned against the frame.

“What do you want?”

He stuffed his hands in his pockets. “Look, I know the lawsuit’s kind of intense. But it’s not personal. Mom and Dad just think it’s the right thing. You know how they are.”

“Unfortunately, I do,” I said.

He sighed. “I’m not trying to take your life or anything. I just need a leg up. A clean slate. I messed up, yeah, but you’ve got so much. I mean, come on. This place, your job… you probably make six figures.”

It was the way he said it. Like it was all handed to me.

“Let me ask you something,” I said quietly. “Where were you when I was sleeping in a shelter on Mission and Eighth? When I was walking six miles to class because I couldn’t afford the bus?”

His eyebrows furrowed. “I… I didn’t know about any of that.”

“Exactly,” I said. “Because you never asked.”

He shifted. “Okay, but still. You’re in a position to help. Isn’t that what family does?”

There it was. The script.

Only now it was coming out of his mouth instead of my parents’.

“I did help you,” I said. “By leaving. By not dragging you down with me. By surviving without ever asking you for a single thing.”

He stared at me, eyes flat. “You really think you’re better than us now, huh?”

I didn’t answer.

Because in that moment, I didn’t know if “better” was the right word.

But I knew I was different.

I’d chosen a harder path, walked it alone, and I wasn’t about to apologize for where it led me.

He left without a handshake, without a hug. Just a bitter look over his shoulder and the slam of a car door.

A few days later, I got the final pre‑hearing packet from their lawyer. They’d doubled down. Added a new affidavit from my parents, full of lies and dramatic flourishes about how “emotionally unstable” I’d been as a teen, how I’d “severed ties out of jealousy,” how I was “punishing Owen for having the support” I never did.

I should’ve been furious.

Instead, I felt weirdly calm.

Because now I understood.

They weren’t just telling a different version of the story.

They were betting on the court seeing me the same way they always had:

As a problem.

As a burden.

As someone they could frame, control, and dismiss.

So I opened a blank document.

And I started writing my final statement.

The one I’d read in court.

The one that would make my parents’ faces go pale and make my brother refuse to look me in the eye.

And as I typed, I made myself a promise:

If they wanted a performance, I’d give them one they’d never forget.

Writing that statement forced me to dig up things I’d buried deep just to keep moving. It wasn’t just legal prep.

It was surgery without anesthesia.

Memories came back in sharp, unwelcome flashes: the sound of my dad’s boots on the stairs when he was in a bad mood; the way my mom’s face pinched when she looked at my report cards compared to Owen’s; the night I sat on the curb outside our house with a torn backpack and a bloody lip, listening to them argue about whether I was “acting out for attention” or just “ungrateful.”

I wasn’t okay.

Not for a while.

I stopped sleeping. My appetite tanked. I’d sit at my desk staring at spreadsheets until the numbers blurred, then shut my laptop and just sit in the dark.

One night, I caught my reflection in the bathroom mirror and barely recognized the pale, hollow‑eyed guy staring back.

“You’re not going back there,” I whispered to myself. “You’re not.”

It felt like a lie.

Emotionally, I was already back.

The lawsuit wasn’t just about money.

It was my childhood on trial.

And I didn’t have a family behind me.

No Sunday dinners. No concerned aunt willing to testify. No warm cousin ready to pick up the phone.

Just me.

Again.

I called a therapist. The earliest appointment they had was four weeks out.

I thought about canceling.

Didn’t.

Instead, I drove to the park near my old community college. Sat on the same worn bench where I used to eat cheap instant noodles during lunch breaks when I had twenty bucks in my checking account and a cracked iPhone held together with tape.

Students hurried past with backpacks and earbuds, stress and ambition written all over their faces.

For the first time in a long time, I didn’t feel envy.

I felt… proud.

I’d been there. Worse than there. And I’d made it out anyway.

That was a hinge moment.

The first time I looked at my life and thought, Maybe I’m not just the kid they left behind.

A few days later, a letter showed up in my mailbox. A real one. Stamped. Handwritten.

It was from Ms. Carter.

She’d enclosed a copy of the statement she was submitting to the court, but that wasn’t what hit me hardest.

At the bottom, in looping cursive, she’d written:

“You were always more than they could see. Don’t let them shrink your worth just because they couldn’t grow theirs.”

I read that sentence four times.

Then I walked into the kitchen, grabbed a magnet—the same little American flag one from the back door—and stuck the letter to my fridge right next to a faded photo of me at my college graduation, wearing a borrowed cap and a paper‑thin gown that didn’t quite fit.

That picture used to make me feel hollow.

Now it felt like proof.

I existed.

And I mattered.

I dusted off my résumé that night. Not because I wanted a new job, but because I needed to see it laid out in black and white.

Every promotion.

Every project.

Every risk.

Every step that had nothing to do with my parents.

I realized I’d become someone.

Someone they didn’t know at all.

To them, I was still Henry the “difficult one,” Henry the “dropout,” Henry the “selfish runaway.”

But that wasn’t me anymore.

