I never thought I would spend Easter Sunday in an emergency room lobby with a wine‑soaked shirt, blood drying on my forehead, and a tiny American flag magnet staring back at me from the vending machine.

But there I was, sinking into a cracked vinyl chair under buzzing fluorescent lights, Sinatra mumbling from an old speaker in the ceiling, the smell of burnt coffee and industrial cleaner in the air.

My phone vibrated in my palm. I opened a new text, typed four words, and hit send:

Phase one is complete.

I slid the phone back into my pocket, leaned my head against the cool white wall, and felt a slow, bitter smile pull at the side of my mouth. My shirt was ruined, my head was throbbing, and my family had just detonated itself over two empty bedrooms.

Honestly? It was still better than the future my son and his wife had in mind for me.

Let me back up.

My name is Robert Chen. I am sixty‑three years old, retired from my accounting practice for just over three years. I live alone in a three‑bedroom ranch house in Bellevue, Washington, a quiet street with maple trees, kids on scooters, and more Teslas than I can count parked in driveways.

We bought the house back in 1992 for one hundred seventy thousand dollars, which felt like a small mountain at the time. Today, the place is worth close to one point eight million. The mortgage has been paid off for years. The roof is solid, the plumbing behaves, and the lawn is the only thing that really demands attention.

My wife, Sarah, died five years ago after a long illness. I still cannot say the word they wrote on her chart without feeling like I am swallowing glass. The chemo, the hospital rooms, the way her hands got smaller in mine every month — I carry those details in a locked drawer in my head. I take them out when I need to remember why I am still here.

Since she passed, it has just been me and the house.

Three bedrooms. One for me, one I turned into a small office, and one that has become a guest room that never gets used. A king bed that feels too big, a kitchen that still smells like garlic and rosemary on rainy days, and a quiet that hums in the walls at night.

People hear that and assume I must be lonely. I am not. I get lonely sometimes, sure. But loneliness and being alone are not the same thing. One feels like drowning. The other feels like breathing.

My son, Daniel, is thirty‑two. He works in pharmaceutical sales, drives a white Tesla with a vanity plate that is supposed to be clever but mostly looks expensive, and lives about forty‑five minutes away in a subdivision outside Seattle. He married a woman named Britney ten years ago. They have two kids, Emma and Lucas, eight and six.

On paper, it is the kind of life people post on Instagram. Matching Christmas pajamas, pumpkin patch photos, backyard inflatable pools. I am in maybe one out of every twenty pictures.

I see the kids once a month if the stars align and nobody has soccer, dance, or a last‑minute sales meeting. Sometimes it is less. I tell myself that is just how things are these days, that busy is the new normal.

Most holidays, though, still happen at my house.

Sarah was big on tradition. Easter hams, Thanksgiving turkeys, Fourth of July cookouts with cheap flags from the supermarket stuck into flower pots on the porch. At some point, we decided that everyone would just come to us. Our kitchen was bigger; our driveway could handle more cars. After Sarah died, I kept the tradition going because pretending nothing had changed was easier than staring at the empty chair across from me.

This Easter Sunday started like all the others. I woke up early, made coffee, and flipped on the morning news with the sound low. Outside, a couple of neighbors had already put little plastic eggs along their front walks for the neighborhood kids. One house down the street had a big wooden sign with a bunny wearing an American flag bandana. I caught my reflection in the window and almost laughed. Gray hair, flannel shirt, mug in hand, standing in a house that looks like it belongs to someone who still has a wife.

Old habits die hard.

Daniel had called on Tuesday to confirm I was hosting dinner. He did not ask if I was up for it. He just said, ‘So, we are doing Easter at your place Sunday, right?’ as if there were no other options.

I said yes because that is what I always say.

Saturday, I did the shopping. Leg of lamb. Potatoes. Carrots. Fresh rosemary. Brown sugar. Yeast and flour for Sarah’s hot cross buns. She had written the recipe on a yellowing index card twenty‑five years ago, the ink faded around the edges from flour and oil. I still keep that card in a little plastic sleeve like it is a rare baseball card.

I spent the afternoon kneading dough and marinating the lamb. The house filled with the smell of yeast, sugar, and garlic. I put pastel paper napkins on the table, the same ones Sarah would buy on clearance every year in January and save for Easter. I set out the good china, the set we got as a wedding present from her parents. I tucked a chocolate egg into each napkin ring for Emma and Lucas.

Every step felt like a small promise: I can still do this. I can still be the center of this family.

Around three in the afternoon, Daniel’s Tesla slid into my driveway like a spaceship docking. I watched from the kitchen window as they climbed out. Emma immediately started bouncing, pointing at the plastic eggs in my front yard. Lucas was glued to a tablet, only moving when Daniel nudged him forward.

Britney stepped out last, sunglasses on, hair perfect, carrying an oversized bottle of red wine tucked against her designer cardigan. It was the kind of bottle you buy when you want someone to notice the label.

Britney only brings expensive things when she wants something. I learned that the hard way.

I wiped my hands on a dish towel, took a breath, and opened the front door.

‘Dad.’

Daniel gave me a quick hug, his hand already sliding back toward his pocket like he was afraid his phone might feel neglected.

‘House looks great,’ he said.

‘Thanks, son. Kids, come give Grandpa a hug.’

Emma barreled into me with all the enthusiasm of an eight‑year‑old hopped up on sugar and holiday anticipation. Lucas followed with a more reserved squeeze, eyes darting toward the living room where the TV lived.

At least with them, it still felt genuine.

‘Grandpa, we had an egg hunt at school,’ Emma said in one long breath. ‘I found eleven eggs. Lucas only found five.’

‘That is because the teacher hid them where Emma could see them,’ Lucas grumbled.

I laughed, ruffled his hair, and let their voices fill the doorway.

Britney leaned in and kissed my cheek, her perfume hitting me a second later. Too strong, too sweet, like a candle in a small room.

‘Robert, thank you so much for having us,’ she said. ‘This wine is from Napa. It is supposed to be exceptional.’

‘You did not have to bring anything,’ I said.

‘Oh, I insist.’

She set the bottle on the counter with a little smile that did not make it anywhere near her eyes.

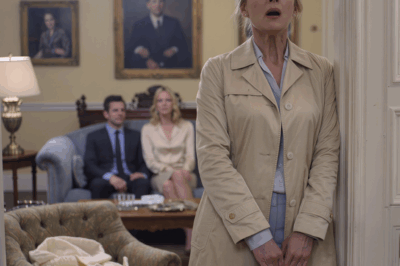

We moved into the living room while the lamb finished roasting. I had set the dining table already, but Daniel wanted to ‘chat’ first. He dropped onto the couch, phone face‑down on the coffee table for once. Britney perched on the edge of the armchair across from him, legs crossed, hands folded too neatly in her lap.

That should have been my first warning. Daniel never wants to chat.

Usually, he is half in a conversation and half in his email, talking about quarterly numbers, complaining about his manager, scrolling while he talks. But today, he was focused, present. Every few seconds, he flicked his eyes toward Britney like they had practiced whatever was coming.

