My father’s voice ricocheted off the knotty pine walls of the Bear Lake living room, rattling the picture frames and the ceramic trout above the fireplace. “How could you be so selfish?” he shouted, pacing, bare feet slapping the old hardwood as if he could stomp me into agreement. My mother sat with her hands folded, eyes pinned to her lap. Outside the window, the water lay cold and polished, a sheet of blue glass. Inside, a property tax bill waited on the coffee table like a loaded pistol aimed at my future.

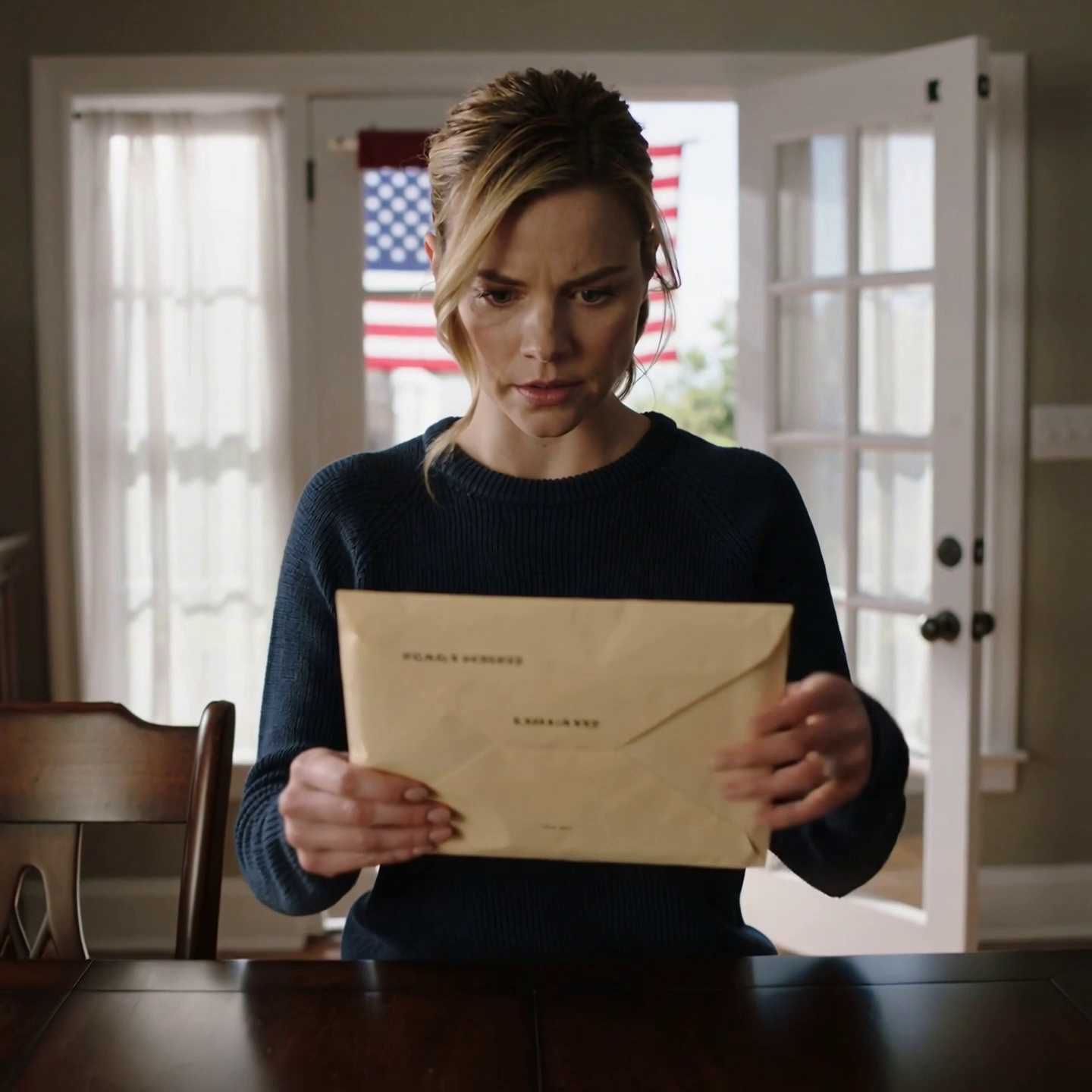

I kept my palm on the envelope I’d brought inside, the one my father had pushed toward me with an air of choreographed surprise, as if the bill had wandered in of its own accord. The paper was thin and municipal, the numbers printed with the indifference of government. I’d paid this same bill five years running—quietly, reliably—because I was the daughter who didn’t need help, the daughter who “understood the value of money.” I had believed those lines the way children believe in constellations: connect the bright points and call it meaning.