I was Henry Marshall, senior product manager at a mid‑sized tech firm. Homeowner. Debt‑free. Mentor to three interns. Volunteer at a local adult‑literacy nonprofit.

A man with a future he’d built out of scraps.

No lawsuit was going to take that away.

Once I remembered that, something shifted.

I stopped reacting.

Started planning.

I hired a lawyer. Not some billboard‑famous shark, just a sharp woman referred by a coworker—a family‑law attorney named Rani who’d spent a decade batting down frivolous cases.

After I laid out my story, she sat back, eyes narrowed.

“This is disgusting,” she said finally. “But don’t worry. We’re not just going to defend. We’re going to dismantle.”

She helped me refine my statement. We combed through every claim in their filing and built a binder of counter‑evidence.

Bank records from when I was fifteen.

Pay stubs from my first jobs.

Rental agreements from every apartment I’d ever lived in.

Photos of me working graveyard shifts.

Screenshots of message threads—or the lack of them.

We even tracked down my old shelter roommate, Marcus. He was working maintenance at a hospital now. When I explained what was happening, he didn’t hesitate.

“I remember you,” he said over the phone. “You used to fall asleep with your face on the textbook.”

He wrote a statement, too.

It felt like assembling an army of ghosts.

Pieces of my past rising to stand beside me.

The biggest surprise came from my old landlord, Mr. Valdez, the man who’d rented me that tiny studio at nineteen. I reached out half expecting him not to remember me.

He remembered.

And he still had a copy of the handwritten thank‑you note I’d left when I moved out.

“He pay on time,” he wrote in his affidavit. “Fix toilet himself. Quiet. Good heart.”

I laughed when I read it.

Then I cried.

Because somehow that mattered more than all the shiny job titles.

That was who I was.

Not the villain in my parents’ story.

As the court date crept closer, I started sleeping again. Eating again. I went back to the gym. A few coworkers commented that I seemed lighter.

“Just cleaning house,” I told them.

They didn’t know what I meant.

But I did.

The day before the hearing, I took off work and drove out to a lake on the edge of town. It wasn’t anything special, just a quiet place with weeping willows and a creaky dock.

I used to go there in college when my apartment felt too suffocating to breathe.

I stood at the end of the dock and pulled a folded, worn piece of notebook paper from my pocket.

It was the letter I’d written the night I left home at fifteen. I’d carried it with me for twelve years. Never showed it to anyone.

It was angry. Messy. Full of scratched‑out curses and jagged lines.

But it was honest.

I read it one last time.

Then I let it fall into the water.

The ink bled instantly. The paper softened, curled, and slowly sank.

It didn’t fix anything.

Didn’t magically heal old wounds.

But it felt like permission.

Permission to stop carrying guilt that wasn’t mine.

Permission to stop explaining myself to people who never listened.

Permission to stop waiting for an apology that was never coming.

The next morning, I woke up early, showered, shaved, and put on the navy suit I’d worn to my first tech conference.

Not to impress anyone.

To remind myself who I was walking into that courtroom as.

I looked in the mirror, adjusted my tie, and whispered, “Let’s end this.”

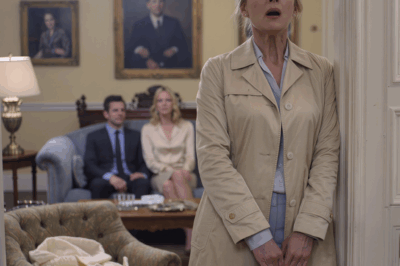

The courtroom was smaller than I expected. No dramatic soaring ceilings like on TV. Just beige walls, worn wooden benches, a raised platform where the judge sat, and a quiet shuffle of papers.

My parents sat at one table.

Owen sat beside them, looking bored, like this was a minor errand between brunch and whatever came next.

Their attorney—a smug guy with slicked‑back hair and an expensive suit—nodded at me like we were in on some private joke.

I took my place at the other table.

Alone.

No family behind me. No friends in the gallery. Just my lawyer, my binder, and the weight of twelve years.

The judge, a middle‑aged woman with tired eyes and sharp posture, called the case.

They presented first.

Their lawyer talked about “moral obligations” and “family expectations.” He said phrases like “unjust enrichment” and “shared upbringing” with a straight face. My mom dabbed her eyes. My dad shook his head sadly at all the right moments.

Owen stared straight ahead.

When they were done, the judge turned to our table.

“Mr. Marshall,” she said. “Have you prepared a closing statement?”

I stood up.

My hands were steady.

“Yes, Your Honor,” I said. “I have.”

The room went quiet in a way that wasn’t accidental.

I didn’t shout.

I didn’t pace.

I didn’t try to imitate something I’d seen on a legal drama.

I just stood there, hands resting lightly on the table, and spoke clearly.

“My name is Henry Marshall,” I began. “I’m twenty‑seven years old. I own a home. I have a steady job, no criminal record, and zero debt. I pay my taxes. I donate to the food bank down the street. And every holiday season, I go back to the shelter I used to sleep in and drop off blankets.”

I glanced at my parents.

Owen shifted in his seat.