‘So, Dad,’ he started.

I felt my stomach tighten.

‘Brit and I have been talking about your situation.’

There it was. My situation.

Living here alone. This house is…’ he looked around like a realtor at an open house, ‘it is a lot for one person to maintain.’

I kept my face neutral, my voice steady.

‘I manage just fine. The house is paid off. Maintenance is not bad.’

‘But you are getting older,’ Britney said, her tone soft but her eyes sharp. She leaned forward, elbows on her knees. ‘We worry about you. Falls, medical emergencies. What if something happens and no one is here?’

‘I have my phone. I have neighbors who check in. I am careful.’

Daniel and Britney exchanged another quick glance. I recognized it. That silent, here we go look.

‘We have a proposal,’ Daniel said.

Someone once told me that when your adult children say they have a proposal, it is never going to be something like, we are paying off your car or we bought you a vacation. It is always about you changing your life to make theirs easier.

‘Britney’s parents just retired,’ he went on. ‘They sold their place in Spokane last month. They are looking for somewhere closer to us, but the market is insane right now. Prices, interest rates, the whole thing.’

‘Congratulations to them,’ I said, because it seemed like the kind of thing a reasonable person would say.

‘They are good people, Dad,’ Daniel said quickly. ‘Really active, really helpful. Britney’s mom was a nurse. Her dad taught shop class for thirty years. They love the kids. They would be a huge help.’

Britney jumped in like she had been waiting for that cue.

‘We were thinking,’ she said, ‘you have those two extra bedrooms just sitting empty. What if my parents moved in? They could help around the house, keep you company, and honestly, it would be cheaper for everyone. They would pay you rent, of course.’

There it was. Neat. Practiced. Polished.

‘You want your parents to move into my house,’ I said.

‘It is perfect,’ Britney said, her voice going a little higher. ‘You would not be alone anymore. My mom could help with cooking and cleaning. My dad is handy; he can fix things. And we would all be closer together as a family.’

I looked at Daniel.

‘And what do you think about this?’

He lifted his shoulders in a practiced shrug.

‘I think it makes sense, Dad. Practical. You would have built‑in help. They would have an affordable place in a great neighborhood. Win‑win.’

The oven timer went off in the kitchen. The lamb, right on schedule. Saved by the bell.

‘Let me check on dinner,’ I said.

I stood, walked into the kitchen, and closed my eyes for five slow seconds.

Breathe. Stay calm.

This was exactly what Thompson said would happen.

Three months earlier, my financial adviser had called me about a flagged login attempt on one of my retirement accounts. Someone had tried to get in. They had my birth date, my mother’s maiden name, even Sarah’s maiden name. They got far enough that the bank froze the account and sent up flares.

The IP address traced back to an address in Daniel’s suburb.

I did not confront him. Not right away. Instead, I called Richard Thompson, the estate lawyer who had handled Sarah’s will. Thompson is in his fifties, gray at the temples, always wearing the same brown leather shoes and navy blazer. He used to work in elder law before moving fully into estates.

He knew exactly what this smelled like.

‘Robert,’ he had said over coffee at a diner near his office, the kind with American flags in tiny plastic holders at each booth and iced tea that tastes like melted sugar, ‘I see this pattern every week. Adult children get impatient about inheritance. They test boundaries. Little things, like trying to log into accounts or asking you to add them as joint owners. Then they start suggesting you cannot live alone, that you need “help” managing things. And then it escalates.’

‘What do I do?’ I asked.

‘We set up safeguards,’ he said, ‘and we document everything.’

Over the next few months, we went to work.

First, Thompson arranged a full cognitive assessment with a geriatric specialist. I passed with scores that made the doctor joke I could probably still be doing tax returns in my sleep. We had it all in writing, signed, dated, stamped. Proof I was mentally sharp. No dementia, no impairment.

Second, we updated my will. Ironclad language, multiple witnesses, and very specific instructions about what would happen if anyone tried to contest it.

Third, we set up a living trust and moved the house and my major assets into it with protections that made it very hard for anyone to pry them open.

Fourth, and this was all Thompson, we installed small, discreet cameras in my living room, dining room, kitchen, and at the front door. Legal in my own home, clearly within my rights.

‘If they are planning something,’ Thompson said, stirring sugar into his coffee, ‘they will eventually say it out loud. People who think they are entitled to something love to justify themselves on tape.’

When the bank pulled the IP logs and Thompson compared them with Daniel’s address, his expression had gone flat.

‘Do not accuse him yet,’ he said. ‘Wait. Let them talk. Let them show you who they are.’

So I waited.

In the kitchen, I checked the lamb. Perfect. Browned, sizzling, the thermometer sliding in at exactly the right temperature. I spooned juices over the top, set it on a cutting board, and took a breath.

This was the moment where the story I had been telling myself about my son could either survive or die.

I carved the lamb, plated the vegetables, and called everyone to the table.

Dinner started fine. The kids talked about school and cartoons. Emma told me about a class project where they had drawn the American flag and recited the Pledge. Lucas was obsessed with some video game I did not understand. I asked Daniel about work, and he gave me a few surface‑level complaints about his boss.

Britney complimented the food. Twice.

If you watched it with the sound off, it would look like any other family dinner in any other three‑bedroom house in America.

Then Daniel set down his fork.

‘So, Dad,’ he said, ‘about my in‑laws.’

Here we go, I thought.

‘Have you thought about it?’

‘I have,’ I said.

I set my fork down too. My hands were steady.

‘I appreciate that you are concerned,’ I said, ‘but I am not interested in having roommates. I like my privacy. I like my routine.’

Britney’s smile twitched like a glitch in a screen.

‘Roommates?’ she repeated. ‘They are family, Robert. They would be your family.’

‘I have met them twice,’ I said.

Her voice sharpened.

‘But you have all this space,’ she said. ‘Two empty bedrooms, your own bathroom. What are you even using them for?’

‘That,’ I said, ‘is my business.’

Daniel leaned forward.

‘Dad, be reasonable,’ he said. ‘You are sixty‑three, living alone. What happens when you are seventy? Seventy‑five? Eventually, you are going to need help.’

‘Then I will hire help,’ I said calmly. ‘Or I will move to a retirement community. On my terms.’

‘Those places cost a fortune,’ Britney said, actually laughing. ‘Why spend money on strangers when you could have family here?’

‘Because it is my money,’ I said, ‘and my house.’

The room went quiet. Emma stared at her plate. Lucas peeled the foil off his chocolate egg with surgical focus.

‘Kids,’ I said gently, ‘why don’t you two go find something to watch in the living room?’

Emma grabbed Lucas’s hand without a word. They disappeared, the sound of cartoons floating back a minute later.

Once they were gone, Daniel’s expression hardened.

‘This is unbelievable,’ he said quietly. ‘You are being selfish.’

There it was. The word.

‘We are trying to help you,’ he went on, ‘and you are acting like we are asking for a kidney.’