“You know your sister needs capital for the new business,” he said, voice softening into the reasonableness that had always trapped me better than rage. “You’ve got more than enough, Louise. It’s time to pull your weight again.”

I realized then that what I had been doing all these years—writing checks for taxes, for Megan’s late car payments, for my mother’s physical therapy when insurance ran dry—had never been considered generosity. In my father’s vocabulary, it was duty. A pipeline. A gravity-fed stream.

“Dad, I’ve been paying for everything,” I said. My voice steadied even as the back of my neck prickled. “The property taxes. Megan’s business trips. Mom’s medical bills. Five years of this. I can’t keep doing it forever.”

My mother did not look up. The clock over the mantel ticked. Somewhere down the hill a snowblower coughed to life. The world outside went on with its errands while mine stopped.

He lifted his chin at the bill, then turned as if the logistics bored him. That’s when I saw the corner of another envelope sticking from beneath a boating magazine, the black serif capitals of a law firm whispering through the paper: TRUST FUND. Megan Walsh.

It wasn’t a decision. It was muscle memory. I reached for it. His hand snapped out, too slow. “Louise—that’s private.”

The pages slid into my fingers with the slippery weight of an eel. I scanned them, my pulse beating in my ears. Numbers swam: three hundred fifty thousand dollars. Additional provisions. Future contributions.

For Megan. Only Megan.

My father had told me there “wasn’t enough” when I begged for help with tuition. Not out of cruelty, I’d told myself, but out of scarcity. He’d said we all tightened our belts after the 2008 hit to his construction supply business. He’d told me the family had to pull together. It had sounded like a sermon; I tried to be a good congregant. I drank thin coffee on the night shift and learned to day trade in the two-hour slivers between classes and work. I built a life from charts and candlesticks and a gut trained to hear the market breathe.

And meanwhile, this. The money that didn’t exist had existed. It had simply been earmarked for the daughter who never had to learn the word “enough.”

“When were you going to tell me?” I asked. The words came cool and even, the way snow falls. The way a new truth settles over an old story.

“You weren’t supposed to see that,” he muttered, and for a second I glimpsed past the posture to the smallness underneath. He folded the document and slid it back into its envelope as if folding the reality would reduce it.

“I guess that explains the student loans,” I said. “Explains why the answer was never no, it was not now.” A dozen chafed memories rose, then fell; I pushed them back beneath the surface where they’d lived for years, smoothed and rationalized. “You created security for Megan while I became your safety net.”

“That’s not fair,” he shot back. “We gave you everything growing up. And you—” he gestured vaguely at my life “—you can handle yourself, Louise. You’re the one who made it. Your sister needs help to get started.”

Twisted logic, gilded with pride. You’re so capable that we will always ask more. We will call it love. We will forget to say thank you.

I felt the floor tilt and then right itself beneath me. The lake caught a moan of wind. I slid the property tax bill toward me and measured the decision that arrived like a tide.

“I’ll take care of it,” I said. His shoulders dropped, relief smoothing his jawline. He did not look for the second decision crystallizing in me—one that would not be spoken aloud in his house.

On the drive back to Salt Lake City I watched the Wasatch darken to charcoal ribs under a sky the color of bruised plums. Semis shouldered past, their taillights a red Morse code. The mountains have always steadied me; that night they seemed to loom like judges. When I reached my apartment, I ignored my phone’s glow—his name pulsing on the screen, my sister’s, too—and opened my laptop.

The spreadsheet waited in a folder labeled with a lie I’d told myself: FAMILY MISC. I’d been meticulous because day trading rewards meticulousness and punishes myth. The tabs were neat and damning. Property taxes, Bear Lake: $8,700 per year for five consecutive years. Megan’s car payments during her bad quarter that stretched into twelve: $11,680. New roof and structural repair after the windstorm: a figure that still made my chest tighten when I typed it, notes attached—contractor receipts and photos of shingles like black waves: paid by me. Knee surgery co-pays and out-of-network specialist visits for Mom when the pain was worst: $12,000 and change. Three family vacations under the generous label of “my treat,” numbers that had once felt like love and now looked like tuition I’d paid to an old belief.

