The flag magnet on my mother’s stainless‑steel fridge was tilted forty‑five degrees, like even the little stars and stripes were bracing for impact. Sinatra rasped from a Bluetooth speaker someone had hidden behind the ceramic nativity, and the good linen napkins were folded into perfect triangles beside plates that looked more like props than dishes. My ultrasound print lay faceup on the end of the table, a glossy square catching the warm light from the pendant lamps. “You’re not a mother,” my mom said, her voice neat as the place settings. “You’re a walking mistake.” Tyler laughed. Greg didn’t say a word. I didn’t cry. I slid a thick manila folder across the runner, watched it skate past the salt cellar like a slow‑moving warning, and saw my mother’s face go pale the moment her fingers touched the brass fastener.

I had been quiet too long, and silence had started to sound like consent.

A week earlier I’d texted her the ultrasound—two little swirls, a heartbeat you could see but not hear. She’d replied, Be a normal daughter first, then become a mother. I typed a dozen responses and deleted every one. Then Marcus took my phone, set it face down, and said, “We’ll talk at Christmas.” We weren’t planning to go. We had movie tickets and a reservation at a Portland pizza place where no one knew my name, where basil plants lived on the windowsill and nobody corrected the way I breathed. But the folder sat on our kitchen table like an unanswered question, like a fire alarm under glass—Break in case of emergency. “We’re going,” I told Marcus. “I’m done being the understudy in a show that runs without me.” He nodded once and filled the car with gas.

The promise was simple: I would not let anyone narrate my life for me again—not in that house, not in any room with a U.S. flag tucked behind a plastic poinsettia and a script taped to the back of my chair.

When my mom opened the door on Christmas Day, she looked at us the way ushers glare when you slip into a theater mid‑scene. “I hope you’re not here to cause another scene,” she said, before hello. Marcus said, “Merry Christmas,” in the dry, respectful way he reserves for people who mistake control for love. I kept my coat on. The living room was identical to last year and the year before: candles in hurricane glass, a tree decorated like a catalog page, not a fingerprint on anything. Greg nodded at Marcus from the recliner and let his eyes slide over me like I was static. Some traditions have muscle memory. Tyler sprawled across the couch like he’d been born there, flicked his eyes over my stomach and snorted. “Wow. No shame, huh? Showing up like that after everything.”

“After what exactly?” Marcus asked, tone calm like a scalpel.

“Oh, don’t play dumb,” Tyler said, teenage even in his twenties. “The whole family knows how Claire acted. It was disgusting. Mom lost her mind from the stress. Now she’s pregnant by some random guy and thinks we should clap.”

“Tyler,” my mother snapped. “I asked you to behave.” She set a salad bowl down like a gavel. “Claire, this is Christmas, not your personal manifesto.”

I placed the folder on the table and rested my palm on it. “I didn’t come here asking for help,” I said. “This isn’t that.”

“Then what is it?” she said, already rolling her eyes toward the ceiling where the crown molding never stopped judging.

“It’s so you’ll look at me,” I said. “Not like a failed experiment that didn’t go according to plan.”

“We have always fought for you,” she said, spine straightening as if a teleprompter had lit. “You were difficult after your father died. We did everything by the book. And how did you repay us? With silence. With defiance. And now this pregnancy. Now this.”

“You make it sound like I stole your house,” I said.

“Don’t exaggerate,” she said, and her eyes flicked toward the folder as if it were a live animal. “What is that anyway? Another list of complaints?”

“You want to read it? Read it,” I said. “If not, don’t.”

We sat in the kind of silence where even a fork falling would register like a gunshot. Then she tugged the brass fastener. The first page was the independent psychiatric evaluation, ten pages with a raised seal, a date three months ago, language clear as a mountain sky: competent adult, no basis for guardianship, no evidence of the impairments once alleged. She scanned the first paragraph and lost all her color. Greg stood for the first time that evening and targeted Marcus instead of me. “If you put her up to this,” he said, “you should leave before it gets ugly.”

“I didn’t put her up to anything,” Marcus said, unblinking. “I’m standing next to her.”

