The afternoon my husband handed me divorce papers, he did it with the practiced indifference of a man returning a defective appliance. The envelope slid across our granite island and bumped my coffee mug—my grandmother’s mug, hairline crack down the handle like a vein of quartz—before coming to a stop against my palm.

“Harper, I need you to sign these.”

He said it without eye contact, the way Brad always said things he didn’t want to own, as if the words were coupons he’d clipped from a circular and set down for someone else to redeem. October sun glazed the Westchester maples outside the breakfast nook. Inside, our kitchen smelled like citrus cleaner and the rosemary chicken I’d meant to roast tonight before his ultimatum rearranged the furniture in my head.

“You have forty‑eight hours to get your stuff out,” he added, that lazy authority he wore like a weekend sweater. “Madison’s moving in this weekend and she needs space for her meditation corner.”

Ah, yes. The meditation corner. As if you could feng‑shui a lie.

I opened the envelope with the kind of calm that makes triage nurses set down clipboards to look twice. I’m a real estate attorney. Paperwork is my native terrain. Contracts talk when you learn their language. They confess in boilerplate.

“Forty‑eight hours,” I repeated, turning a page, then another. “Generous. Considering you’ve been planning this since July.”

Brad’s left eye twitched. That eye could have had its own calendar. It ticked in budget season. It stuttered at traffic. It waltzed during arguments and it absolutely samba’d when he was caught.

“You knew?” He tried for surprise and landed squarely on unprepared.

“Honey, you started ‘going to yoga’ five times a week and discovered green smoothies at forty‑three. You’re about as subtle as a marching band in a library.” I flipped to the signature page and let my gaze drift the way a diver tests current. “Sedona isn’t famous for financial advisory conferences, is it?”

He searched my face for softness and found the stainless steel of my grandmother’s cutlery instead. My grandmother, Rose Caldwell, taught me two things that matter: how to pull a deed faster than a magician pulls a scarf, and how to stay quiet while a man tells on himself.

“Don’t make this difficult,” Brad said, adopting the tone he’d honed in couples therapy—an olive branch dipped in condescension. “Madison and I have found something real. She understands my spiritual journey.”

Brad’s spiritual journey had thus far consisted of thinking about golf during traffic lights and forgetting to separate darks from lights. I set down the packet and looked at the man I’d spent eight years loving, managing, editing, forgiving. I looked and felt that precise, fine anger that arrives when injustice walks in and takes a chair it didn’t pay for.

“Is that what we’re calling it,” I asked, “when a middle‑aged financial advisor is seduced by a woman who still gets carded at Applebee’s?”

He flinched. “Bitter isn’t attractive, Harper.”

“Oh, sweetheart,” I said, and smiled the way sharks smile. “I haven’t even warmed up.”

If Brad had truly known me—beyond my grocery lists and my court shoes—he’d have remembered I wasn’t built for begging. I was built for evidence. The week he first came home scented like sandalwood and platitudes about opening heart chakras, I’d taken out my laptop and what Rose used to call the good scissors.

“Knowledge is power,” Grandma would murmur, sliding county records across the dining table to twelve‑year‑old me, the way other grandmothers slid cookies. “But timing is everything.”

I learned to follow money because it was my job. I learned to follow people because it was her art. By the time Brad cleared his throat and asked whether we could be “amicable” (pronounced: painless for him), my file was thicker than his denial.

Madison Rivers was not Madison Rivers. She was Melissa Rodriguez two addresses back, and if you lifted the corner of her curated life like wallpaper, you found an older pattern. Four glowing testimonials on a website for “private restorative sessions”: David Peterson, cardiologist from Scarsdale; Michael Harrison, car dealerships in Stamford and Norwalk; James Mitchell, Greenwich hedge fund; and my husband, Brad Caldwell, spiritual pilgrim with a corporate card.

I didn’t stumble. I mapped. Monday‑Wednesday: David, whose wife believed cardiac rehab required scented candles and ninety‑minute ‘breathwork.’ Tuesday‑Thursday: Michael, allegedly in grief counseling. Friday: James, decompressing from the markets at a “sacred energy site” conveniently adjacent to an overpriced spa. Weekends: Brad, conquered by a woman whose Instagram fed the world inspirational quotes cropped against sunsets and leggings the price of a mortgage payment.

Each man funded a limb of the beast. David paid the Manhattan studio. Michael took on the lease for a white BMW. James underwrote the retreats. Brad covered the “meditation sanctuary” sublet with the floor pillows and the fake fiddle‑leaf fig.