“I say all that not to impress you,” I continued, turning back to the judge, “but because I need to establish something that’s apparently been lost in all this paperwork:

I built this life alone.

I wasn’t handed it. I didn’t inherit it. There was no college fund. No co‑signed loan from a generous parent. No financial safety net. Everything I have, I earned.”

My voice didn’t shake.

“But that’s not what this case is really about,” I said. “This isn’t about fairness. It isn’t about family. It’s about control. About a family that ignored me for over a decade until they realized I had something they wanted.”

I picked up the first document from the binder.

“This is a statement from Ms. Linda Carter, my high school guidance counselor,” I said. “She testifies that I was effectively homeless at fifteen. That my parents were unresponsive when contacted about my welfare. That I survived on free lunch vouchers and secondhand clothes from school donations.”

I set it down and lifted another.

“This is from Mr. Stanley Valdez, my former landlord. He confirms that I worked three jobs to pay rent on a two‑hundred‑square‑foot apartment with no heat. That I fixed the plumbing myself because I couldn’t afford a repairman.”

Another page.

“This is from George Peters, who ran the community shelter where I lived for three months. He remembers me coming home from work with cracked hands and study guides, falling asleep at the dining table because I had midterms the next morning.”

I felt Owen’s eyes on me.

I looked right back at him as I held up the last document.

“And this,” I said softly, “is the receipt from the day I bought my house. I paid the down payment myself. Signed the contract alone. No gifts. No loans. Just years of labor and a credit score I built inch by inch.”

The silence in the room changed.

It wasn’t bored anymore.

It was electric.

The judge’s expression shifted, just slightly. My lawyer stayed utterly still, letting the words do their work.

I could have stopped there.

That would’ve been enough to win.

But I wasn’t aiming for “enough.”

“You know what’s funny?” I asked, my tone calm. “Not once, in the twelve years I’ve been gone, did anyone at that table ask how I was doing. No calls. No letters. Not even a birthday text. But the moment Owen needed a house, suddenly I’m ‘family’ again.”

My father’s jaw tightened.

My mother’s mouth flattened into a hard line.

“I’m not angry that I wasn’t helped,” I said. “That’s life. You play the hand you’re dealt. What I’m angry about is the rewriting of history. The idea that I owe something to people who never even acknowledged my pain, let alone tried to ease it.”

I let that sit for a beat.

Then I folded the pages, slid them back into the binder, and looked the judge in the eye.

“I respectfully ask that this lawsuit be dismissed with prejudice,” I said. “Not because I think I’m better than them. But because I refuse to let the people who left me behind profit from my survival.”

The judge looked at me for a long moment.

“Thank you, Mr. Marshall,” she said finally.

Just like that, it was over.

At least, that part.

The judge ruled in my favor. The claim was dismissed with prejudice. No division of assets. No obligation to give Owen a single cent.

I should’ve walked out feeling triumphant.

I didn’t.

I felt hollow.

Like I’d spent months preparing for war and only just realized I was still bleeding from battles I’d never treated.

As I gathered my papers, my parents didn’t come near me.

They didn’t look at me.

But Owen stood by the exit, hands shoved into his pockets, eyes on the floor.

When I passed him, he muttered, “You didn’t have to do that.”

I stopped.

“Didn’t have to do what?” I asked. “Defend myself from being sued by my own family?”

His jaw clenched. “You made me look like a fool.”

I held his gaze. “No, Owen,” I said quietly. “You made yourself look like a fool. I just stopped covering for you.”

I left the courthouse believing that was the end.

That they’d slink off, licking their wounds.

Three days later, I got an email from their attorney.

A single line jumped out:

“Please be advised your family intends to appeal.”

I stared at the screen for a long time.

Then I laughed.

Not bitterly.

Not hysterically.

Just… laughed.

Because it was absurd.

They were still digging.

Still convinced they could twist the system into forcing me to bankroll my brother’s “fresh start.”

That’s when I understood something important:

Defending myself wasn’t enough.

If I wanted this to end, really end, I needed leverage.

So I made a list.

Not a revenge list.

A list of loose threads.

Debts my parents had mentioned and then gone suspiciously quiet about.

Conversations I’d overheard about “fixing the credit” and “rolling things over.”

The time my mom complained about a “cosigner who flaked,” then mysteriously never brought it up again.

I started digging.

Public records. Online databases. Old emails. Credit reports.

And slowly, something ugly took shape.

Turns out my parents had taken out a second mortgage years ago.

One they defaulted on and quietly rolled into a consolidation loan under my mother’s name.

A loan that, thanks to a forged set of initials and some lazy oversight, listed me as a co‑signer.

I had no idea.

I was seventeen.

That alone could’ve blown the case wide open.

But it didn’t stop there.

Owen’s “rough patch” wasn’t new. He’d burned through three jobs in two years. Been evicted from two apartments. Had multiple credit cards maxed out under his name—and at least one as an authorized user on our dad’s account.

I started compiling everything.

Printouts.

Spreadsheets.

Loan documents.