‘I said no,’ I replied. ‘That is not selfish. That is a boundary.’

Britney pushed back from the table. Her face was flushed, whether from the wine or the anger it was hard to tell.

‘Do you know what our mortgage payment is?’ she demanded. ‘Do you have any idea how much child care costs? We are drowning, Robert. And you are sitting here in a nearly two million dollar house like some feudal lord, hoarding space.’

‘I am not hoarding anything,’ I said. ‘I live here.’

‘You live here alone,’ she shot back. ‘Sarah has been gone for five years. When are you going to move on and think about someone other than yourself?’

That one cut. I felt it. But I kept my face neutral.

Daniel reached for her arm.

‘Brit, calm down,’ he said.

She shook him off.

‘No, I am tired of this,’ she said. ‘My parents are good people. They helped us with the down payment on our house. They babysit whenever we ask. And now they need help. And your father cannot even spare two empty bedrooms.’

‘I said no,’ I repeated.

‘Why?’ she demanded. ‘Give me one good reason why.’

‘Because I do not want to,’ I said.

Sometimes the truth is that simple.

Her hand snapped toward the bottle of wine on the table, fingers closing around it before I could even process the movement.

For a split second, I thought she was just going to pour herself another glass.

Instead, she grabbed her half‑full wine glass and flung it at me.

Red wine exploded across my face and chest. I heard the shatter before I felt the sting. The glass hit the edge of my plate and broke, one sharp shard catching my eyebrow.

Warmth bloomed above my eye. A thin line of blood slid down into the wine soaking my shirt.

For a second, nobody moved.

‘Britney!’ Daniel shouted, stumbling to his feet.

I reached up and touched my forehead. My fingers came away red and sticky with wine and blood.

Britney stared at me, chest heaving, eyes wide like she could not believe what she had just done.

I could. Because this is what entitlement looks like when it hits a wall.

I stood slowly.

‘I think,’ I said quietly, ‘I need to go to the hospital.’

‘Dad, I am so sorry,’ Daniel said. ‘She did not mean—’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘she did.’

I walked around the table, past Britney’s chair. She flinched when I stepped near her, like I might throw the glass back.

‘I need medical attention,’ I said. ‘So I am going to drive myself to the ER. You should all leave.’

In the bathroom, I grabbed a clean towel and pressed it to my forehead. The cut was small, but head wounds bleed like a horror movie. I caught my reflection in the mirror: wine, blood, gray hair, an Easter tie with little cartoon eggs Sarah had bought me fifteen years ago.

For a moment, I thought about the camera hidden in the air vent above the dining room table.

Then I thought about the IP logs from Daniel’s suburb, and the way he had said your situation.

The towel turned pink as I pressed it to the cut.

Perfect, I thought.

I grabbed my keys from the hook by the front door — the same hook where a small metal house key hangs that I have not given to anyone new in five years — walked past the living room where the kids were frozen on the couch, eyes round, and stepped out into the chilly April air.

‘Dad, wait,’ Daniel called from the doorway.

‘There is nothing to talk about,’ I said without turning around. ‘Your wife just assaulted me in my own home. I need to get this looked at. Please leave my house.’

I got into my car, set the towel back against my eyebrow, and pulled out of the driveway.

At the first red light, I took my phone out, opened my messages, and typed the four words I had promised Thompson I would send if things ever went this far.

Phase one is complete.

I hit send and watched the little blue bubble go through.

By the time I walked into the ER waiting room, Thompson had already texted back.

On my way. Do not talk to Daniel. Document everything.

The ER on Easter Sunday was busy, but not chaotic. A toddler with a plastic bunny headband sobbing over a sprained wrist. A teenage boy holding a towel to a bloody nose, his baseball jersey streaked with dirt. An older woman with curlers still in her hair and a church bulletin clutched in one hand.

I checked in at the desk, explained what had happened in the blandest terms possible — family argument, glass thrown, cut on forehead — and took a seat under a television playing a rerun of some old baseball game. On the screen, a player adjusted his hat, the little American flag patch on the side catching the light.

The nurse called me back faster than I expected. They took my blood pressure, asked me the usual questions, then had me sit on a bed in a curtained‑off room. A thin trail of dried wine snaked down my collar.

Thompson pushed through the curtain fifteen minutes later, slightly out of breath. He looked at my forehead, at the swirl of dried red on my shirt, and let out a low whistle.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘they certainly saved us some time.’

I told him the whole story, every word I could remember. The mention of my situation. The proposal. The two empty bedrooms. The way Britney had framed the whole thing as me hoarding space. The glass arcing through the air.

Thompson took notes on his phone, his face going hard in that way lawyers have when the facts line up exactly the way they hoped and still make them angry.

‘The kids,’ he asked. ‘They were not in the room when she threw it?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘They were in the living room.’

‘Good,’ he said. ‘You did the right thing leaving. And the cameras?’

‘They should have caught everything.’

‘All right.’ He slipped his phone into his pocket. ‘I am going to call the police. You want to press charges, yes?’

We had talked about this, late one night over decaf coffee at my kitchen table.

If things escalated to physical aggression, we had options: police reports, restraining orders, a very clear line in the sand. But we both knew once that line was crossed, there was no going back to the illusion of normal.

I looked down at my ruined shirt, at the faint outline of a chocolate bunny on the paper napkin still tucked in my pocket for Lucas.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I want to press charges.’

‘Okay,’ Thompson said. ‘Then we do this right.’

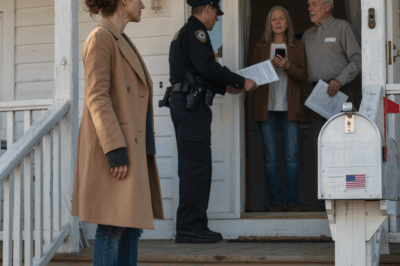

Within an hour, two officers stepped through the curtain — a young male officer with tired eyes and a female sergeant whose posture said she had been doing this for a long time.

They introduced themselves, asked me to tell them what had happened. I told the story again. They took photos of my forehead, asked if they could take my shirt as evidence. The male officer slipped it into a paper bag, sealing it carefully.

‘Do you feel safe going home tonight, Mr. Chen?’ the sergeant asked.

‘I do,’ I said. ‘But I want to make sure my daughter‑in‑law cannot come near me or my house.’

She nodded.

‘We can start with the assault charge,’ she said. ‘Given your age and the family relationship, the prosecutor may consider additional factors. There are enhanced penalties in this state when older adults are targeted.’

She did not say the words elder abuse, but they hung in the air.

A doctor came in, cleaned the cut, and sealed it with liquid stitches. It was minor, he said. No concussion. No permanent damage.

He was wrong about that last part.

By the time I walked out of the ER, Thompson had already spoken with a contact at the precinct. A patrol car had gone to Daniel’s house. Britney had been arrested, then released a few hours later with conditions. No contact with me. No coming near my home. Promise to appear in court.

When I slid back into my car, I glanced at my phone.

Twenty‑nine missed calls from Daniel.