These boys were a rotation, color‑coded in her calendar—yes, I found it—by which manipulation worked best: Rescuer. Provider. Savior. Hero. It would have been elegant if it weren’t so stupid. What broke the symmetry was greed. Melissa’s endgame required a house she couldn’t afford and a man she didn’t love to hand it to her. Mine.

Only the house was never Brad’s to give.

Six years ago, I used my inheritance from Rose to purchase this colonial through Caldwell Property Holdings, LLC. My signature sits alone on deed and mortgage, the ink dry as law. Brad loved the kitchen and the tax rate. I loved the firewall.

When he said “forty‑eight hours,” I saw my grandmother in the pantry doorway, smiling around her tea. I saw the narrow ledger where she’d recorded every case she’d chased before retirement: a fountain‑pen atlas of people who underestimated consequences.

“All right,” I said, and gathered the papers. “If Madison needs her meditation corner, who am I to delay enlightenment?”

His shoulders dropped in wary relief. He would tell himself later that I was reasonable, that I’d finally seen the light he claimed to be following. Men like Brad mistake silence for surrender. It’s the last mistake they make comfortably.

I went upstairs, shut our bedroom door, and opened a secure email draft. The subject line wrote itself. The recipients—Patricia Peterson, Victoria Harrison, and Jennifer Mitchell—took thirty seconds to locate. Women keep the Internet’s receipts.

Dear Mrs. Peterson, Mrs. Harrison, Mrs. Mitchell, and future ex‑Mrs. Caldwell, I typed, fingers light and exact. I believe we have something in common. I’ve attached documents you may find relevant to your family finances.

I timestamped everything because juries like clocks and prosecutors love a schedule. Screenshots of simultaneous texts. Bank deposits hopping like stones across ponds into accounts under both names. A color‑coded calendar. Lease agreements. The white BMW. The Manhattan studio. The Sedona “retreat.” Enough to make the IRS perk up and ask who brought pie.

I pressed send at 6:47 p.m. on Friday, October 13, because I believe poetry belongs in the margins of prosecution.

The hornet’s nest buzzed almost immediately. Patricia—voice of a woman who’s said “Your heart will keep beating” to strangers and meant it—called first. “Are you certain?” she asked.

“I don’t make allegations,” I said. “I present evidence.”

Victoria came second, consonants sharp enough to dice onions. Jennifer third, cool as a portfolio review. In fifteen minutes I was moderating a three‑way call that felt less like a conversation and more like ignition. These were not women who trembled. They were women who reallocated resources.

“Coordinated response?” I asked, and the electricity in their yesses could have powered Metro‑North.

We built our little task force like an elegant house: Patricia handled law, Victoria information, Jennifer money. I coordinated. We called it Rose’s Rule without explaining why. At 9:30, Patricia texted: Fraud divisions notified. At 9:35, Jennifer: Cash withdrawals begun. She’s running. At 9:40, Victoria: Social profiles deleted. Cleanup phase.

At 9:45, a white BMW slid into our driveway like a lie finding parking. Melissa—Madison in athleisure—stepped out with takeout bags and a smile designed by a committee. She moved through my front door on a key Brad had given her three weeks earlier, the key I’d already deactivated.

“Brad!” she sang. “I brought Buddha bowls. Let’s celebrate your freedom.”

I closed my laptop, straightened my blazer, and texted the team: Showtime. I want a record.

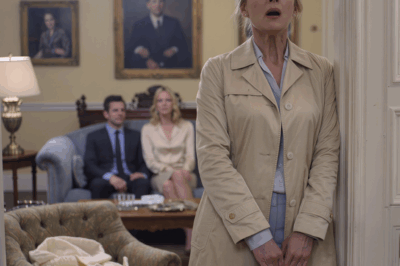

Descending the stairs, I felt that courtroom click—when opening arguments end and the case begins steering itself. In the kitchen, candles burned. My candles. Their warmth painted Brad’s relief and Melissa’s triumph the color of self‑deception.

“Well,” I said, and the room turned to me like a dog to the front door. “If it isn’t Madison Rivers. Or should I say… Melissa Rodriguez?”

Brad’s jaw lost its hinge. Melissa’s face cycled through shades—from influencer pink to misdemeanor green. I set my phone on the island and hit speaker as Patricia called.

“Harper, we’ve filed with the Fraud Division, the IRS, and the AG’s office,” Patricia’s cool voice announced to the kitchen. “We thought Ms. Rodriguez might appreciate the update.”

Melissa reached for her purse and found that panic is heavier than leather. Brad looked from me to her, to me again, a spectator at a match he hadn’t realized he’d entered.

“What is this?” he asked, voice cracking along old adolescent fault lines.