The second page was a copy of my dad’s will. The third was the trust instrument with the clause he’d labored over in his last months: assets held for Claire until twenty‑five; no guardian or conservator to override; the house to pass to her outright; any attempt to divert funds to be considered a breach of fiduciary duty. My mother’s hand shook. She lifted a page, then another, and another. You didn’t, she whispered. You already filed this. “Merry Christmas,” I said. “Let’s step outside for some air.”

I’d spent years thinking oxygen was something you asked permission to take.

We stood on the back porch where the deck lights had been programmed to blink at exact intervals. The air tasted like cold pine and old arguments. “Are you sure they should read it alone?” Marcus asked.

“That’s the point,” I said. “No monologues drowning me out. Just facts louder than any voice.”

When I was eight my dad pressed my hand into wet cement near the back door and covered mine with his own, steadying the push until my little palm left a crooked print next to his larger one. He said, “This is your house, even when I’m gone. I promise.” After he died, the house stayed quiet, but not with grief. Grief is loud. This quiet was administrative. My mother turned motherhood into a project plan. Greg moved in. Tyler arrived. I became a task to be accomplished, then set aside.

At fourteen they took me to family therapy. The word used was “unstable,” a soft label with hard edges. Guardianship followed, official and tidy: signatures, seals, words that sound like care and work like a cage. I couldn’t sign a lease, open a bank account, or consent to a field trip without written approval. “You know how you get,” she would say. “This is for your own good.” She called every attempt to speak a symptom; every page I wrote was attention‑seeking; every song I loved was proof I was too much. The only person who had ever looked at me and seen a person had been gone for six years.

Then there was Marcus, and the first thing he did was listen without looking for a screw to tighten.

“Nice facade,” he said now, leaning against the railing, gaze on the glass doors. “No air inside.”

From the kitchen came a muted rhythm as pages shuffled. A minute later Tyler filled the doorway with his performance face—a mix of pity and superiority. “You actually did it,” he said.

“You thought I wouldn’t?”

“Mom’s freaking out,” he muttered. “Says you ruined everything. Says we might lose it all.”

“We,” I repeated. “Tyler, you’ve been living off my money for years. You drove my car. Your tuition came from my trust. But now it’s ‘we’?”

“I thought it was family,” he said, but the word didn’t look right in his mouth.

Hurt used to live in my chest like a tenant with a lifetime lease; now it was packing.

We went back inside. My mother stood by the fireplace, one hand hovering over the folder as if it might explode. Greg sat like furniture. “This isn’t real,” she said, voice shaking but still rehearsed. “This is fake.”

“The documents are signed,” I said. “The evaluation is independent, the court has received the petition, and the audit request is pending.”

“How did you even—how did you know about the will?” she snapped. “You were never smart enough to—”

“Dad kept copies in two places,” I said. “One with his lawyer, one in a bank safe. I had legal access at twenty even under guardianship.”

The hinge sentence was simple and it belonged to me: I was done asking for permission to be the person my father knew I already was.

She flipped to the ledger Marcus had compiled—line items, dates, check numbers, amounts, the kind of math you can’t argue with. $19,500 to Westhaven Renovations. $7,000 to “Elite Prep Tutoring” the month Tyler’s SAT score magically bloomed. $4,280 to “Marigold Travel” the same week their Bahamian photos appeared. $1,100 withdrawn as cash on a Tuesday when I’d asked for bus fare and been told there was “nothing left.”

Greg reached for the folder and I tugged it back. “The copies are already filed,” I said. “This is just your reading copy.”

“You don’t understand what this could mean,” he said. “If a court—if a court—”

“Rules according to the documents,” I said, “then the guardianship ends, the audits proceed, and any misused funds will be addressed.”

“You’re destroying this family,” my mother whispered, more breath than voice.

“No,” I said, and even my hands were steady. “I’m leaving it before it destroys me.”

We left without drama. The cold air outside felt clean, and for once I wasn’t afraid to breathe it.

In the five days that followed there were twenty‑nine missed calls, fourteen texts from numbers I didn’t recognize, three DMs from people I hadn’t spoken to in years, and one Facebook post that didn’t use my name but did use every detail necessary for anyone to know it was me. Aunt Linda dialed from an Arizona area code and asked if I was “really doing this to your mother.” My old manager called because HR had received an “informational concern” from a “family member.” It’s just a formality, the HR woman said kindly; could I talk to someone from the EAP? I laughed until I cried, then scheduled the call, answered every question, and got an email that used words like appropriate and no further action.