Weird little notations that finally made sense.

Then I sat down with Rani.

When I slid the folder across her desk, she flipped through it slowly, her expression going from curious to cold.

“We’re filing a counterclaim,” she said. “Today.”

We did.

Financial fraud. Identity theft. Restitution.

But we didn’t serve it right away.

Timing is everything.

While the paperwork wound through the system, I sent an anonymous tip to a local financial‑ethics blog about a “possible case of parental financial fraud involving a forged co‑signer.” No names. No specifics. Just enough to pique interest.

I booked a consultation with a forensic accountant.

Reached out to Ms. Carter again.

“You don’t have to become them to get justice,” she told me. “But you do have to be strategic.”

So I was.

By the time the appeal hearing rolled around, everything was in place.

The morning of the appeal, I woke up before my alarm.

I felt… calm.

Not the brittle, fake calm I’d worn like armor.

Quiet certainty.

I put on the same navy suit. Straightened my cuffs. Smoothed my tie.

This time, I wasn’t dressing to defend what I had.

I was dressing to take back what they’d tried to steal.

Rani met me on the courthouse steps, a sleek black folder in her hands.

“Everything’s in here,” she said. “We’ve confirmed the forged signature. The counterclaim is active. Judge Peters reviewed it in pre‑hearing.”

“And the journalist?” I asked.

She smiled, just a little. “Two rows behind your mother. Front‑row seat.”

Inside, the courtroom looked exactly the same.

But it didn’t feel the same.

Last time, I’d felt like prey.

This time, I felt like the one holding the trap door lever.

My parents walked in first, Owen trailing behind. Their original lawyer was gone. They’d lost him the second our fraud claim hit. Apparently, he didn’t do financial crime.

Their new representation was a tired‑looking public defender who seemed like he’d skimmed the file in the hallway.

Owen didn’t look at me.

My father looked irritated.

My mother looked—for the first time—scared.

The judge called the room to order.

Their side started in on why the original ruling was “unfair” and “failed to consider the emotional bonds of family.”

Rani waited.

When it was our turn, she rose smoothly.

“Your Honor,” she said, “before we address the merits of the appeal, we’d like to introduce newly uncovered evidence that directly pertains to the nature of this family’s financial entanglements.”

She handed the black folder to the clerk, who passed it to the judge.

“Mr. Henry Marshall was fraudulently listed as a co‑signer on a high‑risk consolidation loan at the age of seventeen,” she continued. “This action was facilitated by his parents without his knowledge or legal consent. The loan subsequently went into default.”

The judge’s eyes flicked up.

“We have included the loan documents, expert handwriting analysis, and a notarized affidavit from the bank manager confirming the initials were not written by Mr. Marshall,” Rani said. “We are submitting a counterclaim of financial fraud and identity theft under Section 530.5 of the Penal Code, as well as evidence of additional unauthorized accounts opened using Mr. Marshall’s information.”

The air in the room changed.

My father turned to my mother, whispering harshly.

Her hands trembled.

Owen finally looked at me.

I didn’t gloat.

I didn’t smirk.

I just met his eyes, calm.

Because this wasn’t about revenge anymore.

It was about truth.

“And have criminal charges been filed?” the judge asked.

“Not yet,” Rani replied. “The district attorney’s office has been informed. We prefer to resolve this civilly, but my client is prepared to proceed otherwise.”

My parents’ new lawyer scrambled to his feet.

“Your Honor, we—we were unaware of these details. We respectfully request a continuance—”

“Denied,” the judge said sharply. “You filed an appeal arguing that this court failed to understand ‘familial obligation.’ I am now learning that this family engaged in active financial deception against the very son they are suing.”

She turned her full attention on my parents.

“Did you, or did you not, list your son as a co‑signer on a loan without his knowledge?”

My mother opened her mouth.

Closed it.

My father stared at the table.

“I’ll take that as a yes,” the judge said.

Her gavel cracked against the wood.

“This appeal is denied with prejudice,” she said. “Mr. Marshall’s counterclaim will proceed to arbitration within thirty days. Furthermore, I am referring this matter to the district attorney’s office for review.”

Court adjourned.

She stood and left before anyone could say a word.

It was done.

The journalist got the story out within the week.

Names were redacted. Details blurred. But anyone who knew my family could do the math.

The comments under the article were vicious.

“Imagine suing your own kid after forging his name on a loan.”

“They sound like leeches.”

“Glad the judge saw through the BS.”

I didn’t reply.

Didn’t need to.

The legal fallout was quietly brutal.

The fraud finding triggered a freeze on my parents’ bank accounts while arbitration moved forward. They were forced to provide full financial disclosures—every loan, every line of credit, every account that had ever touched my name.

In the end, arbitration ordered them to pay $134,000.

Damages. Legal fees. The full balance of the fraudulent loan.

I could have pushed for criminal charges.

Rani said the DA would have a strong case.

I thought about it.

Then I said no.

I didn’t need them in prison.

I needed them to live in the mess they’d made.