“Four men,” Jennifer said through my phone, calm as water over stone. “Four revenue streams. Four separate stories. Monday through Friday like a shift calendar. She diversified, Brad. Pity you didn’t.”

“Brad,” Victoria added, sugar in the acid, “on Tuesdays and Thursdays she told my husband she was healing him.”

He turned to Melissa, his spiritual journey suddenly a short walk around the block ending at a brick wall. “Tell me this isn’t true.”

“Brad,” she began, reaching for that breathy mysticism, and came up with thin air. “We have something special.”

“You had something profitable,” I said. “And about the house—you can stop drafting your meditation corner. Brad doesn’t own it.”

Now she looked at me. Really looked. “What?”

“Caldwell Property Holdings, LLC,” I said. “Deed. Mortgage. Taxes. All in my name, bought with my inheritance. Brad lives here. I own here. If you step over that threshold again, it’ll be trespassing.”

The grandfather clock ticked in the hall. The refrigerator hummed. Somewhere down the block, a dog barked, uninterested in human tragedy. Melissa’s courage slipped out the back like steam.

Patricia’s voice returned, precise as a scalpel. “Ms. Rodriguez, we have compiled a record of income not reported, identities misused, and funds obtained through deception. You will be dealing with investigators.”

Melissa tried one last script: a sick mother here, a trauma there, a trembling apology like stage glitter. It stuck to nothing. She left the way people do when a mask runs too hot to hold.

The BMW—Michael’s lease—screeched away. The Buddha bowls went tepid on my island. Brad put his hands on the granite and stared at nothing, which turned out to be a mirror.

“Eight years,” he said finally, hollow as a campaign promise.

“Eight years,” I agreed, and blew out the candles. “Rose always said timing is everything—in real estate and revenge.”

Westchester changes in October. The air becomes particular. The trees burn without smoke. On Saturday morning I opened every window in the house and let the cinnamon of fallen leaves push out the residue of sandalwood. I stripped the bed and the guest sheets and anything that had even once been in proximity to Madison’s voice.

I didn’t cry. Crying had come and gone already in a hundred smaller ways over three slower months: finding the second toothbrush in his car’s glove compartment; the way he started locking his phone; the moments his voice went soft over texts that weren’t mine. This was the morning after a hurricane when you stand in the bruised light and think, all right, let’s see what survived.

At 10:15 a.m., my phone chimed. The group chat—Patricia / Victoria / Jennifer—had been renamed ROSE’S RULES by somebody with a grin. Updates stacked. Investigators had questions. Screenshots had homes. A reporter had reached out and been gracefully denied. We weren’t after spectacle. We were after balance.

Brad, meanwhile, discovered that the Venn diagram of “cheated with a yoga instructor who conned three other men” and “retains clients in a town that loves whispers” had a modest overlap. He packed in silence and left with dignity in the trunk. No scene. No drama. Just the slow, mortifying math of consequence.

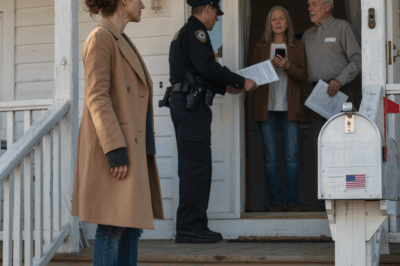

By Monday, the studio Madison rented was shuttered. By Wednesday, a polite woman with a badge asked me to review my documents and sign my name in a neat rectangle. I did. When the state asks whether you are sure, you say yes like you mean it.

On Thursday, I sat with coffee at the kitchen table and read Rose’s recipe for meatloaf and her notes in the margins—“more onion if cold out,” “double glaze if company”—and thought about the woman who used to take me by the hand into the County Clerk’s office and let me smell the dust of other people’s decisions. “You don’t have to be cruel to be thorough,” she’d say. “You only have to know where the light switch is.”

It is a strange thing to gain a quiet. The television did not argue. The dishwasher sighed without witness. The bed took one body and didn’t complain. I worked. I jogged near the reservoir where the geese shouted opinions. I went to court and made bad contractors correct themselves, and at night I learned which lamps made the living room feel like a room and which made it feel like a waiting area.

Two weeks later, Patricia suggested wine. We met at a place in White Plains with brick walls and a bartender who remembered names like a priest remembers sins. Victoria ordered a cabernet that could anchor an argument. Jennifer brought a folder because women like us bring folders even to joy.

“To Rose,” Patricia said, raising her glass. I clinked. The wine tasted like relief that had had time to age.