I watched the number for a moment, the way it sat there like a dare. Then I locked the screen and drove home.

Thompson followed me to the house. We went straight to my small office, the one that used to be Sarah’s sewing room. I woke up the computer, opened the security software, and pulled up the camera feeds.

Living room. Dining room. Kitchen. Front door.

We scrolled back to that afternoon.

There we all were, frozen around the table. I watched myself walk into the kitchen. I watched Daniel lean toward Britney. I watched her roll her eyes.

We watched the entire conversation unfold in grainy high‑definition audio and video. My situation. My living alone. The proposal. The insistence that I was hoarding space. The wine glass. The arc, the impact, the blood.

When it was over, Thompson sat back, his jaw tight.

‘This is excellent evidence,’ he said. ‘Clear, unprovoked aggression. You stayed calm. You removed yourself. She looks like she lost control when you did not give her what she wanted.’

‘What happens now?’ I asked.

‘Now,’ he said, ‘the police investigate. The prosecutor reviews the case. She will have to go to court. We will ask for a restraining order. And in parallel, we deal with the bigger issue: the financial piece.’

‘The account access,’ I said.

He nodded.

‘I will file a formal complaint with your bank and with the police,’ he said. ‘Attempted financial exploitation of an older adult. Even if the prosecutor does not charge it, we want it on record. At the very least, the bank will lock down your accounts so tightly that Daniel could be standing in the lobby with your passport and they would still call you first.’

He paused.

‘We also update your will again,’ he added. ‘We make it very clear that any attempt to challenge your capacity or interfere with your finances will cost them whatever they think they are getting.’

‘What about the kids?’ I asked quietly.

Thompson’s face softened.

‘We set up separate education trusts for Emma and Lucas,’ he said. ‘Money they cannot touch until they are twenty‑five, managed by an independent trustee. That way, no matter what Daniel does, the kids will be taken care of.’

That felt right. The kids had done nothing wrong except be born to parents who were learning the wrong lessons about entitlement.

Thompson left a little before ten that night, his briefcase heavy with printed copies of statements and reports. I stood in the doorway, the cool night air washing over me.

Inside, the house smelled like rosemary, garlic, and cheap fear.

The dining table was still set, plates half‑finished, glasses tipped at odd angles. A thin line of red wine dried on the wall behind my chair. The security camera’s tiny light blinked steadily from the corner.

On the hook by the door, my house key hung alone.

My phone buzzed again on the hall table.

Daniel.

I let it ring. It went to voicemail. A second later, a text came through.

Dad, please call me. Britney feels terrible. We need to talk.

I turned the phone over so the screen faced down.

I slept badly that night, waking every couple of hours to the phantom sound of a glass shattering. Each time, I walked to the front door, checked the deadbolt, and glanced at the small key on the hook.

I did not owe anyone a spare.

The next morning, the detective assigned to the case called to confirm my statement and to let me know that Britney had been formally charged with misdemeanor assault, with the possibility of enhanced penalties given my age.

‘You will get a notice in the mail with the court date,’ he said. ‘If she contacts you, call us or call 911 immediately.’

He hesitated.

‘Your son says he wants to make things right,’ he added.

‘I am sure he does,’ I replied. ‘But right now, the only thing that needs to be right is the paperwork.’

Tuesday, Thompson filed the financial complaint. The bank froze my accounts for seventy‑two hours while they investigated. It was inconvenient, but necessary. I had a small checking account at a different bank for emergencies. Sarah had insisted on it years ago.

‘Never put all your eggs in one basket, Bobby,’ she used to say, tapping the side of her nose. ‘Especially if that basket is run by men in suits.’

I could almost hear her saying it while I stood in line to withdraw some cash.

Wednesday, the detective interviewed Daniel.

According to Thompson’s contact at the department, Daniel admitted he had tried to access my account ‘to check on Dad’s financial health.’ He said he was worried about me. He mentioned concerns about ‘cognitive decline.’

That phrase, in particular, twisted something deep in my chest.

He knew I had passed the assessment. I had told him myself, proud and a little smug, the day I walked out of the specialist’s office. He had smiled, clapped me on the shoulder, and said, ‘See? You are fine.’

And then, months later, he sat in a room with a detective and claimed he was worried about my mind.

Sometimes betrayal is not a single blow. Sometimes it is a series of tiny cuts that finally hit a vein.

Thursday, Thompson and I went to the courthouse to request a restraining order.

We sat in a small courtroom with beige walls and a flag in the corner, watched the judge thumb through our file. Photos of my forehead. A printout of the account logs. A transcript from the security footage. A copy of the cognitive assessment.

‘Mr. Chen,’ the judge said, peering over his glasses, ‘do you believe your daughter‑in‑law is a danger to you?’

‘I believe,’ I said, ‘that when she does not get what she wants, she loses control. I do not want her near me or my home.’

He nodded once.

‘Restraining order granted,’ he said. ‘No contact, direct or indirect. No coming within one hundred yards of his person, residence, or place of work.’

He glanced at Daniel’s name on the paperwork.

‘As for your son,’ he added, ‘I am not making an order at this time. But Mr. Chen, you have the right to enforce your own boundaries in your home.’

I walked out of that courtroom feeling both heavier and lighter.

Friday afternoon, my doorbell rang.

I checked the camera feed before opening the door. Daniel stood on the porch alone, hands in his pockets, shoulders slumped.

I opened the door but did not step aside to let him in.

Up close, he looked worn out. Dark circles under his eyes. Day‑old stubble on his jaw.

‘Dad, please,’ he said. ‘Can we talk?’

‘The restraining order allows you to be here,’ I said, ‘but I am not obligated to invite you in. What do you need?’

‘Britney is… she is a mess,’ he said. ‘She is doing counseling. She pleaded not guilty. The lawyer says we can maybe get this dropped if you—’

‘If I what?’ I asked. ‘If I pretend she did not throw a glass at my head? If I pretend you did not try to log into my accounts from your house?’

He flinched.

‘I was worried about you,’ he said. ‘You are alone all the time. You do not tell me things. I just wanted to see how you were doing.’

‘You could have asked,’ I said.

He looked away, jaw working.

‘We are drowning, Dad,’ he said quietly. ‘The mortgage, the car payment, daycare, after‑school programs. Everything keeps going up, and my commission checks keep going down. Britney’s parents are not in great shape either. Their place sold for less than they thought. They were counting on moving in here. We all were.’

‘There it is,’ I said.

He blinked.

‘What?’

‘You were counting on my house,’ I said. ‘On my space. On my life. Not asking. Counting.’

‘I just thought…’ He trailed off.

‘You thought I would fold,’ I said. ‘That I would be so afraid of being alone I would let you turn my home into your safety net. You thought you could talk me into surrendering my independence one “reasonable” suggestion at a time.’

‘You are being dramatic,’ he said.

I pulled a folded paper from my pocket. The latest version of my will. I had made a point of carrying a copy the last few days.

‘Do you know what this is?’ I asked.

He rolled his eyes.