It is wild how fast old narratives try to reclaim your name when you stop letting them borrow it.

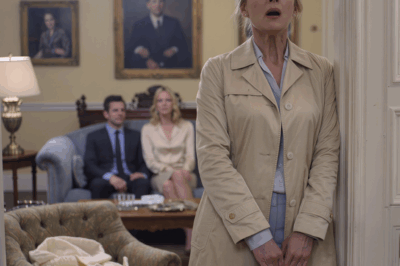

Two evenings after the EAP call the doorbell rang. My mother stood on the step with Greg half a pace behind. She held a wrapped bundle like a gift. “We want to talk,” she said. “As a family.”

“You already held your family meeting on Facebook,” I said. “You have two minutes. On the porch.”

“You don’t understand where this is headed,” Greg said. “You’ve started something you can’t finish. We have connections. We can stop this or make it—”

“Worse?” Marcus stepped into the doorway and lifted his phone. “If you don’t leave, we call the police.”

They didn’t move. My mother leaned in. “You’ll think this over,” she whispered. “You know you can’t do this alone.”

Two days later the countersuit arrived by certified mail: Petition to declare me partially incapacitated for the duration of the legal process; allegations of undue influence; references to unspecified “incidents.” The letterhead was expensive. The content was empty. But noise is still noise when you’re trying to sleep. At our dining table—pine, thrifted, carved with tiny dents from other people’s lives—Marcus laid out what he called The Case: the evaluation, the original will, the trust terms, emails, a letter my mother had sent a bank with a signature that wasn’t mine, audio recordings of calls where she insisted I was “not safe to make decisions.” He compiled it, paginated it, tabbed it in blue, and mailed it like a passport.

“None of this is magic,” he said. “It’s just the way out.”

The hearing was set for late February, 10:00 a.m., Courtroom 5B of the Multnomah County Courthouse. We stood in front of the building where two flags lifted—Oregon’s blue and the U.S. flag flaring in wind that smelled like the river—and I realized I wasn’t scared. Just ready. I wore a plain gray dress and a coat that had seen better winters. No makeup. No jewelry. I wanted no one to mistake aesthetics for truth. The judge was a woman in her fifties with a voice that could stop a swing mid‑arc. She kept bringing everyone back to facts, the way a good teacher returns a class to the problem on the board.

Their lawyer tried “messy family matter,” tried “emotional instability,” tried “we only want what’s best.” Ours said, “Here are the documents.” The court‑appointed psychologist spoke exactly three sentences from her report: fully competent, no clinical basis for guardianship, and any continued constraints likely to cause harm. My mother stared across the aisle like I was a stranger who had broken into her narrative. Greg sat with his jaw tight, an expression that said he still believed there was a trapdoor they could pull.

The hinge sentence in the courtroom was the judge’s: “Guardianship is terminated, effective immediately.”

Paperwork moved; seals pressed; copies stamped. The bailiff said, “Next case,” and just like that, the cage I’d been told was for my own good dissolved into a file folder someone would shelve.

A week later an order went out authorizing an audit of the trust accounts for the years of the guardianship. The numbers didn’t just speak; they shouted with microphones. $118,400 in tuition payments for a son who wasn’t me. $42,600 in “household upgrades” that corresponded exactly with pictures of a kitchen remodel my mother had posted. $9,750 in “medical travel” the same month they’d posed with drinks under a thatched roof in Nassau. $3,200 in cash withdrawals that never landed anywhere I could eat, ride, or read. The accountant’s phrase was clean and merciless: breach of fiduciary duty.

We filed a separate claim for financial exploitation. The court ordered repayment of misused funds plus penalties plus my legal costs. That’s when we learned the truth behind the truth: they didn’t have it. The house they’d treated like theirs had been used as collateral, refinanced, and dressed up with ribbons of debt. On paper it still belonged to me. When the guardianship ended, legal control returned with a flat, unimpressed thunk. Marcus and I hired a property specialist whose face did not change as she flipped through the stack and said, “We can reclaim. We can sell. We can close the chapter.”