We told the kinds of stories women tell when they are done apologizing for telling them. Patricia had once convinced a jury to love a defendant by teaching them the names of his children. Victoria had built a campaign that rescues small businesses from Yelp the way lifeguards rescue swimmers who don’t know they’re drowning. Jennifer had stared at a spreadsheet until it gave up and confessed. I told them about the time I kept a woman in her home by finding a two‑year‑old lien nobody else had the patience to look for.

“We should do something with this,” Victoria said. “This energy. This… competence.”

“Clinic?” Patricia suggested. “Pro bono property basics for women.”

“Start with titles,” I said. “And trusts. And how to read a mortgage like it’s trying to lie to you.”

We made lists on napkins and then took photos of the napkins because none of us trust napkins not to betray us.

Brad texted that night. Not a confession; a request. Coffee. Closure. The word some men say when what they want is absolution.

We met on neutral ground, a café that sells biscotti the size of case law. Brad looked smaller, which is not the same as looking thinner. “I’m sorry,” he began, eyes red with the effort of meaning it. “I… I genuinely thought I was in love.”

“I believe you,” I said. “You were in love with how she made you feel about yourself.”

He winced. “I didn’t realize… I didn’t know I could be so stupid.”

“Most people don’t,” I said, and sipped. “That’s how stupid works.”

He asked if there was a path back to friendship. I said there was a path back to decency and he could take it at his own pace. I wished him luck. He cried in the safe, silent way men cry when the world has returned them to their correct size. I put my hand on his for three seconds and then took it back. We both knew where the boundary line ran and what it cost to cross it.

The divorce wound through the system like a slow river. Our lawyers wrote paragraphs. A judge frowned over papers that made more sense than most. We signed where we had to sign. My house remained my house. My future, unshared, looked less like a loss and more like square footage.

Meanwhile, Melissa’s life turned into a docket. Investigations braided, and the braid became a rope. I did not attend her arraignment. I don’t watch people drown. I just make sure they’re not standing on my dock when they start.

It is a gorgeous thing, building something after a fire. You get to decide which beams to keep. You get to be honest about which walls were bearing and which were simply decorative and heavy. Winter came to Westchester with its clean breath. I painted the guest room a white that wasn’t pure because nothing should be. I replaced the fake fiddle‑leaf with a real fern with mistaken confidence and then learned how to keep it alive.

On Sundays, I ran the old roads Rose drove, past the deli where she bought egg salad and the library where she hid in nonfiction. At the clerk’s office, I still feel like a kid sometimes—my calf muscles remember a bench my legs didn’t reach past. The woman at Records knows to bring me the thick pens because I press hard when something matters.

We started the clinic in March. Twenty folding chairs in a church basement. Fluorescent lighting that made everyone look like paperwork. We filled the seats anyway. We called it Keys & Deeds because we were cute when we could afford to be, and because the women who came needed to learn the shape of a key that actually fits a door.

“This is a deed,” I’d say, holding one up. “It tells you who owns. Not who lives. Not who pays. Who owns.” We taught them LLCs and life estates, what a lien looks like in the wild, and how to store documents where a hurricane can’t find them. We taught them to ask questions out loud in rooms where men liked hearing themselves better than the answers.

Some nights I went home and cried the kind of cry that has nothing to do with sadness and everything to do with gratitude finding a pressure valve. Then I made pasta and watched something idiotically cheerful and slept like a person who can tell the difference between loneliness and solitude.

Brad moved to a studio in White Plains with a view of a billboard that sells promises the way summer sells lemonade. He stopped doing yoga. He took up golf. He apologized to his mother, whose opinion he’d always borrowed like an ill‑fitting jacket. He began rebuilding a client list one handshake at a time. I did not hate him. I learned that the opposite of love is not anger. It is space.

One late spring afternoon, I found a letter from Rose tucked behind a recipe for banana bread. My name in her slanted blue. The paper had the faint oatmeal smell of old stationary. I carried it to the porch because some words want outside air.

Harper girl, it began. If you’re reading this, then something has ended or begun—same thing, different lighting. Here is what I know: You are a steward of rooms. You make them safe for people who forget that safety is a thing they’re allowed to ask for. Don’t waste your good eyesight on men who love how they look in your light. And when someone asks you to hurry, ask yourself who benefits from your rush.

I read it twice, then once out loud to nobody. The maple made the kind of sound trees make when they are as satisfied as trees get. I folded the letter back behind the recipe where it belonged, because not every treasure needs a frame.

A year passed. Not like a train. Like a tide.

