I flew back to Ohio from Denver the Tuesday before Thanksgiving under a lid of Midwestern gray. Half-melted snow ringed the runway, the kind that sticks to grass like a bad haircut. The wind cut through my jacket no matter what the tag had promised. I was twenty, tired from classes and two part-time jobs, telling myself that a few days at home would put my head back on straight.

Grandpa Harold waited at arrivals with a scrap of cardboard that read in his square handwriting: NATHAN — UNPAID FARMHAND. I smiled before I even reached him. That was Grandpa: quiet until he spoke, and then whatever he said landed. He hugged like he meant it and steered me toward his old truck without a speech. On the drive he pointed at a deer on the shoulder and grumbled, “People used to know how to drive in snow.” He flicked the wipers once, as if the truck needed to hear that too.

Our neighborhood looked like it was holding its breath. The house should have been warm—porch light on, pie cooling somewhere, a game droning from the living room. Instead, dark windows, no wreath, no sound. Inside, the carpet looked untouched, the kitchen too clean. The fridge hummed in a way that felt like someone clearing their throat in an empty church. It felt like the place had been staged for strangers.

I checked my phone. A text from Dad, three hours old: We spent your $7,000 on a family vacation. Have fun. Attached was a photo—Mom, Dad, my sister Madison, and the dog in matching Hawaiian shirts under a resort sign. The caption: Maui 2025.

I stared until the phone got heavy. They’d gone without telling me—gone on Thanksgiving week—and used the cash I’d saved all summer. I’d earned it bagging groceries at Kroger and power-washing decks until the boards flashed like new skin. I kept the cash in a shoe box because last year an auto-draft had eaten my rent in one bite and left me apologizing to my landlord. I showed Grandpa. He studied the screen a long time, face blank, then said in that calm, Ohio River voice, “We’ll show ’em where the crabs hibernate.”

I hadn’t heard that line since I was a kid. It meant: I’m not going to shout. I’m going to end this properly.

He woke me before dawn, slid a chipped mug of coffee in front of me, and set a yellow legal pad on the table. “Write it all,” he said. “Where you earned it, where you kept it, every dollar.” I went upstairs to grab the shoe box—$8,170 in twenties and fifties—and found an empty space on the closet shelf. Dust undisturbed. The absence as clean as a lie.

It stopped being a family slight. It became theft.

I brought the list downstairs. Grandpa read without comment, then reached for the landline because he liked the weight of consequences in his hand. He called Benny, who fixed things that didn’t want to be fixed. He called a lawyer he knew from a VFW poker night—Mr. Kramer, a man who could fold paper into a weapon. He called his old friend Ed, who used to work at the sheriff’s department and still believed paperwork had a spine.

By dinner he had a plan: legal pressure, public shame, and a few polite, certified warning shots aimed at the three places Dad valued most—his job, his accountant, and his country club. Grandpa wasn’t angry. He was exact. You don’t get to eighty-two by wasting breath.

Thanksgiving morning I woke to the clack of his WWII-era Remington. He’d dragged it from the attic and set it in a square of sun like a machine that feeds on daylight. On the table: folders of receipts, mortgage statements, my tuition bill, and in the middle, my list. He typed like a carpenter, each line measured and true.

When he finished, he slid me a letter addressed to my father. It named the amount, the dates, and the fact that the cash had been kept in my room and had disappeared the night before their flight. It cited Ohio’s theft statute. It set a deadline for return and noted that a report had been initiated. No insults. No adjectives. Just the truth fenced in so it couldn’t wander.

He made three certified copies and mailed them to Dad’s employer, to Dad’s accountant—who also handled Uncle Rick’s taxes—and to the membership committee at Brookline Hills Country Club. “Polite artillery,” he said, licking the envelopes like stamps were vows. “The kind that lands on time.”

Wave two began at First Federal. We sat down with Carla, the senior teller with earrings like little steering wheels and a habit of looking you straight in the face. She slid forms across the desk.

“Student account?” she asked.

“Joint,” Grandpa said, tapping the line with a square fingertip. “Primary Harold Whitaker, co-signer Nathan Lawson.”

Carla’s eyes softened at my name. “You family?” she asked Grandpa.

“I am the part that keeps records,” he said.