“How much will be left?” I asked.

“Enough to pay for a life you choose,” she said. “Not a life managed for you.”

Every three to four hundred words, the same sentence returned to me in different clothes: I would not move back into a cage just because someone had hung Christmas lights across the bars.

Tyler wrote a letter on college‑ruled paper like it was 1997. No apology. Just grievance. You destroyed this family. You chose a stranger over us. No sane person will stand by you. I put the letter in a banker’s box with tabs that read Audit, Court, House, Letters. I didn’t keep it for sentiment. I kept it to remember that I had survived the part where people say you’re unloving for not setting yourself on fire to keep them warm.

My mother and Greg divorced. He moved into a month‑to‑month rental behind a strip mall; she moved into an apartment with laminate floors that looked like wood on a cloudy day. I didn’t check on them. Other people did and relayed updates I hadn’t asked for. A few relatives called, a few apologized, and a few said nothing and meant it. I answered some. I let others ring out. My lungs had only so much room and I had promised myself oxygen.

We sold the house in March. The closing papers weighed exactly as much as the folder I had slid across the table in December. I went back one last time with a notary, a locksmith, Marcus, and a pair of gloves because memories have dust. We walked through rooms staged to look like welcome and I pulled the picture of me and Dad off the mantel. I could hear my mother’s voice in my head—Don’t ruin the wall, Claire—and I smiled because the only thing I ruined was a script. On the way out I stopped at the back door where the cement squares had weathered to a faint speckle. I knelt and traced a finger through the crooked little print that matched my hand. “You kept your promise,” I told the air. “I finally kept mine.”

The payoff wasn’t fireworks. It was lasagna reheated at 9:15 p.m. while we watched a Blazers game with the sound off because my head needed quiet. It was a basil plant in a chipped mug in a rental on the edge of Portland where the MAX line hums like a lullaby. It was an ultrasound photo tucked into the corner of a picture frame so the baby’s future could sit next to the past without anyone trying to control the conversation. And it was me breathing, slow and steady, in a room where no one wanted me to prove I deserved to inhale.

“Do you want a flag pin for the hearing file?” Marcus joked one night, to make me smile. He’d found a tiny U.S. flag sticker in a drawer. I stuck it on the back cover of the copy we kept at home, a private note to a country that had tried, through a handful of people, to parent me with paperwork.

The last thing my mother sent was a postcard of a beach, the kind you buy at a gas station off I‑10, a sky so blue the ink felt shy. On the back she wrote, You will regret this when he leaves you. People like him don’t stay. She never wrote Marcus’s name. She didn’t have to. I slipped the postcard under the elastic band around the banker’s box and decided that some sentences don’t require an answer; they require a life that proves them wrong.

On a Saturday in May we drove out past Troutdale to the river. The air smelled like clean metal and the color green. Families grilled under park shelters; a kid in a Mariners cap tried to fly a kite and failed forward with joy. An older couple waved as we passed; the woman had a tiny flag stuck into the sleeve of her folding chair. We set a blanket on the grass and I lay down with my head on Marcus’s thigh. “Do you ever wish you could go back and rewrite it?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “I only wish I’d used fewer commas and more periods.”

He laughed, soft. “Hard stops are underrated.”

That night the baby kicked for the first time, a small tap like a knuckle on a door. I put Marcus’s hand where I’d felt it and we both stared, as if our looking could make the movement happen again. It didn’t. Babies don’t perform on cue. They live. I cried a little, quiet tears, the kind that come when something inside you believes you are allowed.

There were costs, of course. The audit didn’t refill the account. The sale paid debts that weren’t mine, and the remainder looked less impressive once it was finally, totally mine. People will tell you that winning feels like a parade. Sometimes it feels like a decent checking balance and a night where your phone doesn’t light up at 2:07 a.m. Sometimes it feels like knowing who holds your spare key. We chose to spend our money on boring things: health insurance, a crib that would outlast a growth spurt, a plumber named Randy who fixed a pipe that sounded like it was swallowing ghosts. We gave $500 to the legal clinic where Marcus volunteers on Thursdays because the world doesn’t correct itself politely.