I heard, through the grapevine, that they had to sell their house to cover the judgment. That they moved in with an uncle two towns over. That once he heard the full story, he asked them to leave.

As for Owen, he tried to distance himself immediately.

He sent me an email a few days after arbitration.

He said he hadn’t known about the forged loan.

That he’d “never meant for things to go that far.”

That he was “just trying to get his life together.”

I didn’t respond.

Because maybe he hadn’t known the specifics.

But he knew who raised him.

He knew what they were capable of.

He chose to ride their train anyway.

Right up until it derailed.

A mutual friend later sent me a screenshot.

Owen had applied for a job at a local tech firm. The hiring manager Googled him and found the blog article.

His application was rejected.

The last message on the thread from Owen read, “I think my brother blacklisted me.”

I didn’t.

I didn’t have to.

He’d blacklisted himself.

A few months after everything wrapped up, I packed up my little two‑bedroom and moved.

Not out of fear.

Out of choice.

I bought a small cabin in the mountains a couple hours away. Nothing fancy—creaky floors, temperamental pipes, a wood stove that smoked if you looked at it wrong.

But when I signed the papers, it felt like more than real estate.

It felt like closing a chapter.

I kept my job, working remote most days. Still mentored interns. Still donated blankets to the shelter every winter.

I also started writing.

Not legal statements.

Not revenge emails.

Stories.

Essays about what it meant to grow up unseen. About building a life from scrap wood and duct tape. About choosing to walk away even when no one holds the door.

Some pieces got published. Some lived quietly on my hard drive.

It didn’t matter.

For the first time, I wasn’t writing to be heard by them.

I was writing to hear myself.

On quiet mornings, I sit on the cabin porch with a mug of coffee and watch the fog roll over the hills. The mug is the same chipped ceramic one I held the day the first hearing notice came through—the faded American flag almost worn off now from years of dish soap and hot water.

It used to remind me of the day I learned my own family thought of me as a resource to be harvested.

Now it reminds me of something else.

Of the boy who left home at fifteen with a duffel bag and a crumpled letter.

Of the man who sat in a courtroom and refused to be rewritten.

Of the moment a judge asked, “Did you, or did you not?” and the silence that followed.

That silence was my real victory.

Not the $134,000.

Not the arbitration.

Not the article or the comments.

The silence.

The part where there was nothing left for them to say.

The last thing my father ever said to me—through an email Rani forwarded—was, “We didn’t think you’d fight back.”

The last thing I ever said to him was a single sentence typed from the porch of my cabin, the chipped mug warm in my hand:

“That was your first mistake.”

People talk about closure like it’s a door you shut once and never think about again.

Turns out, it’s more like a drafty window. Most days you barely notice it. Some nights it whistles.

For a while after the arbitration, life settled into something that almost felt… normal. My days fell into a rhythm: wake up, make coffee, log into work, standup meeting, product roadmaps, bug triage, mentor calls, end of day. I’d shut my laptop, pull on a hoodie, and step out onto the porch just as the sky started going lavender over the tree line.

I got used to the quiet up there.

In the city, silence feels like something’s wrong—like a notification didn’t come through or an ambulance went the other way. In the mountains, silence feels like a blanket. Crickets. Wind through pine. The occasional car on the distant highway, more suggestion than sound.

For the first time since I was fifteen, nobody needed anything from me.

No calls.

No threats.

No envelopes on the doorstep.

It should’ve been perfect.

In some ways, it was.

In others, it was like learning to walk without a weight you’d carried for so long your muscles didn’t remember how to move without it.

The first therapy session I’d booked months earlier finally came due two weeks after I moved into the cabin. I almost canceled. Old habit—if it costs money and it’s for me, it’s probably not “necessary,” right?

I went anyway.

My therapist, Dr. Patel, had an office in town wedged between a nail salon and a diner with a permanently flickering OPEN sign. The waiting room had the standard issue potted plant and a stack of dog‑eared magazines with last year’s dates.

“This is your first time in therapy?” she asked when I sat down.

“First time paying for it,” I said. “I’ve had the court‑mandated kind of ‘family talks’ before. They don’t count.”

One corner of her mouth twitched. “Fair enough.”

We talked. Or rather, she asked questions and I tried to pretend I wasn’t giving closing statements again.

“You tell your story like you’re on the stand,” she said gently at one point. “Very organized. Very persuasive. Very external. Where’s the part where you tell it just for you?”

It knocked the air out of me more than any cross‑examination had.

Because she was right.

I knew how to argue facts.

I didn’t know how to admit out loud that some nights I still woke up convinced there’d be a sheriff at the door. That sometimes when my phone buzzed with an unknown number, my hands went cold.

Or that even after winning—twice—some part of me still felt like maybe I’d missed something.

Maybe there was a test I hadn’t studied for.

Maybe someone would show up and tell me the verdict didn’t count.

It took months, but the more I went, the more the story in my head started to shift.

Not the facts.

Those stayed the same.

The guilt.

That’s what finally started to move.

“You keep asking if you did the right thing,” Dr. Patel said once, when I was deep in a spiral about the arbitration money. “Let me ask you this: if a stranger showed you the exact same documents your parents forged, would you hesitate to call it fraud?”