‘Your will,’ he said.

‘This is the document that decides what happens when I am gone,’ I said. ‘And this time, it is very clear. You are still in it. You will still receive an inheritance, as long as you respect my boundaries. But if you or Britney try to contest it, to claim I am incompetent, to interfere with my finances in any way, you get nothing.’

His mouth dropped open.

‘You would really cut me off?’ he asked.

‘You threw me away first, Daniel,’ I said. ‘Right there at my dinner table. All over two empty bedrooms.’

He swallowed, eyes reddening.

‘Britney’s parents lost a rental deposit because of this,’ he said hoarsely. ‘We were counting on them moving in here. We made plans.’

‘You made plans with my house,’ I said. ‘Without me.’

Behind him, in the driveway across the street, a neighbor was unloading groceries, pretending not to look. Word had spread already. The Chens had drama. The older man with the nice lawn and the late wife had called the police on his own in‑laws.

Let them talk, I thought. None of them were going to be in my will.

‘Get off my property, Daniel,’ I said.

‘Dad…’

‘If you want to come by again,’ I said, ‘you email Thompson forty‑eight hours ahead of time. Daylight hours only. If Britney sets one foot on this street, I will call the police. This is not a negotiation.’

I closed the door.

Through the small window beside it, I watched him stand motionless for almost three full minutes, mouth opening and closing like he was searching for the right argument and coming up empty.

Then he turned, walked down the path, and got into his Tesla.

The car slid away, silent and smooth.

On the hook beside the door, my house key did not move.

That was six months ago.

Since then, life has been a strange mix of paperwork, silence, and small, stubborn joys.

Britney’s case went to court. She stood there in a neat blazer, makeup carefully done, and listened while the prosecutor described how she had thrown a glass at a sixty‑three‑year‑old man during a family dinner because he would not hand over access to his home.

Her lawyer called it a one‑time lapse in judgment brought on by stress and wine. The judge called it unacceptable.

She pleaded guilty to a reduced charge, received a conditional discharge, two years of probation, mandatory counseling, and a stern lecture about managing anger.

The judge looked directly at me when he said, ‘Mr. Chen has the right to feel safe in his own home.’

The financial case fizzled in a more bureaucratic way. The bank’s fraud department completed their investigation, concluded that an unauthorized attempt had been made, and locked down my accounts with new protocols. The police documented it as an attempted financial exploitation incident but declined to bring separate charges.

‘These cases are hard to prosecute when family is involved and no money actually changed hands,’ the detective said. ‘But it is on record now. If he tries anything again, the pattern is there.’

That was enough.

In the meantime, I went to book club at the community center. I joined a watercolor class. I learned how to cook for one without eating leftovers for six days straight. I discovered that I actually like walking around the neighborhood at sunset, watching the sky go pink and orange behind the houses, small flags fluttering on porches.

I also learned which neighbors believe the worst version of a story first.

At the grocery store, a woman from three houses down cornered me by the dairy case.

‘I heard things got… intense,’ she said delicately. ‘You know, with your son. Family is everything, you know?’

‘Family is important,’ I said. ‘So is not getting hit with glassware in your own dining room.’

She flushed, muttered something about having to grab yogurt, and scurried away.

It is funny how quickly people forget that older adults are allowed to have limits.

Daniel called a few times a month at first. Then he switched to leaving voicemails. When I stopped returning those, the letters started.

Five letters over six months.

In them, he apologized, explained, rationalized. He described their finances in detail — their mortgage payment down to the dollar, their child care costs, the way his commission structure had changed. He painted a picture of a man doing everything right and still sinking.

He said Britney was really sorry. That she was doing counseling. That she missed me. That the kids asked about me.

He never mentioned the words account login or cognitive decline.

I read each letter once, folded it back up, and placed it in a drawer.

I did not write back.

Thompson told me something early on that I think about a lot now.

‘People will tell you that forgiving means letting them back in,’ he said. ‘That is not true. Forgiveness is not a hall pass back into your life. Sometimes it is just deciding you are not going to let their choices rot you from the inside out. You can forgive someone and still keep your doors locked.’

Two weeks ago, I went online and booked a trip to Scotland.

Three weeks. Flights into Edinburgh. A few days in the city, then a rental car up through the Highlands, out to the Isle of Skye. Sarah always wanted to go. We talked about it for years, circled brochures, watched travel shows where people drank whisky in stone pubs and hiked along cliffs over gray water.

We never made it.

I printed out the itinerary and set it on the kitchen table next to my morning coffee. The little American flag magnet that had stared at me in the ER is now on my fridge, holding up the confirmation page.

I am going alone. And I am okay with that.

The house feels different now. Less like a place I am waiting to leave, more like a place I chose to stay.

Last week, an envelope showed up in my mailbox with no return address.

Inside was a folded piece of printer paper with a drawing on it.

Three stick figures in a park. One taller, with gray hair. Two smaller, with scribbled smiles. Above them, a crooked sun and a tree. At the bottom, in carefully uneven letters, it said:

I miss you Grandpa.

I knew Emma’s handwriting instantly.

I sat at the kitchen table with that note in my hands and cried harder than I had the night Sarah died.

Not because of what I had lost, but because of what I was not willing to lose next.

It would be so easy to call the number at the bottom of the letter, to let my love for those kids haul me back into the orbit of Daniel and Britney, to trade my boundaries for weekend visits and holiday photos.

But easy is how you end up with people living in your spare bedrooms and making appointments with doctors you did not choose.

Thompson says that when Emma turns eighteen, she can reach out on her own if she wants to. The trust documents will explain everything. The education accounts are in place, separate and safe. One day, if she wants to hear my side of the story, I will sit across from her in a coffee shop and tell her everything.

She will understand or she will not. That part is not mine to control.

What I can control is this:

I am sixty‑three years old. I might have thirty more years. I might have three. However long I have left, I am going to live it on my terms, in my house, with my boundaries intact.

Sometimes family means the people who love you without a price tag attached. Sometimes it means the ones who love you conditionally, as long as you sign on the dotted line and hand over your keys.

I spent a lot of years choosing everyone else, bending myself into whatever shape made things easier for them. This time, I chose myself.

And you know what?

I sleep just fine at night.

The house is quiet. The doors are locked. The cameras blink steadily in the corners. My investments are where they should be. The little American flag magnet holds my plane ticket to Scotland on the fridge.

On the hook by the front door, my house key hangs alone, small and solid and mine.

That is not selfish.

That is survival.

If you are reading this and you are dealing with grown children who think they are entitled to your home, your money, your peace, hear me: document everything. Call a good lawyer. Get your health checked and keep the paperwork. Set your boundaries in ink, not in pencil.

Do not let anybody — not your son, not your daughter‑in‑law, not anyone — convince you that you owe them your life in exchange for their approval.

Because at the end of the day, you do not owe anyone your peace.

Not even family.

Maybe especially not family.

A week before my flight, the doorbell rang again.

I had gotten into the habit of checking the camera before answering. Old accountant brain: verify before you trust.