My job stabilized. Remote work suited a person who had spent a decade having her choices second‑guessed. I taught two online sections of a media literacy course and wrote occasional articles under my name. I signed contracts with my hand shaking only a little. When the W‑9 forms arrived, I filled them out without the old creeping dread that someone would tell me I had gotten my own name wrong.

Sometimes, on purpose, I walk past a courthouse. I like seeing flags outside against the sky. I like seeing people in coats moving toward doors they chose to walk through. It reminds me that paperwork can be a cage, but it can also be a key when you stop letting other people hold it.

One afternoon in June I got a text from a former neighbor: Your mom stopped by your old house. She stood in the street and stared. I should have felt something large. Instead I felt a small sympathy for anyone still worshiping at a place that had stopped being sacred. I sent the neighbor a thumbs‑up and then watered the basil, because living things require attention.

I won’t pretend there aren’t nights when the old script tries to understudy the new one. There are, and on those nights I put my palm against the belly where our baby sleeps and say out loud, “You are not their project. You are not mine, either. You are a person.” Then I tell myself the same thing, because learned care is a practice and not a trophy.

The last time I drove past the old block the porch still had the wreath my mother insisted on hanging every year—a thick circle of plastic holly that pretended to be evergreen. A realtor’s sign leaned a little, weather taking small bites from the edges. In the window I could see the faint outline where the photo of me and Dad had hung. The space looked like the breath you take when the story finally stops asking you to perform it.

I parked a block away and walked with Marcus to the back alley where the slabs of cement waited, sun warming surface into a heat I could feel through my jeans. I pressed my hand down again, this time not in wet cement but on the old imprint, adult palm against childhood shape. Then Marcus pressed his hand next to mine and smiled. “Someday,” he said, “we’ll bring our kid here. Not to worship. To witness.”

“Someday,” I agreed.

I used to think a payoff had to be dramatic. Now I know it can be as ordinary as a quiet kitchen where the only agenda is dinner, a kid’s drawing stuck to the fridge with a crooked flag magnet, and a life where the loudest thing is laughter that doesn’t ask permission. The folder that began all of this lives on the top shelf of our closet in a fireproof bag. Not because I’m braced for another emergency. Because sometimes the proof you need now is the proof that saved you then, and it’s good to know where you put it.

There’s one more sentence I keep for hinge moments, a plain sentence with a spine: I am not their property.

When the baby is born in late August, I’ll bring a small brass frame to the hospital and slide two photos behind the glass—one black‑and‑white of a handprint in concrete next to a bigger hand, and one grainy ultrasound where a shadow looks like a comet learning to become a person. A nurse will bring a form. I will fill it out, no one standing over my shoulder with a red pen. The flag in the corner of the room will hang still in the recycled air, not as a symbol of perfection but of the right to stand up, tell the truth, and sign your own name. And if anyone ever asks me what changed on that Christmas night, I’ll say: nothing, except everything. I slid a folder across a table and chose a life that didn’t require an apology to begin.

Summer didn’t arrive like a season. It arrived like relief. The court’s orders turned from PDFs into calendar entries, and the flurry of messages from people who knew me well enough to ask for the truth settled into a manageable trickle. We switched to decaf after noon. We learned our neighbors’ names. The basil doubled. One afternoon I found a tiny flag magnet at a thrift store, the kind that used to live on my mother’s fridge. I bought it for fifty cents and stuck it on ours, slightly crooked on purpose. Every time I reached for milk, I saw the stars and stripes leaning left and felt my spine lean steady right.

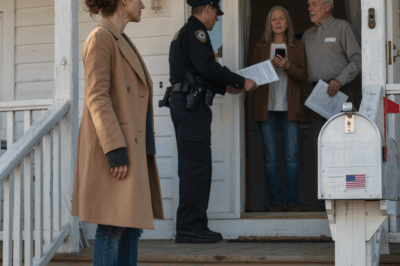

Three weeks after the hearing a police cruiser rolled up to the curb outside our rental, lights off, engine idling. Two knocks, firm and measured. Marcus opened the door because my chest had learned enough pounding for one life. The officer’s nameplate read Collins. He was middle‑aged, practiced kind eyes, the kind of presence that tells you he’s fielded a hundred different versions of the same human weather.

“Evening,” he said. “We received a welfare call. Anonymous.”