“No,” I said immediately.

“Then why does it feel different when it’s them?”

“Because they’re my parents,” I said.

“Are they?” she asked quietly. “Or are they two adults who happened to raise you?”

It wasn’t a question I could answer in one session.

But it sat with me.

Like the letter Ms. Carter wrote. Like the chipped mug with the faded flag.

Little anchors to a new reality.

About six months after the appeal, I drove back to the Bay for the first time—not to see them, but to speak at a career panel at my old community college. My former econ professor had emailed out of the blue.

“Current students could really benefit from hearing how you navigated things,” she wrote.

I almost declined.

Then I thought about the kid I used to be, eating instant noodles on that cracked plastic bench.

I said yes.

Standing at the front of that classroom felt stranger than any courtroom.

The fluorescent lights buzzed. The whiteboard marker squeaked. Twenty‑something students looked at me like I was some kind of success story.

“Be honest,” one of them said during Q&A, a girl with purple braids and a community‑college hoodie. “Did you ever feel like you were just… too far behind to catch up?”

“All the time,” I told her. “I felt like that walking into every class, every interview, every new job. The only difference is now I know feeling behind doesn’t mean you are behind. It just means you’re paying attention.”

She smiled at that.

Afterward, one of the organizers handed me a small envelope.

“Travel stipend,” she said. “It’s not much.”

It was a check for $150.

Twelve years ago, I would’ve stretched that for groceries and bus passes for a month.

Now, I drove straight to the old shelter.

The building hadn’t changed much—a new coat of paint, a different sign—but the smell when I walked in was the same: industrial cleaner and burnt coffee.

George, the guy who’d run the place when I lived there, was retired, but a younger staffer recognized my name from the donation logs.

“You’re the blanket guy,” she said.

I huffed a laugh. “Yeah, I guess that’s me.”

I endorsed the check and slid it across the desk.

“For whoever needs it most,” I said.

Driving back to the cabin that night, I realized something that should’ve been obvious sooner: my family had taken enough from me.

My guilt didn’t owe them anything, either.

The world kept turning.

My job got busier. Promotions came with more responsibility, not just more money. I hired people. Led projects. Screwed things up. Fixed them.

On weekends, I split wood for the stove, learned which neighbors I could call if my truck wouldn’t start, which back roads washed out first during heavy rain.

I built a life.

A small one.

But a real one.

Every now and then, though, the past would tap on the glass.

A mutual friend would text me a screenshot from social media—a vague post from Owen about “toxic people” and “fake family.” A cousin I barely remembered sent a friend request and then a DM: “Heard some wild stuff. You doing okay?”

I didn’t reply.

Because explaining what had happened always turned into defending what I’d done.

And I was tired of being on trial in conversations I hadn’t agreed to have.

About a year after the appeal, an email popped up in my inbox with the subject line: MARSHALL V. MARSHALL – ACCOUNTING COMPLETED.

It was from Rani’s office. The judgment funds had all been disbursed. Every last cent of the $134,000 had cleared.

No more paperwork.

No more hearings.

No more anything.

Underneath the formal update, Rani had added one line:

“If you ever want to expunge your record of them emotionally, I recommend a very expensive dinner on their dime.”

I laughed out loud.

Then I booked a table at a restaurant in the city I’d always walked past but never gone inside.

White tablecloths. Cloth napkins. A menu with no dollar signs, which is how you know you should be scared.

I invited two people: Ms. Carter, and Marcus, my old shelter roommate.

They both tried to argue when they saw the prices.

“Henry, this is ridiculous,” Ms. Carter said, eyes wide behind her glasses. “You don’t have to—”

“I know,” I said. “I want to.”

Marcus shook his head, grinning. “Man, if we told nineteen‑year‑old us we’d be here, he’d think we were having some kind of shared delusion.”

We ordered too much.

A bottle of wine I couldn’t pronounce. Steak. Dessert. Coffee that came with a tiny silver cream pitcher.

When the check came, Ms. Carter reached for her purse.

“Put that away,” I said.

“This isn’t about showing off. It’s… something else.”

“What then?” she asked.

I thought of court documents. Loan statements. Arbitration orders.

“Reallocating resources,” I said finally.

They laughed.

But for me, it was a hinge moment.

A reminder that money taken from me under threat had turned into money I could spend freely on people who’d actually helped me.

That night, after I drove them both home and made the long climb back up to the cabin, I poured myself a glass of tap water, sat on the porch, and lifted my chipped flag mug in a private toast to no one in particular.

To the boy I’d been.

To the man I was.

To every path that branched off the one my parents had planned.

Life didn’t magically become easy after that.

Old wounds don’t care how many court cases you win.

Sometimes, when work got stressful or I skipped therapy for too long, I’d find myself scrolling through old text threads with no names—just numbers and the label “Blocked.”

Sometimes I’d hover over the “Unblock” button.

I never pressed it.

Then, two years after the appeal, the universe decided to test my resolve.