The house learned me and I learned it. I found which stair creaks at six in the morning and which creaks at midnight and discovered that both creaks are faithful if you feed them oil. I learned the sweet spot where you can stand in the kitchen and smell both coffee and the lilacs when the window is open just wide enough. I practiced being unobserved. There is an art to it—how you move when no eyes edit you.

One Saturday, returning from the farmer’s market with tomatoes that could start wars, I saw Patricia seated with a woman in our church basement, her hands folded in the quiet patience that says I will wait as long as you need to find your courage. Victoria was on the phone in the hallway, her voice a scalpel. Jennifer stood by the coffee urn, reading a ledger, the corners of her mouth turned in a half‑smile that means she’s found the line that will save somebody money.

We didn’t plan it, but we had become what women become when they refuse to choose between competence and compassion. We had become a structure. It stood because we took turns being a beam.

On the way home, my phone buzzed. Brad. A photo of his new apartment: a bookshelf with more books than trophies, a plant that looked determined. A short message: I’m trying. I wrote back: Good. He liked the message. It isn’t fireworks, but then, fireworks are loud and gone. We were building things the way stone walls are built in New England, one patience on top of another.

I stopped, on the walk, at Rose’s grave. It is small on purpose. She liked understatement in everything except truth. “We did it,” I told the grass. “We turned damage into doctrine.” The wind answered in leaves and I took that as blessing because I am allowed to.

If you are waiting for the part where a new man arrives with a dog and a toolbox, I am not saying it cannot happen. I am saying it didn’t have to for this to be a happy ending. I already owned the house I live in and the person who lives in it.

On the anniversary of the envelope sliding across the granite, I made meatloaf the Rose way: more onion because it was cold, double glaze because I was having company—Patricia and Victoria and Jennifer, a bottle of the cabernet that anchors arguments and then forgives them. We ate at my table. The cracks in the mug handle looked like veins of quartz. We toasted quiet victories. We made fun of the patriarchy because mockery is a crowbar and sometimes the only tool you need is leverage.

“Do you ever think about her?” Victoria asked, and we didn’t say the name. We didn’t need to.

“I think about how much work it takes to make a life out of lies,” I said. “And how fast it collapses when truth shows up for inspection.”

Patricia lifted her glass. “To inspections.”

“To inspections,” we chorused, and laughed.

Later, alone in the clearing‑up, I stood at the sink and watched the dark gather over the yard. The maple leaves were the color of old brass. The porch light made a small, sufficient circle. A train sounded faintly somewhere toward the river, doing what trains do—carrying stories into and out of town with no judgment at all.

Grandma Rose used to say karma has excellent credit. It never forgets to collect. Sometimes it shows up messy and human, in the form of a woman who refuses to be hurried and knows where the light switch is. Sometimes it shows up with a badge. Sometimes it shows up as a letter tucked behind a recipe, reminding you to feed yourself before you feed anybody’s fantasy.

I turned off the kitchen light and the house held me the way a good verdict holds: not vindictive; correct. The kind of rightness that doesn’t need a witness or a gavel, because the room knows and the walls agree. I went upstairs, past the gallery of little framed deeds and larger decisions, and when I lay down, I did not dream of envelopes or ultimatums or women who sell spirituality by the hour. I dreamed about keys—how they sound when they meet a lock that was always theirs, and how a door opens like a quiet apology to the person who owns it.

Balance restored. Interest collected. Light on. Door open. Home.

What I didn’t tell Brad—what I didn’t tell anyone until much later—was how the file took shape. It didn’t arrive whole. It accreted. The way a shoreline builds from the smallest insistences of tide.

It began with a receipt.

A boutique in Greenwich billed to Brad’s personal card for a candle a person could either light or pay rent with, depending on her priorities. He presented it as a gift “for the house,” something Madison had recommended for “clearing energy.” I said thank you because I was raised to, then took a photo of the receipt because Rose raised me, too.

At noon the next day, a sandwich wrapper in Brad’s passenger footwell from a deli in Scarsdale—three blocks from Dr. David Peterson’s practice. On Thursday, a spa charge posted out of Sedona; on Friday, the white BMW appeared reflected in Brad’s sunglasses on a selfie he took by accident. One detail at a time, the story knocked politely and then walked in.

On my lunch hours I visited places most people forget exist until they need them: the County Clerk’s office with its humming fluorescents and its shelves of paper that could save or ruin a Tuesday; a library media room where public terminals remember more than anyone suspects; the bland little lobby of a leasing office in White Plains whose manager liked talking about pets. I asked only questions anyone is entitled to ask. Rose taught me that you don’t need keys when you know which doors are public.