This time, it was my neighbor, Carla, from two houses down. Late fifties, always in a Seahawks hoodie, the kind of woman who brings pies to block parties and knows everybody’s business without being cruel about it.

She stood on the porch holding a small Tupperware container.

I opened the door.

‘Hey, Robert,’ she said. ‘Got extra lasagna. You want some?’

‘Lasagna is my love language,’ I said. ‘Come on in.’

She stepped inside, eyes flicking automatically over my shoulder, taking in the clean living room, the quiet.

‘You heading out somewhere?’ she asked, nodding at the open suitcase on the hallway bench.

‘Scotland,’ I said. ‘Three weeks.’

Her eyebrows went up.

‘Nice,’ she said. ‘Solo trip?’

‘Looks that way.’

She was quiet for a beat.

‘Good for you,’ she said finally. ‘We were all wondering if you were okay after the… situation.’

There it was again. That careful word.

‘I am fine,’ I said. ‘Better than fine, actually.’

She hesitated, then blurted, ‘My sister went through something like that with her kids. Not the glass part, but the “you have space, we have needs” part. She almost signed her condo over to them because they said it would “simplify” things. Lawyer talked her out of it. Best thing she ever did.’

‘Lawyers are having a good year,’ I said.

Carla laughed.

‘I will keep an eye on the place while you are gone,’ she said. ‘Bring in your mail. If your son shows up, you want me to call the cops?’

She said it lightly, but there was steel under it.

‘If he shows up with Britney, yes,’ I said. ‘If it is just him, tell him to go through my lawyer. You do not need to get in the middle.’

‘I am already in the middle,’ she said. ‘This is what happens when people argue on driveways. The whole neighborhood gets season tickets.’

I winced.

She shrugged.

‘For what it is worth,’ she said, ‘a lot of us think you did the right thing. My mom let my brother move into her basement “for a couple of months.” Took three years and a sheriff’s deputy to get him out. Boundaries are cheaper.’

She patted my arm, dropped the lasagna on the counter, and left me with that thought.

Boundaries are cheaper.

That night, I sat at the kitchen table with my passport, my itinerary, and a yellow legal pad. Old habits die hard; when my life feels big, I make lists.

On one side of the page, I wrote down everything I was leaving behind for three weeks: the house, the cameras, the locked file cabinet with my will and trust documents, the education accounts for the kids, the restraining order.

On the other side, I wrote down what I was choosing: cobblestone streets, cold air off the North Sea, bus tours with strangers, dinners where no one would tell me how to live my life.

The second column was longer.

Flying alone at sixty‑three is not the same as flying alone at thirty. Your knees complain louder, your back votes against middle seats, and you suddenly understand every older person who has ever stood up too early when the plane is still taxiing because their body just cannot take the angle anymore.

But there is something freeing about boarding a flight with no one asking, ‘Are you sure this is a good idea?’

I checked my house three times the morning I left.

Stove off. Windows locked. Cameras online. House key on the hook by the door. I stood there for a moment, looking at that small piece of metal.

For almost a year, the existence of that key had been an argument. Not out loud, but in every sideways comment, every suggestion about “safety” and “help” and “family.”

Give us a key, Dad. It is just in case. It is just so we can check on you. It is just so we can get in if you forget your phone.

Just, just, just.

Every just is a step toward not having a door to lock.

I left the key where it hung.

At the airport, I found my seat, buckled in, and watched Seattle shrink beneath the plane. The mountains rose up like silent witnesses. I thought of Sarah, of all the trips we had promised each other. Paris. New York. Scotland.

‘I am going,’ I whispered to the window. ‘I am finally going.’

In Edinburgh, I checked into a small guesthouse on a cobblestone street that looked exactly like every travel show I had ever seen. The room was small, the bed was firm, and the window looked out over slate roofs and chimneys.

There was a tiny American flag sticker on the suitcase of the man in the next room. Retired Army, it turned out. We nodded at each other in the hallway, two men of a certain age visiting a country our ancestors had only seen in history books.

The first few days, I did all the obvious tourist things. Edinburgh Castle. The Royal Mile. A bus tour with a recorded guide who cracked jokes about the weather and pointed out film locations.

Travel by yourself long enough and people either ignore you or adopt you.

On the second bus tour, a couple around my age from Ohio sat next to me.

‘You traveling alone?’ the woman asked.

‘Looks like it,’ I said.

‘Brave,’ she said. ‘I cannot even get my husband to go to Costco by himself.’

Her husband snorted.

‘She is the one who knows where everything is,’ he said.

We rode in comfortable silence for a while, watching stone buildings slide by.

‘We are here for our fortieth anniversary,’ the woman said. ‘What about you?’

I hesitated.

I could have said, Just a trip. Or, My wife always wanted to come. Both true, both incomplete.

Instead, I said, ‘I am celebrating doing something hard.’

‘Like climbing those castle steps?’ the husband asked.

I smiled.

‘Something like that,’ I said.

At a stop near a park, the bus let us off for twenty minutes. I walked a little apart from the group, found a bench, and watched a line of schoolchildren in bright vests march past behind a teacher holding a clipboard like a shield.

The kids’ accents made my chest ache.

I imagined Emma here, cheeks pink, taking pictures with her phone. Lucas rolling his eyes at all the “old buildings” and asking where the nearest burger place was.

For a flicker of a second, I saw Daniel too, standing with his hands in his pockets, making a face about the price of everything.

I pulled my thoughts back like a dog on a leash.

I had promised myself something when I booked this trip: that I would not let them come with me in my head.

Back at the guesthouse that evening, I checked my email.

One new message from Thompson.

All quiet on the home front. No contact attempts. Enjoy Scotland. Spend some money. Our friend in bank fraud says your son tried to call in and “check on balances.” They politely declined. System works.

I read the last line twice.

System works.

I pictured Daniel on hold with the bank, listening to tinny music and a recorded voice telling him how important his call was, only to be told he was not authorized.

A year ago, that idea would have made me sad.

Now, it just made me feel… safe.

On the fifth day, I took a train into the Highlands.

If you have never watched mountains slide past your window while you sip bad coffee out of a paper cup and listen to strangers talk about weather, I recommend it. There is something cleansing about being surrounded by people who know absolutely nothing about your life.

Across the aisle, an older woman with short white hair and a denim jacket embroidered with flowers was sketching in a small notebook.

‘You draw?’ I asked.

She smiled without looking up.

‘I try,’ she said. ‘Keeps my hands busy so I do not throttle my son.’

I laughed.

‘Universal theme,’ I said.

She glanced at me then, eyes sharp and amused.

‘You have kids?’

‘One,’ I said. ‘Son. And two grandkids.’

She made a small noise in her throat.

‘Lucky,’ she said.

‘He does not think so at the moment,’ I said.

She closed her notebook.

‘Family trouble?’

There is something about trains and strangers that loosens the tongue. Maybe it is the knowledge that you will never see them again. Maybe it is the gentle clacking rhythm under your feet.