I was in town picking up groceries—eggs, coffee, a new bag of dog food for my neighbor’s mutt I’d adopted partial custody of—when I heard my name.

“Henry?”

I turned.

Owen stood near the automatic doors, a plastic grocery basket hanging off one arm.

For a second, the fluorescent lights and the hiss of the sliding doors disappeared. All I saw was the thirteen‑year‑old version of him, grinning in a brand‑new jersey while I tried not to stare at the holes in my own sneakers.

Then he shifted, and I saw the thirty‑year‑old in front of me.

He looked… smaller somehow.

Not physically. Just less inflated. Less sure of his place in the world.

“Hey,” he said.

It wasn’t much.

It felt like a lot.

“Hey,” I said back.

We stood there in the canned‑goods aisle, separated by a pyramid of discount Gatorade.

“How’ve you been?” he asked.

“Good,” I said. “You?”

He huffed a laugh that didn’t reach his eyes. “You know. Working. Existing.”

I could have walked away.

Some part of me desperately wanted to.

Another part was weirdly curious.

“How’d you know I shop here?” I asked.

He looked embarrassed. “Didn’t. I moved up here a few months ago. Cheaper than the city. Guess we both had the same idea.”

Of course we did.

Our lives had always been tangled, even when I tried to cut the lines.

“Look,” he said, voice dropping. “I’m not gonna do the whole ‘I didn’t know’ thing again. You were right. About everything. I just…”

He trailed off, staring at the floor.

“What do you want, Owen?” I asked.

“Nothing,” he said quickly. “I swear. I just—when I saw you, I figured I should say… something.”

“Okay,” I said slowly. “Say it.”

He swallowed.

“I was a jerk,” he blurted. “Back then. In court. Before court. After. I let Mom and Dad tell me who you were because it was easier than asking. They told me you were selfish. And I liked that version better than the one where maybe they were the problem.”

I stayed quiet.

“I lost a lot,” he said. “After everything came out. Jobs. Friends. People saw that article and decided I was radioactive.”

He laughed again, bitter this time.

“At first I blamed you for that, too,” he admitted. “Figured you’d pulled strings, blacklisted me or whatever. Then I actually read the damn thing again.”

He met my eyes.

“For the first time, I saw how it must’ve looked from your side,” he said. “I don’t expect you to forgive me. I just… needed you to know I’m not hiding behind them anymore.”

I let the words sit between us.

A few years earlier, I might’ve rushed to fill the silence. To make him feel better. To reassure him.

I didn’t do that this time.

“I’m glad you figured that out,” I said finally.

“That’s it?” he asked, a flash of the old Owen surfacing—expectant, a little offended.

“What were you hoping for?” I asked. “A hug? Credits rolled? Family dinner at Applebee’s?”

He winced. “No. I just… I don’t know.”

“You came here for your own reasons,” I said. “You said what you needed to say. That’s about you. My response is about me. And right now, what I can honestly say is I’m glad you’re not lying to yourself anymore.”

He nodded slowly.

We stood there in the hum of grocery‑store air‑conditioning and Muzak, two grown men with a childhood between us like a minefield.

“Do you ever talk to them?” he asked suddenly.

I knew who he meant.

“No,” I said.

He nodded like he’d expected that.

“They’re not doing great,” he said. “Money‑wise. Socially. Uncle Frank won’t let them in the house anymore. Word gets around in small towns.”

I didn’t feel joy.

Didn’t feel vindication.

Just a sort of quiet inevitability.

“You warned them,” he added. “In court. You told them they couldn’t rewrite you.”

“I warned them a lot of things,” I said.

We stood there another moment.

Then he shifted his basket to the other hand.

“Anyway,” he said. “I’ll get out of your way. I’m, uh, living over on Pine Ridge if you ever… if you ever need anything.”

For the first time, I almost laughed.

“I appreciate the offer,” I said.

He took a step, then paused.

“Henry?”

“Yeah?”

“That day in court,” he said quietly. “When you looked at me and said you’d stopped covering for me… that was the first time I realized you weren’t just my big brother. You were your own person.”

He swallowed.

“It scared the hell out of me,” he admitted. “Still does a little.”

Then he walked away.

I watched him go.

My heart didn’t pound.

My hands didn’t shake.

When I got back to the cabin, I set my groceries on the counter, took my chipped mug down from the shelf, and made coffee even though it was late.

I sat on the porch and watched the sky go from blue to black.

Every once in a while, a car passed on the distant road, its headlights cutting a brief white line through the trees.

Dr. Patel would probably have a lot to say about the grocery‑store encounter.

I didn’t text her.

Didn’t need to.

Because for the first time, seeing Owen didn’t drag me backward.

It just confirmed what I already knew.

We’d grown up in the same house.

But we’d never lived in the same story.

People like to say blood is thicker than water.

They forget the rest of the phrase.

The original saying goes, “The blood of the covenant is thicker than the water of the womb.”

The bonds you choose are stronger than the ones you’re told you’re stuck with.

My covenant was with the kid who slept in shelters and still made it to class.