In the evenings, I brewed tea and built timelines. Not because I’m paranoid. Because I am thorough. And because men like Brad believe the plural of anecdote is intimacy. It isn’t. It’s evidence when you put it in order.

What surprised me most wasn’t the pattern. It was the quiet inside me while I mapped it. Not the dead quiet of resignation—this wasn’t surrender. It was the careful hush of a woman turning on lights one by one in a house where she already knows the layout.

When the pattern found its shape, I printed two copies. One lived in the safe with the deed and the original will. The other I kept in a plain folder on the second shelf of my office bookcase between two criminal treatises I knew Brad would never open. He’s the sort of man who believes law books can infect him with responsibility if he cracks the spine.

The night of the confrontation, after the BMW screamed out and the candles coughed into darkness, I stayed at the kitchen island and let the clock count me back into my own body. I washed the bowls because they were there and because water and soap have the sacrament of a reset. Brad stood uselessly where men stand when their scripts run out—hands on granite, head bowed as if prayer might answer questions he never asked.

“Do I have to move out tonight?” he asked finally, the voice of a teenager who has mistaken leniency for love his entire life.

“No,” I said. “You have to move out when our lawyers agree on paper that keeps us from repeating ourselves. You will not bring anyone here. You will not use the garage. You will return the key, and I will change the code.”

He nodded, slow, like a man learning he does not speak the local language after months of assuming everyone understood him.

In bed, I stared at the ceiling and made lists until sleep arrived with its sensible shoes. In my dream, Rose and I were at the clerk’s counter. The woman behind the glass slid us a deed, and when I signed, the pen left a trail of light.

Pretrial.

I didn’t attend because I had court that day on a contractor‑dispute case where a kitchen island had become a battleground. But Patricia texted updates the way a metronome keeps time. Melissa in navy blazer and borrowed posture; a public defender with a folder that looked like it had met the facts five minutes earlier; the litany of charges read plain into the room. Fraud. Identity theft. Tax evasion. Investigators from two counties sharing notes. No handcuffs—this was not television—but a gravity you could feel even through a phone screen.

Later, I walked out of my courthouse into a wind that smelled like cold metal. A man argued with a meter maid. A robin scolded the world on a bare branch. Justice isn’t cinematic so much as stubborn. It shows up, it clocks in, it does its chores.

On the sidewalk I thought, not for the first time, about how easily you can build a life that looks like a life, if you are willing to mortgage your soul for the down payment. I went back to the office and wrote a letter for a client whose landlord was pretending a handshake could evict a single mother. If the world insisted on pretending, I would insist on paper.

Brad’s mother called. Carol Caldwell has the gift of taking your temperature with a single sentence. “Are you eating?” she asked.

“I’m managing,” I said.

“You always do,” she said, and I couldn’t decide if it was a compliment or an indictment. Then, softly, “I’m sorry for my son. He was not raised to be a fool.”

“Most fools are self‑taught,” I said, and Carol made the noise a woman makes when a younger woman has earned a joke.

She brought me a pie—apple, lattice like a good argument—and stood in my kitchen as if waiting for absolution to rise with the steam. “You don’t owe me reconciliation,” I told her. “But you can stop apologizing for a man who is older than both of us were when we learned better.”

“I will work on that,” she said. “I’ll fail sometimes.”

“That’s allowed,” I said. “Failing at the right things is how we retire the wrong ones.”

The house began speaking to me again. Not in words. In requests. Oil the hinge on the pantry. Replace the gasket in the powder room toilet. Sand the nick on the banister where a suitcase took too sharp a corner three summers ago.

I hired a carpenter named Ruth who smelled like cedar and answered questions as if tools were a language she loved to translate. She refitted a stubborn window and taught me to set a screw without stripping it. “Pressure,” she said, guiding my wrist, “is a story you tell the material. Too much and it resists. Not enough and it ignores you.”

After she left, I practiced with scrap wood until the movement felt like a sentence my hands had always wanted to speak.

Keys & Deeds, the clinic, grew because need is a perennial crop. We added a Saturday session for women who worked nights and could not spare a weekday hour. We set out coffee strong enough to steady hands and a tray of store‑bought cookies that always, inexplicably, made people cry.

On a rain‑polished morning, a woman in a red windbreaker sat in the back row with her arms crossed like a drawbridge and her eyes so tired I wanted to take off my own and lend her the rest of the way. She waited until we were stacking chairs. “My name is Teresa,” she said, and the bridge lowered an inch. “I think my son put his girlfriend on my deed.”