‘I set a boundary,’ I said. ‘He did not like it.’

She nodded slowly.

‘They rarely do,’ she said. ‘What kind?’

‘He and his wife wanted her parents to move into my house,’ I said. ‘To “help.” When I said no, she threw a glass at my head. He tried to get into my bank accounts. I called the police. Got a restraining order. Have not seen my grandkids in months.’

I said it as calmly as if I were describing the weather.

The woman blinked.

‘Well, damn,’ she said. ‘You did not just set a boundary. You built a wall.’

‘I built a fence,’ I said. ‘With a gate I can open from my side.’

She smiled.

‘I like that,’ she said. ‘My name is Margaret.’

‘Robert,’ I said.

She stuck out her hand and shook mine firmly.

‘I kicked my daughter out of my house last year,’ she said casually. ‘She moved back in “for a bit” after a divorce. Brought the boyfriend with her. Suddenly my place was a flop house. I woke up one day and realized I was hiding in my own bedroom. Called a locksmith and a lawyer in the same afternoon.’

‘How is she now?’ I asked.

‘Angry,’ Margaret said. ‘But sober. Working. Paying her own rent. We talk on the phone sometimes. She is still mad I “chose myself,” as she puts it.’

She shrugged.

‘I told her, “I chose you for thirty‑five years. I get to choose me from here on out.” She did not like it. But she is still alive. That counts.’

We sat in comfortable silence for a while, watching green hills roll by.

‘People act like you stop being a person when you get past sixty,’ Margaret said finally. ‘Like your only job is to be grateful and available. You say no once and suddenly you are cold, or selfish, or ungrateful.’

Her words hit so close to home I almost laughed.

‘My son called me selfish,’ I said.

‘Mine called me dramatic,’ she said. ‘He is not wrong, but that is not the point.’

We both chuckled.

‘You did the right thing,’ she added.

‘You do not know me,’ I said.

‘I know the look,’ she replied. ‘You slept through the night for the first time in months after you made that call, didn’t you?’

I thought about the night after the restraining order was granted. The way I had fallen asleep without rehearsing imagined arguments in my head. The way the house had felt solid around me for the first time since the login attempt.

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘I did.’

‘Then you did the right thing,’ Margaret said.

At a small station where the train stopped for ten minutes, we got off and stretched our legs. The air was cold and clean, the kind of cold that wakes you up without slapping you.

Margaret lit a cigarette, took one drag, then ground it out.

‘Doctor will yell at me if he catches me,’ she said. ‘But sometimes I need to remember I still make my own choices.’

Back on the train, we swapped email addresses. Not because I expected a lifelong friendship, but because it felt right to have one more person in the world who knew the real version of my story.

After a week, Scotland started to feel less like a vacation and more like a mirror.

Everywhere I went, I saw small reflections of my life.

In a pub in Glasgow, a man my age argued loudly with his grown son about football. The son rolled his eyes, called his father old‑fashioned, then laughed and clapped him on the shoulder.

In a museum, a woman in her seventies pointed at a painting and said to the friend beside her, ‘My boys think I should sell my house and move in with them. Then what? Spend my days babysitting and cooking while they go to work? No, thank you.’

On a trail overlooking a loch, I passed a group of hikers in their twenties. One of them called to the others, ‘My mom keeps texting me, “You coming over Sunday? We need to talk about your dad’s will.” I am on a freaking mountain. Leave me alone for one day.’

Inheritance, expectations, the tug‑of‑war between independence and obligation — it is not uniquely American. It is human.

One night in Skye, I sat outside my small B&B, the sky a deep, endless blue that never quite went black. The owner, a quiet man with a thick accent and a dog that looked like it had seen everything, brought me a cup of tea.

‘You are very far from home,’ he said.

‘Feels closer than it did a few months ago,’ I said.

He cocked his head.

‘Family?’ he asked.

‘Something like that,’ I said.

‘Aye,’ he said. ‘They will take your roof if you let them. Best keep a hand on the keys.’

There it was again: the roof, the keys, the house.

On my last night in Scotland, I packed my suitcase with an efficiency that would have made Sarah proud. Socks rolled into shoes, shirts folded tight, small souvenirs wrapped in newspaper.

On top of everything, I placed Emma’s drawing.

I had brought it with me, tucked into a folder, like a small anchor.

It had gone from fridge to folder to suitcase without fanfare.

Sometimes the things that matter most are the ones we do not discuss with anyone.

On the flight home, I watched a movie with the sound off and thought about phase two.

Phase one, as Thompson and I had labeled it in that text from the ER, was simple: stop the immediate harm, document everything, lock down the assets, draw legal lines.

Phase two was trickier.

Phase two was learning to live without apologizing for the lines I had drawn.

Being back in my house after three weeks away felt a little like meeting an old friend in a new city. Familiar, but changed by distance.

The lawn was a little longer. Carla had brought in my mail and left a sticky note on the kitchen table.

No drama. Cat from next door sat on your porch for two days waiting for you. I told him you were on vacation, he did not care.

I smiled. There is something grounding about coming home to minor problems.

I walked through the rooms, touching walls, turning on lights.

My office. My bedroom. The guest room no one was moving into.

In the dining room, I paused.

The wall behind my chair had a faint discoloration where the wine had been. I had cleaned it, painted over it, but on certain days, in certain light, you could still see a slightly different shade.

A ghost stain.

I ran my fingers over it.

‘I remember,’ I said quietly.

In the months that followed, the world did what the world always does. It moved on.

News cycles changed. Neighbors found new gossip. Holidays came and went.

I spent Thanksgiving with a couple from my book club who refused to let me eat frozen turkey dinner alone. Christmas, I volunteered at a community center handing out gifts to kids who did not care that the man in the red sweater did not share their last name.

Each holiday that passed without my son at my table hurt a little less.

Pain has a half‑life.

In January, Emma’s trust statement arrived in the mail. Thin envelope, black and white numbers, official letterhead.

It listed the initial deposit, the modest interest, the schedule. Disbursement at twenty‑five for education, down payment on a home, or starting a business. A copy of the same statement for Lucas came a few days later.

I sat at the kitchen table with both of them laid out in front of me.

Here it was, in black and white: the promise I had made to myself and to them.

No matter what their parents did, the kids would get this.

Not because they were entitled to it, but because I chose to give it.

The difference between entitlement and a gift is who decides.

In February, I ran into Daniel.

Not at my door. Not on my lawn.

At the grocery store.

I was standing in front of the cereal aisle, debating between the brand Sarah used to buy and the one that tasted better but felt like cheating, when I heard his voice.

‘Dad?’

I turned.

He stood at the end of the aisle, a basket in his hand, surprise written all over his face.

For a second, we both froze like deer in headlights.

Then he walked toward me, slow, like I might bolt.

‘Hi,’ he said.

‘Hi,’ I replied.

He glanced at my cart.

‘You are back,’ he said.

‘I was not on Mars,’ I said. ‘Just Scotland.’

He half‑smiled.

‘How was it?’