“Of course you did,” I said.

“We’re not here to escalate,” he added quickly. “We’re just checking. Someone said you might be in distress.”

“I’m pregnant and watching reruns,” I said. “My distress is that our lasagna is on the edge of dry.”

He almost smiled. “Can we come in?”

Marcus looked at me. I nodded. We showed him the living room with books and a couch that had opinions about posture, the kitchen where a pot bubbled, the folder sitting on a shelf like a small quiet thundercloud. I handed him a copy of the order terminating guardianship because I had learned to keep duplicates the way some people keep umbrellas by the door.

“Thank you,” he said, reading the header. “This happens sometimes.”

“I know,” I said. “It’s exhausting anyway.”

“If more calls come in, document the dates,” he said. “If anyone shows up uninvited and refuses to leave, 911. Otherwise, try to have a good night.”

When he left, I wrote the time on a sticky note: 7:42 p.m. Two minutes later, I stuck it under the elastic on the folder. I wasn’t pinning butterflies. I was pinning noise.

I had once believed that peace would feel like nothing happening. But peace, it turned out, felt like ordinary things happening on my terms.

The post‑judgment process moved like a careful machine. A hearing for restitution calculations. A motion about interest. A clerk who stamped documents with a rhythm you could dance to if you were patient enough. Greg sat with a new lawyer and the expression of a man who had mistaken charm for strategy his entire life. My mother tried silence as a tactic and discovered it reads like consent when the other side has receipts.

In July a notice arrived for a judgment debtor exam. The language was dry; the stakes weren’t. Marcus prepped me the night before as if I were the one on the stand, not because I had to testify, but because he understands I sleep better when I know where the doors are.

In the exam room, a court reporter typed in a steady clatter that reminded me of rain. Greg answered questions in sentences that moved like cheap furniture over tile. “I don’t recall.” “That was my understanding.” “We believed it was for household needs.” Marcus slid a photocopy across the table—Elite Prep Tutoring, invoice, $7,000 paid in two transfers, dates bracketing Tyler’s miraculous SAT bloom. Then the kitchen remodel contract: $42,600. Then the travel agency receipt: $9,750. Numbers don’t need adjectives when they show up dressed as themselves.

Greg reached for a half‑smile he’d used successfully in other rooms and discovered it had expired. “We were under the impression—”

“That guardianship gave you spending authority,” Marcus finished for him, calm as ever. “It did not.” He tapped the trust clause with a pen. “You were not a trustee. You were a beneficiary of a household you did not fund.”

The court reporter caught the tap in parentheses: (taps document). It read like punctuation. It was.

On the way out, I realized I wasn’t shaking. I bought a soda from the machine in the hallway and drank half of it, cold and too sweet. Marcus laughed when he saw my face. “You look like a kid who just tried root beer for the first time.”

“I hate root beer,” I said. “But I love this.”

I used to think closure was a locked door. Now I know it’s a door you can open and close without asking who hid the key.

People talk. It’s what they do when the story in their head hits a wall with a sign that says Nope. There were quiet consequences after the exam. Tyler’s girlfriend unfollowed my mother, then posted cupcakes with blue and pink sprinkles that looked suspiciously like a baby shower not attended by the woman who named me difficult. Aunt Linda called again, this time not to deliver my mother’s script but to apologize for reciting it earlier. “I should have asked you first,” she said. “I’m sorry.” I said, “Thank you.” Because sometimes thank you is the exact size of forgiveness.

We kept our world small. We bought a stroller from a neighbor two doors down who had twins and a garage full of hope that turned into reality faster than they’d planned. We found a pediatrician whose waiting room smelled like lemon and sanity. We looked at cribs and left the store laughing because we couldn’t pick between the one with the soft corners and the one with the better screws. Marcus said, “Let’s get the one that will survive a toddler with opinions.” We did.

On a Wednesday in late July, HR pinged me with a new contract for the fall term. “We like the student comments,” my department chair wrote. “Clear. Kind. No fluff.” I printed the email and slid it under the same elastic as the sticky note from Officer Collins’s visit. The folder wasn’t just evidence against what had been done. It was evidence for what I could do.

The hinge sentence kept showing up like a friend who doesn’t knock: I will not live inside their version of me.