She nodded as if that were a job title. We opened the account. Grandpa deposited a ceremonial hundred and called it bait. “Not for fish,” he told me in the parking lot. “For finding out which cat will stick his paw where it shouldn’t.”

From there we went to Kenny’s garage print shop. The place smelled like ink and gasoline, and the press thumped like a heart that had decided never to stop. Kenny printed save-the-date postcards for Grandpa’s fictitious 75th birthday party, set for Sunday at five at our address. In cheerful fonts: “Drop in to celebrate Harold—coffee is on!” In smaller type: “Bring your favorite story about Harold (and any old receipts you’ve been meaning to show him).” The guest list: Mom’s Pilates friends, her church group, and neighbors whose opinions traveled faster than the mail.

Ed called with good news wrapped in bad: the doorbell camera had my father, midnight Tuesday, entering from the garage, going straight upstairs, and leaving with the shoe box eight minutes later. A bank kiosk by the airport recorded him swapping cash for travel cards two hours after that. The travel agency printed an itinerary to Maui for two adults, one child, and a pet-friendly reservation. Times and amounts matched.

“Technology doesn’t care about your story,” Ed said. “It cares about timestamps.”

Thanksgiving at our place is usually loud by nine. That morning the furnace did all the talking. Grandpa and I ate eggs, then loaded turkeys at the community center for the church drive. He believed holidays had two modes: serve, or stand your ground. Sometimes both. A boy in a Bengals hat tried to carry a bird bigger than his torso and laughed when Grandpa called him “powerful.” A woman cried when we gave her an extra pie. Grandpa pretended not to notice and asked if she liked pecan or apple better. “Depends,” she said, “on whether you steal the pecans from your mama’s pantry or buy ’em.” We all laughed more than the line deserved.

On Black Friday, the certified letters landed where they needed to. The postcards went in the mail. We filed a small-claims case for $8,170 plus fees and interest, and an affidavit asking the court to restrain Dad from moving assets that might concern the case. The clerk praised Grandpa’s tidy forms. “You can ask a court for courtesy,” he told me in the truck. “Sometimes they give it.”

Saturday morning, phones started pinging like hail on metal. Mom: Call me now. Then: That money was family money. Then: Your grandfather will get your father fired. Grandpa flicked my phone to silent. “They don’t get you on the hour,” he said.

An unknown Maui number texted a picture from the resort pool: my parents smiling like effort, Madison gripping the dog like a prop. No caption. It didn’t need one. Erin from Pilates called my mother to ask what to bring to Sunday’s party. The church ladies coordinated casseroles with military efficiency. Dawn at the accountant’s office left a message for my father using words like “urgent,” “documentation,” and “reputational risk.” HR from my father’s company emailed him a meeting invite for Monday at 9 a.m. with “Integrity Review” in the subject line. Grandpa skimmed, nodded once, and poured more coffee.

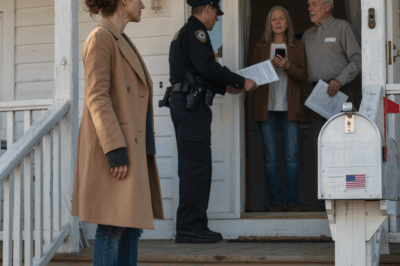

By noon, a detective Ed trusted called to say he’d stop by. He brought the doorbell footage on a thumb drive and ATM stills from a grocery near the airport. “County’ll decide how to handle it,” he said at our table, flipping through pages. “But facts are facts. Do you want to press charges?”

I looked at Grandpa. He didn’t move.

“Yes,” I said. “But I’ll drop them when the full amount is returned, with a signed admission of debt and an agreement to counseling for financial abuse. And my father stops using my name as a prop at the club.”

The detective nodded. “I like a conditional. Gives a man a door and a wall at the same time.”

A storm over the Pacific delayed their flight home to Sunday afternoon. In the meantime, Grandpa turned our dining room into a courtroom that smelled like coffee. He set the good plates, lined the mantel with “scrapbook” contributions from neighbors—printouts of Venmo requests labeled “emergency,” texts asking for short-term floats, a receipt from a neighbor who’d paid Dad $500 cash for lawn care I remembered doing. He stacked the documents by type and date the way a mason stacks bricks. “A wall,” he said, patting the top sheet. “So the wind can’t talk you out of what you know.”