The total rose as I scrolled; the number turned round and brutal. Six figures. I thought of the positions I might have held, the compounded returns forfeited. I thought of the nights I watched futures charts like a heartbeat and held my breath as a trade grazed a stop. I felt stupid and then I felt something else: clean.

The next morning I drove to the granite building on Main where Joseph Klein kept his office. Joseph had been careful with me back when my profits first outpaced my wisdom. He’d taught me to diversify when I wanted to sprint, to tax-loss harvest when I wanted to look away, to think in decades around a profession that lives minute to minute.

“This is quite a ledger,” he said now, flipping through the pages I’d printed and arranged. “You’ve never asked for repayment?”

“They’re my family.” I heard how thin it sounded.

He took off his glasses. He always did that when he planned to say something I wouldn’t like. “Your generosity is extraordinary, Louise. But you are enabling a system that harms you and ultimately harms them. The expectation will not end until you draw a boundary so bright it leaves an afterimage.”

I told him about the trust fund. His expression changed the way a sky changes when weather turns—a deepening you feel in your bones before the first drop falls. “That changes the context,” he said. “You need documentation. Notarized statements. A forensic accounting of your contributions and the opportunity cost.”

“Opportunity cost,” I repeated. The phrase steadied me the way a true name steadies a person in a fairy tale. It framed my loss in a language my father respected: money.

Joseph referred me to Victor Hernandez, a forensic accountant who looked like a high school cross-country coach and spoke with the patience of a judge. Victor sifted through five years of my financial life and built a narrative from receipts. He drew straight lines where I had drawn circles. He calculated lost investment growth with conservative assumptions. When he slid the final tally across the desk—$118,745 in direct contributions, plus a documented, defensible estimate of foregone gains—I felt a hot flush behind my eyes and did not blink.

“Most people don’t keep records this clean,” he said, not unkindly.

“Most people didn’t build their escape hatch out of spreadsheets,” I said.

He gave me a set of bound, notarized statements and a summary written in the dry, declarative style of insurance policies and court decisions. Words my father could not argue with without arguing with reality.

On the way home I stopped at a cafe on 300 South where the barista writes compliments on to-go cups. She drew a lightning bolt and scrawled, You are a storm with legs. I smiled into the steam. My phone buzzed again and again: Dad, then Megan. Don’t be difficult. We’re counting on you. Family doesn’t abandon family. Each message was a little rope thrown, meant to tie me back to the dock.

That night I sat on my living room rug and did three things I should have done years ago. I canceled the automatic payment on Megan’s car. I removed myself as an authorized payer on my parents’ utilities and HOA accounts. And I opened a new fund at my brokerage, labeled in a private joke that felt like a vow: MY FUTURE.

By noon the next day, the storm arrived. A voicemail from my mother, polite and trembling: your father is beside himself, the tax notice warns of a late fee, Megan can’t make the car payment, please call. A text from my father, stripped of any greeting: Call me immediately. This is unacceptable. A string from Megan: the bank says my payment bounced, are you trying to ruin my credit, what is wrong with you. I turned the phone face down and watched the candles on my chart flicker into patterns only my body believed.

Late afternoon, the front desk buzzed. “Ms. Walsh, your father is here and demanding—”

“Tell him I’m not available,” I said. When that didn’t work, I told them to call the police if necessary. I poured water into a plant that had wilted and watched its leaves lift, slow and stubborn.

Twenty minutes later, a cousin texted to ask why Uncle Greg had been escorted from my building by security. You okay? I stared at the screen and then typed the truth in a sentence I never thought I’d send: Family financial disagreement. His reply came fast. About time. The way they treat you and Megan—everyone sees it. It felt like stepping into sunlight after months indoors.

At seven, the doorbell rang. I checked the peephole. Megan stood in my hallway in a down coat and puffy indignation. I opened the door with the chain set and the habit of caution newly alive in me.

“What do you want?” I asked.

“What do I want?” She laughed without humor. “I want to know why you’re acting like a psycho and why Dad says you’re refusing to pay the taxes. You know they could lose the lake house.”

I thought of summers on the Bear Lake dock, her hair flung like a flag behind her as she ran, my father whistling, my mother setting out watermelon slices on paper plates. I thought of my teenage self in a red apron at the coffee shop, watching them drive away in the SUV I helped gas up.