August arrived with heat that stuck to your back and a calendar full of practical circles. Week 37. Week 38. We packed a hospital bag with snacks and chargers and a brass frame for the photos I had promised myself I would bring. I put the folder in the hall closet and then took it out again because superstition is just the nervous system asking for a job. I put it back with a pat like it was a pet learning to stay.

Labor started on a Tuesday night at 11:17 p.m., a time my mother would have called inconvenient as if bodies carry day planners. Marcus drove us to the hospital with both hands on the wheel and Sinatra whispering from the radio because somehow he knew it would make me laugh. A nurse with a flag pin on her scrubs checked me in. “Deep breaths,” she said, and I smiled because for once the instruction didn’t feel like a scold.

The ER lights were too bright but the people under them were kind. The hours folded. A resident introduced herself, a doctor with gentle hands did the necessary, a lullaby of beeps kept rhythm. In the corner, the brass frame waited with the handprint photo and the ultrasound tucked behind it like a secret that wanted to be made public. I gripped Marcus’s hand and then the rail and then the moment itself as if it were something you could hold. At 6:02 a.m., our son arrived with a cry like a question finally answered.

“Hi,” I said, the smallest word doing the largest job. He was warm and he was heavy and his fist opened like he’d been holding a key and finally wanted to show it to us. Marcus cried, quiet tears that ran straight down without detouring. The nurse laughed softly. “You two okay?”

“We’re good,” I said, and felt the truth of it settle in my bones like a chair that knows you.

They moved us to a room where the blinds lifted to a sky so blue it felt edited. The flag on the pole outside hung still for a long time and then fluttered once, like a nod. I slid the two photos into the frame and set it next to the bed. My dad’s hand and mine. The ultrasound that had started a war my mother thought she could win with volume. And now this—proof that life doesn’t need permission slips.

We named him Ezra because Marcus liked the way the Z insisted on being heard without shouting. My phone buzzed exactly twice that day: a text from Aunt Linda with a string of heart emojis that made me forgive every misstep she’d made out of loyalty to the wrong person, and an email from the court with a stamped copy of the final order on the financial case. Repayment schedule approved. Penalties affirmed. Motion to reconsider denied.

I didn’t forward the order to anyone. The only people who needed to see it were asleep in the room—one in a bassinet, one in a chair that had learned to recline at last.

The first week home tasted like pancakes and caution. We slept in ninety‑minute pieces. Marcus did laundry at 3:14 a.m. because tiny socks refuse to respect daylight. I learned the geometry of a swaddle and the art of the one‑handed sandwich. We took Ezra to his first pediatric visit, where a nurse measured his head with infinite seriousness and wrote down numbers that felt like a future. On the fridge, the crooked flag magnet held up his appointment card. I laughed at the symmetry and took a picture that no one else needed to see.

Three days later, a knock. Not the measured kind. The familiar staccato of someone trying to own a door by beating it. I looked through the peephole. My mother stood there alone, hair neat, expression neater. In her hands she held a white box with a silver ribbon—department store neutrality. I opened the door but kept the chain. “We’re not receiving visitors,” I said.

“I’m your mother,” she said, as if nouns were keys.

“You’re the woman who made a public case about my private life,” I said. “What do you want?”

“I want to meet my grandson.”

“Not today,” I said. “Maybe not ever.”

“That’s cruel,” she said. “You can’t keep him from me.”

“I can keep my home safe,” I said. “And I can keep my son safe from people who confuse control with love.”

She lifted the box. “It’s a gift.”

“For who?”

“For the baby.”

“What is it?”

“A christening outfit,” she said. “He should be presented properly.”

“We’re not presenting him,” I said. “We’re raising him.”

Her face did the thing it does when a script goes missing. “You think you’ve won,” she said softly.

“I think I’m free,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

“Greg left,” she blurted quietly, as if it were a credential. “He said I ruined everything. I never thought—” She stopped. The silence was almost a confession. Then the old tone returned, brittle and bright. “You’ll regret this.”

“I regret not choosing myself sooner,” I said.

I closed the door. Ezra stirred, then settled, then breathed that deep baby breath that forgives a thousand drafts of the same bad sentence. I leaned against the wood for a minute because boundaries take energy even when they’re right. Marcus appeared with coffee that tasted like a small miracle. “You okay?” he asked.