Kenny delivered a little pamphlet that looked like a church bulletin: Grandpa and me holding a turkey at the community center on the cover; inside, the line in fine print—“If you’ve ever ‘lent’ cash to Charles Lawson for a ‘family emergency,’ bring receipts. We’re making a scrapbook.” I raised an eyebrow. “You asked people to bring receipts?”

“I asked them to bring truth,” he said.

By four on Sunday, our driveway looked like Thanksgiving again. Minivans. Trucks. Church ladies with Pyrex that steamed up the cold air. Erin from Pilates with a glittering salad. Ed in a sport coat. Dawn from the accountant’s with the look of someone who had said “ethics” out loud at work. People hugged Grandpa, shook my hand, and tried to act like they didn’t know why they were really there.

At four-thirty a rental SUV slid in crooked. My parents climbed out wearing airport faces; Madison hovered, chastened; the dog barked at the door sign: WELCOME, FRIENDS. COFFEE IS ON. RECEIPTS TO THE MANTEL. A neighbor, Mr. Larkin, pretended to adjust his hat and didn’t move.

Grandpa met them on the porch. “Harold—” Dad began, trying to shoulder past.

“Charles,” Grandpa said, the bull-stopping voice. “You’ll be polite in my house.”

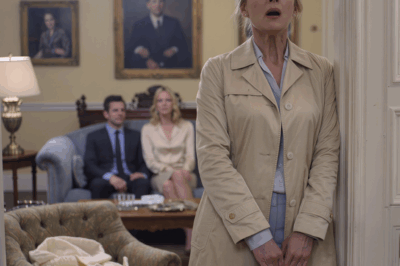

Mom’s smile was a piece of Tupperware—snapped on and empty. “What is all this?” she asked.

“Receipts,” Grandpa said. “The kind you prefer not to keep.”

“You weren’t even going to be here,” Madison blurted at me, then stopped when she saw my face. “I—he said—” She swallowed the rest.

I stepped forward. My voice didn’t shake. “You took $8,170 from my room,” I said to my father. “The doorbell camera shows you. The bank kiosk shows you converting it to travel cards. You texted me that you spent my money on a vacation. You did it on Thanksgiving week.”

“That money was family money,” Mom said. “He paid for your roof.”

“I paid rent when you asked,” I said. “Shelter isn’t a tip jar.”

Dad tried a different angle. “You hid cash in a shoebox,” he said, as if that were a crime.

“I hid cash because last year a bank fee ate a week of groceries,” I said. “I hid cash because I learned it from you.”

Ed held up a small folder. “Report’s on file,” he said. “County reviews tomorrow. If you’d like to keep HR out of a deposition, sit down and cooperate.”

Inside, Grandpa poured coffee like it sealed agreements. He set a legal pad before my father. “Write, ‘I, Charles Lawson, will return $8,170 to my son, Nathan Lawson, by Monday 5 p.m.,’” he said. “Sign it.”

“This is humiliation,” Dad said.

“This is arithmetic,” Grandpa said.

My father looked at the mantel crowded with small, unglamorous truths. He took the pen. He wrote, slow. He signed. He dated.

Dawn cleared her throat. “There’s also restitution,” she said gently. “Borrowing under false pretenses has tax implications.”

“Dawn,” Mom hissed.

“Linda,” Dawn said back, polite as porcelain and hard as it.

Grandpa laid out one more paper. “And you will write that you will not access my accounts, devices, or mail without my written consent,” he told my father. “Sign it.”

He signed.

The room changed temperature. People didn’t applaud; they exhaled. Ed photographed the documents and took a check Dad wrote on the spot for two thousand as a down payment. “Zelle the rest by five tomorrow,” Ed said. “Don’t make me come get it.”

Mom asked to talk privately. “We’re talking where the receipts are,” Grandpa said. “Apologize where you stole.”

“I’m sorry,” she said—to me, to the room, to the truth finally let out of its cage. “We told ourselves it was family money. We were wrong.”

She sat. Madison’s hands twisted in her sleeves. When everyone drifted toward the kitchen—because casseroles ignore lawsuits—she stayed by the table with me.

“I was scared,” she whispered. “He told me you weren’t coming home. He said you didn’t care about us.”

“I care,” I said. “I also care about not being stolen from.”