‘Beautiful,’ I said. ‘Cold. Old. Honest.’

He swallowed.

‘Emma did a report on Scotland last month,’ he said. ‘She picked it because she heard you went there. She got an A.’

Something shifted in my chest.

‘Good for her,’ I said.

We stood in awkward silence for a beat.

‘Britney is not with you?’ I asked.

He shook his head.

‘No,’ he said. ‘She is at home with the kids. I am just grabbing milk.’

He looked older. More tired. Or maybe I was just seeing him without the filter of my own expectations.

‘How are you?’ he asked.

It was such a simple question, but for the first time in a long time, I believed he might actually want to know the answer.

‘I am okay,’ I said. ‘Better than okay, most days. How about you?’

He let out a breath that sounded like it had been stuck in his chest for months.

‘We are… managing,’ he said. ‘Counseling. Budgeting. Less DoorDash, more casseroles. Britney is still on probation. She… she wanted me to tell you that she is staying away like the order says. She is not going to show up at your door.’

‘That is good,’ I said.

He nodded.

‘Dad, I…’ He trailed off, then tried again. ‘I read the trust documents. The ones for the kids. The lawyer walked us through them.’

‘Okay,’ I said.

‘You did not have to do that,’ he said.

‘I know,’ I said.

He swallowed again.

‘I am angry,’ he said quietly. ‘At you, at her, at myself. Mostly myself. But I am also… grateful. For the kids. For what you did for them. And I hate that those two things live in the same place in my chest.’

‘Both can be true,’ I said.

He nodded.

‘I miss you,’ he said.

There it was.

I felt the familiar tug in my ribs, the one that said, This is your boy. Fix it. Make it easier. Let him off the hook so you can stop being the bad guy.

Old habits die hard.

‘I miss you too,’ I said.

We stood there between the Cheerios and the sugary stuff, two men with the same nose and the same stubborn line between their eyebrows.

‘I am not ready to have you back in my house,’ I said. ‘Not yet. Maybe not for a while. But I am willing to meet for coffee. Public place. No ambushes. No surprises.’

His eyes flicked up to mine, hopeful and wary all at once.

‘Really?’

‘Really,’ I said. ‘You can email Thompson. We will set it up. That way, everything stays clean.’

He nodded slowly.

‘Okay,’ he said. ‘Thank you.’

We parted ways at the end of the aisle.

At home, I put the groceries away, then sat at the table and stared at the wall for a long time.

I was not sure if I had just taken a step forward or opened a door I should have left shut.

But I had done it on my terms.

A week later, I sat across from Daniel at a coffee shop not far from my house.

We picked a table near the window. Neutral territory.

‘Ground rules,’ I said as soon as we sat down.

He almost smiled.

‘Of course,’ he said.

‘One,’ I said, holding up a finger. ‘We do not talk about me moving, selling the house, or anyone moving in with me.’

‘Okay,’ he said.

‘Two,’ I continued. ‘We do not talk about my will or my money, except to say that the trusts for the kids are not negotiable.’

‘Okay,’ he repeated.

‘Three,’ I said. ‘We tell the truth, even if it makes us look bad.’

He stared into his coffee.

‘Okay,’ he said softly.

So we talked.

We talked about his job, the constant pressure to hit numbers that were designed to be just out of reach. We talked about childcare, about how he and Britney had gotten used to a lifestyle their income could not sustain.

We talked about the night of Easter.

He did not excuse what Britney had done. He did not sugarcoat the login attempt. He admitted he had known what he was doing when he typed my security answers into that bank website.

‘I told myself it was just to check that you were okay,’ he said. ‘But I know that is not true. I wanted reassurance that there would be something left for us. For the kids.’

‘There will be,’ I said. ‘But not if you try to take it early.’

He nodded.

‘I heard “two million dollar house” and saw daycare bills and student loans and… I panicked,’ he said. ‘It felt unfair that you had all this space and we were drowning.’

‘Life is unfair,’ I said. ‘Sometimes in your favor, sometimes not. It is not a math problem you get to solve by taking someone else’s roof.’

He winced.

‘I know that now,’ he said.

We sat in silence for a while, listening to the hiss of the espresso machine.

‘When Emma sent that drawing,’ he said quietly, ‘I thought you would call. When you didn’t… I got so mad. I said some things to her I regret. I told her you did not care.’

It felt like someone had dropped a stone into my chest.

‘Do not put that on her,’ I said, sharper than I intended.

‘I know,’ he said quickly. ‘I told her I was wrong. Her therapist told us to let her feel how she feels without making promises we cannot control. So we told her, “Grandpa loves you, and when you are older, you can talk to him yourself.”’

That took some of the weight off.

‘Thank you,’ I said.

We talked until our coffee went cold.

When we stood to leave, he stuck out his hand.

‘Same time next month?’ he asked.

I thought about it.

‘We will see,’ I said. ‘One step at a time.’

On the walk home, I felt strangely light.

Not because everything was fixed — it was not — but because I had proof of something I had been afraid to test.

You can defend your boundaries and still leave room for grace.

That night, I stood in the doorway of the spare bedroom.

Sunlight from the streetlamp outside made a soft rectangle on the carpet.

A made bed. A small dresser. An empty closet.

Space.

I thought about all the ways that room could have been filled — with Britney’s parents’ suitcases, with tension, with whispered conversations about my “decline” — and all the ways it still could be used.

Sleepovers for grandkids, someday. A guest bed for a friend who needs a place to land for a weekend, not a year. An art studio if I ever get serious about those watercolor classes.

For now, it was just a quiet room in a quiet house.

Mine.

I turned off the light.

In the end, the story is not about the glass or the courtroom or the trust documents.

Those are just the sharp edges.

It is about a man who spent his life doing the responsible thing — working, providing, showing up — and finally realized that responsibility includes protecting himself from the people who think they are entitled to the fruits of that work.

It is about a house with a single key on a hook, a key that became a symbol of something bigger than a lock.

Control. Safety. Choice.

And it is about what happens when you stop apologizing for wanting all three.

Every morning now, I shuffle into the kitchen, make my coffee, and look at the fridge.

The American flag magnet holds up my Scotland itinerary, now marked with pen notes, and Emma’s drawing.

On the counter beside the sink, a small stack of legal envelopes sits, neatly filed and boring.

On the hook by the door, my house key hangs alone.

One day, I may hand that key to someone again.

Maybe to a contractor, if I decide to remodel. Maybe to Emma, when she is twenty‑five and has proven she understands the difference between a gift and a grab.

Maybe to no one.

That is the point.

I get to choose.

And after everything — the wine, the blood, the ER, the courtroom, the plane rides and coffee shop conversations — that simple fact is worth more than any number printed on a property appraisal.

If there is one number I keep in my head now, it is not the value of my house, or the balance in my accounts, or even the dollar amount sitting in those trust funds.

It is the number of nights I have slept with my doors locked and my conscience clear since Easter.

I stopped counting after a hundred.

Some debts you do not owe anyone.

Your peace is one of them.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load