“I am,” I said, and surprised myself with how much I meant it.

There were more ripples. Tyler posted a sixty‑second video about loyalty that earned three comments and two pity likes. An older cousin sent a group text that said Family First, to which a braver cousin replied, Not at the expense of an actual person. The family group chat changed its name from “Home Base” to “Cousins and Chaos,” which served as an accidental thesis for the year. A check arrived from Greg’s attorney that covered one monthly payment under the order and then stopped arriving. Our lawyer filed a motion. The court set a compliance hearing. The machine moved.

In early October, I took Ezra to the park by the river where we’d picnicked in May. The air smelled like leaves considering their next move. A woman with a Yankees cap smiled at us and asked how old he was. “Seven weeks,” I said, and felt the number bloom into something bigger than math. Near the water a kid planted a tiny stick flag next to a sand castle and saluted, serious as a judge. Ezra slept in the sling against my chest, warm and borrowing my heartbeat like a metronome.

I’ve started to understand that the story I inherited was not a legacy but a script. Scripts can be edited. Legacies can be rewritten in the present tense.

The compliance hearing happened over Zoom because the world discovered you can do almost anything in a rectangle if you have to. Greg showed up with a blurry background and the look of a man negotiating with both the court and his own mirror. My mother did not appear. The judge did not care. Orders are orders whether you attend the scene or not. A new schedule. A threat of wage garnishment that wasn’t a threat so much as a map.

That night, after we put Ezra down, I took the box from the closet, the one with the folder and the sticky notes and the postcards people sent when they couldn’t say sorry out loud. I added a new tab labeled Ezra and slipped his hospital bracelet inside. I held the handprint photo, the ultrasound, the termination order, the audit summary, the repayment schedule, the HR email about my class, the pediatric appointment card with a star next to 10:30 a.m. It looked like chaos. It was a portrait.

The hinge sentence had one last job: I am building a life that does not require me to shrink to fit in the frame.

In November, the rain settled in like a friend who knows where the mugs live. We learned the art of baby coats and booties you can’t lose because they loop. We cooked a turkey breast instead of a turkey because the only guests we invited were sleep and quiet. On Thanksgiving, Marcus lifted Ezra and said grace the way he does, concise and true: “Thanks for enough.” We ate at the coffee table and watched a parade we turned off twice when the commercials got too loud.

December came back around with lights we chose because they looked like stars not because they matched a theme. I mailed exactly three cards: one to Aunt Linda with a picture of Ezra’s hand curled around my finger; one to the legal clinic with a donation; and one addressed to myself, which sounds ridiculous until you’ve needed proof from your own pen. Inside I wrote: Dear Claire, you did it. Not fireworks. Not perfection. Just the quiet courage of hard stops and a crooked flag magnet on a fridge that belongs to you.

On Christmas Day, we drove past the old block once because I wanted to see what memory looked like in winter. The house had a wreath that didn’t belong to us anymore and a For Sale sign with a sticker that read SOLD. A new car in the driveway. A plastic snowman waving at no one in particular. I didn’t feel triumph. I didn’t feel ache. I felt the way you feel when you finally take off a pair of shoes a size too small and realize you had toes the whole time.

“Do you want to stop?” Marcus asked.

“No,” I said. “I want to go home.”

We drove to our rental where the crooked flag magnet held up a drawing I’d made with Ezra’s help: a smear of blue and red that looked like weather having a good day. I heated lasagna because some victories are a meal reheated on purpose. Marcus set the table. I slid the folder down from the top shelf and placed it next to the salt. Ezra slept. Sinatra hummed from the speaker because some callbacks are earned.

I opened the folder for a second—not to measure the past, but to admire the spine of a story that refused to break. Then I closed it and put it away.

If someone asked me what changed since last Christmas, I would say: I stopped auditioning for a role I never wanted. I wrote my own stage directions. I let the facts be louder than the performances. I made peace with simple sentences. I let a life begin that had nothing to do with being anyone’s lesson.

I am not their property. I am a mother. And when I slide a folder across a table now, it’s full of printouts of pediatric tips and a recipe for lasagna that works every single time.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load