We pulled her file from a tote full of files that felt suddenly like a holy thing to carry. The “girlfriend”—caregiver on weekdays, predator on weekends—had talked Teresa into a quitclaim with the promise of “protecting assets.” Protecting, in this case, meant redirecting. I showed Teresa the line where the harm lived. I called a former colleague who owed me a favor. Patricia drafted something with teeth. Jennifer traced a transfer that wasn’t as clever as the thief imagined.

Three weeks later, we slid a corrective deed across a church‑basement table to a woman whose hands shook with relief, and I thought, perhaps, this is my favorite sacrament after all: the passing of paper that grows a spine.

Another night, an older woman named Mrs. Samuels arrived in tears over a reverse mortgage she didn’t understand. Her late husband had signed when the roof leaked and the pension didn’t stretch. The terms were a maze designed so that poor lighting would look like a choice. We set up a meeting with a nonprofit counselor; we refined a plan. The lender’s representative frowned at me in a conference room that smelled like carpet cleaner and fear. I smiled the way Rose taught me to: politely and with references. By the end of the month, Mrs. Samuels had a modified agreement and a roof that no longer carried weather into her sleep.

We did not win every time. Sometimes the law is a door you can only knock on, and the person on the other side has decided long ago that your knuckles don’t count. On those nights, we walked women to their cars and held their hands and sat in my own later with a glass of water and let the losses pass through me like storms. You cannot hold weather. You prepare for it. You build for it. You wait it out together.

In February, a developer named Arthur Vale tried to dress greed as philanthropy two streets over. He promised “affordable condos” on a corner where maples had stood longer than the realtor hawking the plan had been alive. He shook hands with the church ladies and said “community” as if it were a password.

I attended the zoning meeting with a folder and a smile. Vale’s lawyer wore a suit the color of a weak alibi. When he misquoted a setback provision, I corrected him with a tone fit for a dinner table and a citation fit for court. When Vale insisted the plan preserved “historic character,” I submitted photos of the 1912 porch he meant to raze and the 1913 porch he had already knocked down across town.

“You can’t be everywhere, Ms. Caldwell,” Vale said afterward, his grin an old fence in need of repair.

“Correct,” I said. “But I can be here.”

The board tabled the vote. The maples kept their jobs a little longer. Sometimes victory looks like a postponement. Sometimes that’s exactly enough.

Brad texted less and lived more. He sent a photo of his first attempt at meatloaf—burnt glaze, misshapen courage—and added, I’m learning. I sent back a thumbs‑up and a tip about onions. I did not add that grief is often a kitchen skill: chop, simmer, taste, adjust.

In April he asked if I’d consider speaking to one of his clients, a widow nervous about a title transfer. It was a proper request, routed through my office, with fees and boundaries. I said yes. We met in a small conference room where spring pushed through the window in skinny green pencils. I explained life estate options. The widow smiled in that way people do when language finally fits their mouth. Brad thanked me with professional gratitude and nothing extra. We were learning the choreography of two people who once shared a bed and now share a county.

A letter from Rose again, this one lodged in a folder with our old Monopoly money—two hundreds, three fifties, a handful of cheerfully lying fives. The letter was shorter, written the day I started law school.

Harper,

Being in the right will never replace being prepared. If you have to choose, be prepared. But you don’t have to choose as often as men will tell you you do.

— R.

I tucked it back and laughed alone in the kitchen like a person who has found the exact screw that turns the whole machine.

On a bright, raw morning in May, a woman with a microphone waited outside our clinic, hair sprayed into hurricane readiness and smile sharpened for blood. “Ms. Caldwell,” she called, “how does it feel to bring down a local yoga teacher?”

“Unearned,” I said, and kept walking. “She brought herself down. We brought documents.”

“Is it true you coordinated a—” she searched for the word “—posse?”

“It’s true women text,” I said.

It aired that night with a lower‑third chyron that turned nuance into a hashtag. My voicemail filled with strangers. Some wanted advice. Some wanted a fight. I changed the message to say we could not answer everything and meant it. We are not the Internet. We are a basement with good coffee and better pens. We were built for scale only in the sense that kindness scales if you stack it carefully.

Summer found me. I watered the fern without drowning it. The maple pulsed high and green. The house exhaled cool at dawn and held heat midafternoon in the floors like a cat does alongside a window. I learned the names of the neighbor’s children. I learned I prefer real lemonade to any other kind of sweet.

One evening, I set the table for myself with the good plates because I was a person who deserved setting. I ate peaches over the sink like a teenager and then ate another like a woman who can afford juice on her wrists. Outside, someone’s radio played Springsteen soft and hopeful. My phone buzzed—Victoria: We got funding. A grant for Keys & Deeds, enough to replace folding chairs with real ones. Enough to print materials without begging the church photocopier to keep its toner a little longer. I sat down and cried on the good plate and didn’t scold myself once.