With the guidance counselor who saw me when my own parents didn’t.

With the roommate who remembered my cracked hands and open textbooks.

With the version of myself who stood in front of a judge and said, “I refuse to let the people who left me behind profit from my survival.”

That night on the porch, I made a quiet decision.

I couldn’t change where I came from.

But I could decide where my story went next.

A few months later, Ms. Carter emailed me again.

“You ever thought about doing more formal mentoring?” she asked. “We’ve got a scholarship fund that could use your kind of stubborn.”

Her words, not mine.

I drove down for a meeting and walked out somehow agreeing to serve on a small advisory board for students coming out of unstable homes.

We met once a quarter in a bland conference room with bad coffee and good intentions.

I listened to kids talk about juggling night shifts with homework, about sleeping in cars, about trying to fill out FAFSA forms with parents who’d vanished or might as well have.

I didn’t have answers for everything.

But I knew how to say, “You’re not crazy. This is hard.”

I knew how to say, “You’re allowed to build a life that doesn’t include the people who broke you.”

Sometimes, after those meetings, I’d drive back to the cabin and take the long way, past fields and old barns and a roadside stand that sold peaches in the summer and Christmas trees in December.

I’d park on the shoulder, roll down the window, and just breathe.

Because for a long time, I’d believed my only choices were martyrdom or complete estrangement.

Now I knew there was a third path:

Live.

Build.

Protect what you’ve made.

Help when you can.

Walk away when you must.

The last real communication I got from my parents came almost three years after the appeal.

It was a letter.

Handwritten.

No return address, but the handwriting was my mother’s.

My first instinct was to drop it straight into the trash.

Instead, I put it in the freezer.

Literally.

Dr. Patel had once joked about that as a tactic—“If you’re not ready to read something but not ready to throw it away, put it somewhere ridiculous until you are.”

So there it sat.

Between a bag of frozen peas and a carton of ice cream.

For three months.

I finally opened it on a rainy Sunday when the power flickered and I’d already read every book I owned twice.

The letter was exactly what I expected and nothing like what I needed.

Pages of careful script, more about them than me.

They were “sorry things had gotten so out of hand.”

They “never meant to hurt” me.

They “hoped one day I could understand the pressure they’d been under.”

At the bottom, one line stood out:

“We are your parents, Henry. That has to mean something.”

I stared at that sentence for a long time.

Then I picked up a pen and wrote in the margin:

“It does. It means you had the first chance to do right by me. You chose not to.”

I didn’t mail it.

Didn’t send a copy.

Some words are just for you.

When I was done, I folded the letter back up and slid it into a folder in my desk labeled DOCUMENTS – CLOSED.

Not because I forgave them.

Not because I forgot.

Because the story they were trying to tell about me had finally lost its power.

The last time I saw Owen was about a year after the grocery‑store encounter.

I was driving down the mountain road at dusk when I spotted a familiar truck on the shoulder, hood up, hazard lights blinking.

I pulled over on instinct before I registered the license plate.

He looked up, squinting in the fading light.

“Of all the people,” he said, half laughing.

“Car trouble?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Starter, I think. Or battery. Or something I can’t afford right now.”

There was a time when that sentence would have been aimed at me like a fishing line.

Now, it just sounded like weather.

I popped my trunk, pulled out a set of jumper cables, and handed him one end.

“I’ll give you a jump,” I said. “After that, you’re on your own.”

He nodded.

We hooked up the cables in silence.

When his engine finally caught, he let out a breath.

“Thanks,” he said. “Really.”

“Drive straight to a shop,” I said. “Don’t stop.”

He hesitated.

“You know,” he said, “sometimes I think about what would’ve happened if you hadn’t left. If you’d stayed and kept… absorbing things for everyone.”

“I’d probably be in the passenger seat of that truck, wondering why it never goes anywhere,” I said.

He smiled, sad and sharp.

“Yeah,” he said. “Probably.”

He climbed into his truck, gave me a short wave, and pulled back onto the road.

I watched his taillights disappear around the bend.

Then I turned my own car toward home.

The cabin lights glowed warm when I pulled into the drive.

Inside, I set my keys in the same bowl by the door, filled the chipped mug with water, and watched steam curl up in the kitchen light.

My life wasn’t perfect.

But it was mine.

And that, after everything, was the whole point.

Sometimes, on clear nights, I sit on the porch and tilt the mug so the last sliver of the faded flag catches the moonlight.

I think about courtrooms and shelters, about forged signatures and real ones. About the difference between family you’re assigned and family you assemble.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s this:

You don’t owe anyone access to the life you bled for just because you share a last name.

Respect is earned.

Trust is built.

Love is proven.

And freedom?

Freedom is standing on your own porch, in a house with your name alone on the deed, lifting a chipped mug toward the dark and knowing that whatever comes next, you’ll face it as the person you chose to become—not the role someone else tried to write for you.

My father once told me, “We didn’t think you’d fight back.”

He was wrong.

I didn’t just fight.

I won.

And I walked away.

That was their last mistake.

And my first real beginning.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load