She nodded, a tiny motion with a lot of learning behind it. “I’ll make it right with you too,” she said. “However you say.”

“Start with telling the truth when it’s small,” I said. “And don’t let anyone spend your name without your permission.”

On the porch later, with the cold leaning in and the neighborhood calm, Grandpa handed me a fresh mug. A snowflake landed in it, melted, and disappeared like a thought I would have had if this week had gone differently. “You kept your feet,” he said.

“I had your table,” I said.

He nodded. “Witnesses help.”

Zelle pinged three times Monday: $6,170 in the morning, $1,000 at lunch, $1,000 at dusk with a note that read, simply, I’m sorry. I forwarded the screenshots to the detective and Dawn. HR placed Dad on leave pending review. The club suspended his membership “until matters are resolved.” The accountant declined to file his taxes “due to a conflict of professionalism.”

That night Grandpa pulled the typewriter back into the center of the table. “One more letter,” he said. He wrote to me. It said I was not unpaid. It said I had spent years paying with silence and small exits and that this week I’d balanced the ledger. It said a table feeds; it does not pin. It said love without accountability is sugar water—sweet, useless, sticky. It said he was proud—not because I won, but because I refused to cheat.

He signed it with his blocky name and slid it across to me. I put it in a clear sleeve with the signed page from my father. Truth loves to look ordinary.

The week stretched into December. Snow came down in sheets that erased the neighborhood’s hard edges. HR sent a letter placing Dad on administrative leave. The club made a show of “investigating,” which meant they would wait to see if someone they golfed with got mad. Madison texted a long apology that began with, I was scared to disagree, and ended with, I want to be better. I told her better is a daily choice, not a post.

Grandpa and I put up the same brittle box of lights we always used. He told me about the winter the river froze solid and how his father had taught him you test the ice with a pole before you trust it with your weight. “Same with people,” he said. “Same with institutions. Tap, listen, then step.” We ate chili thick enough to stand a spoon in and watched a movie so old the credits looked like they’d been carved.

On a Monday before Christmas, HR emailed again: leave lifted, final written warning in Dad’s file, counseling to continue, restitution acknowledged. The club reinstated him under probation. The accountant sent a card with a photo of his corgi and, in neat script, “Best of luck next semester.” Dawn texted a calculator gif that somehow looked like a victory parade. Ed brought fudge and told me I’d used my voice like a tool instead of a weapon.

Madison came by with the dog in a sweater that made him look like a senator. She stood in the kitchen where all of this had started, looked at the mantel where the scrapbook of receipts now sat bound in a three-ring binder, and said, “It’s ugly, but it’s honest.”

“It’s a map,” I said. “Ugly ones still get you there.”

On a clean blue Sunday in March I drove out to Grandpa’s. The porch smelled like thawing earth. We sat with coffee and didn’t say much. We didn’t need to. The table inside had done its work. A robin hopped in the yard like it had survived something it didn’t want to talk about.

“I keep thinking about walking into that empty house,” I said. “How loud the quiet was. How certain it felt, all at once, that no one was coming.”

He nodded. “Sometimes the lesson is that the people you’re waiting for aren’t the ones who will show,” he said. “Sometimes it’s you. Sometimes it’s me. Sometimes it’s the woman at the food drive who knows the difference between stealing pecans and buying them. Family is who brings receipts and stays for coffee.”

I don’t start my story with the country club or HR or certified mail when people ask what happened. I start with tables. Your first table is the one you’re given, and sometimes the people who set it forget the difference between a seat and a leash. When they do, you build a new table. You put it where the light is good. You invite the ones who carry truth like paper and show up with casseroles. You leave an open chair for the ones still learning the difference between applause and a paycheck. You pour coffee even for the people you’re mad at, because coffee isn’t forgiveness, but it’s an open door.

This is the part I don’t put on postcards: Five days after I walked into an empty house, my parents stood on a porch, crying and begging me to fix a problem they had made for themselves. I didn’t fix it for them. I fixed my part. I paid myself back with boundaries and paper. I watched my grandfather turn a typewriter into a lighthouse.

He still signs his notes the same way: Keep your feet. Keep your face. Keep your receipts. And in small print at the bottom, like a joke told after the audience has gone home, he adds: The crabs are sleeping fine.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load