I saw Melissa only one more time before sentencing. In a hallway, outside a courtroom, where the air tastes permanently of worry. She wore a thrift‑store blouse and the eyes of someone who has met her reflection in unflattering light.

“Harper,” she said. Not “Ms. Caldwell.” My name, like a bruise you press to test what still hurts.

“I hope you get help,” I said, because Rose would have wanted me to mean it. “And I hope you start telling yourself the truth before you tell it to anyone else.”

She opened her mouth to say all the things people say when they want to be forgiven without having to be changed, then closed it. “You were never going to give him that house,” she said, the tiniest spark of the old arrogance flickering for air.

“He was never going to take it,” I said, and watched the grammar of that sentence confuse her. Ownership is not a feeling. It is a record.

Sentencing came like a calendar item we all wanted to reschedule. The judge was steady. The charges were what they were. Restitution in numbers that would have sounded imaginary in any other room. Probation with teeth. The kind of supervision that turns every errand into an accounting. She walked out not in chains but in something finer: accountability.

I did not feel triumph. I felt the relief of a room set back the way it was before someone moved the furniture while you were out.

Autumn again. The maple replayed its piece in gold. Keys & Deeds moved from the basement to the community center with windows that made everyone braver. We painted one wall a blue that looked like confidence you can lean on. We bought pens that didn’t skip. We laminated a checklist that began with “Breathe” and ended with “Make copies.”

Brad sent a photo of a small trophy: two years at his new firm, a client retention rate that would have impressed his old boss. Beneath it: Thank you for not breaking me on purpose. I typed back: Thank you for not asking me to. Then I put my phone down and watched a squirrel bury a walnut with the intensity of a monk copying scripture.

On the second anniversary of the envelope, I woke early and drove north as far as I could before the reservoir made the road curve back at itself. I parked and walked a trail where leaves fell with a hush that felt like humility. I sat on a flat rock and took out Rose’s letters and read them while the water watched. When the sun cleared the trees, I said aloud, to the empty morning and to the woman who taught me to use silence like a tool, “I did what you would have done, and then I did what I wanted, and both were the same thing.”

A heron lifted off the shallows with that prehistoric patience that feels like blessing and biology all at once. I went home and made meatloaf—more onion because the air had teeth, double glaze because Patricia and Victoria and Jennifer were coming and they always deserve seconds.

We ate and told new stories. Not the Madison story; that one had shrunk to size. We told the story of the woman who almost lost her duplex until a clerk in Yonkers found a microfilm nobody had asked about in eleven years. We told the story of the teenage girl who translated a mortgage explanation for her mother and corrected my Spanish with the dignity of a future lawyer. We told the story of the grant that turned into three grants because competence and evidence are contagious when properly displayed.

“Do you ever miss him?” Jennifer asked as we stacked plates.

“I miss the version of us we thought we had,” I said. “But she never existed, and I don’t grieve fiction like I grieve people.”

Patricia nodded like a judge. Victoria poured more wine. Outside, the maple prepared its next costume change.

There is a drawer in my kitchen that holds what my mother called “randoms”—rubber bands, battery‑less flashlights, lighters that may or may not work, three Allen wrenches that fit no furniture I own. I cleaned it out on a quiet Tuesday and found, underneath a stack of takeout menus from restaurants that had already become someone else’s dream, a Polaroid Brad and I had taken the week we moved in. We were sweaty and smug, holding a paint roller like a baton we were about to pass badly. Behind us, the wall was primer white and possibility.

I thought about throwing it away. Instead, I slid it into the back of the recipe binder behind Rose’s banana bread, because life is not neat, and memory is not an enemy. It is a map you consult with skepticism and affection.

That night, the house creaked in its honest places. I locked the door without looking, because my hand knew its work. I stood in the pantry and smiled at the hinge that no longer complained. I turned off lights and the dark came down not like a curtain, but like the hand of someone you trust, settling on your shoulder, saying, You did fine. Go to sleep.

In bed, I drafted a new checklist for Keys & Deeds. The final line read, in bold, as if I needed reminding: You are allowed to own what you own.

Morning would come with coffee and emails and a woman at the community center who needed help untangling a title from a mess a cousin left behind. Afternoon would bring a run by the reservoir and a stop at the deli where the owner calls me Counselor even when I’m wearing sneakers. Evening would carry the kind of quiet that is not absence, but evidence—of work done, of rooms held, of a life standing upright inside the frame built to hold it.

Balance restored. Interest collected. Not once, but as many times as it takes.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load