“I’ve contributed nearly a hundred and nineteen thousand dollars over the past five years,” I said. “While Dad created a trust fund for you.”

Her face went through three weather systems in three seconds: surprise, then guilt, then heat. “That’s different,” she said quickly. “The trust is for my future.”

“And mine doesn’t matter?”

“You’ve always been the smart one,” she said. “You’ve got your whole trading thing.”

“Being capable is not a reason to be exploited.” The sentence landed like a gift I wish someone had given me at twenty.

“It’s not that much money.” The way she said it made clear she had never paid a bill from a balance that could run out.

“It is,” I said. “And it’s documented.”

“How do you even know about—” She stopped. “You saw the papers.”

“I did.”

She reached for my arm; I stepped back. “We’re family, Lou. We help each other.”

“Then use your trust fund to help,” I said, and closed the door gently between us. My hand shook after the latch clicked. I stood there and breathed until the shakes turned into a steady heat I understood as courage.

The family meeting was my father’s idea. He called it to “talk sense” into me, to “remind me of my responsibilities.” Word traveled through the network of aunts and uncles and cousins faster than lake wind. When I pulled into my parents’ driveway that Saturday, cars lined the curb. The house that had always felt like a stage felt more than ever like a set.

He was speaking when I walked in—something about duty and gratitude and the lake house being the “center of our family’s memories.” He faltered when he saw the slim black briefcase in my hand.

“I’m glad you decided to join us,” he said. “We were just discussing the situation with the vacation home.”

“You mean the situation where I paid the property taxes for five years while you funded a private trust for Megan?” I said. I didn’t sit. I placed the briefcase on the coffee table and opened it. Paper has a sound when it’s about to change the room. I passed bound summaries to every adult there, including my mother, who had lifted her gaze to me with something like apology and something like fear.

“What is this?” Aunt Catherine asked, flipping to the first page. She’d always been the one to ask what other people only thought.

“Five years of my contributions to this family,” I said. “Documented and notarized. Property taxes, car payments, medical bills, vacations. Totals and dates. There’s also a conservative calculation of lost investment growth based on the money I diverted to make these payments.”

Uncle Pete’s eyebrows rose as he read. My cousin Thomas, standing by the fireplace, glanced up and met my eyes with a look that said: keep going.

My father’s face had gone hard. “These are private family matters,” he thundered, as if volume could crush facts into dust.

“Exactly,” Uncle Pete said, straightening. “Family matters. Which is why both daughters should have been treated fairly.” He looked at my mother. “Were you aware of this?”

She flinched. “Greg handles the finances,” she whispered.

Catherine turned to my father. “You established a trust for Megan and not for Louise?”

“She doesn’t need—” he began.

“Need is not the measure of love,” Catherine said. The room went quiet enough to hear the furnace kick on.

My father stormed out, the screen door slapping behind him. My mother rose and followed. Megan stayed seated, eyes fixed on the document in her lap like it might rearrange itself if she stared hard enough.

People filtered into the kitchen in twos and threes. The house hummed with low conversations, the kind of murmur you hear after a verdict. When at last the crowd thinned, Aunt Catherine pressed my hand. “I’m sorry,” she said. “This should have been seen years ago.”

“I didn’t want to see it,” I admitted. “It was easier to call it loyalty.”

Three days later, my phone lit with a text from my father that contained four words and no punctuation: The property taxes are due. I stared at it until it became absurd, a bad joke told too many times.

I didn’t answer. I took a photo of the notarized summary—my name, the totals—and circled the number in red. I sent it without commentary and put my phone face down. Thirty minutes later, Megan called.

“Is it really that much?” she asked, voice small. “Dad showed me.”

“Yes,” I said, and when she cried I didn’t tell her not to. When she said, “I’m going to fix this,” I did not ask how, because I had learned not to hang my hope on other people’s promises.

The letter from my father’s attorney arrived the next afternoon, printed on paper that smelled like a bank. The taxes had been paid. There was a legally binding amendment to the deed. I owned twenty-five percent of the Bear Lake house. Attached was a note explaining that Megan had insisted on using her trust funds to cover the taxes and the legal costs of the transfer.

My father texted me: This wasn’t necessary. Family helps family.

I looked out at the thin line of the Wasatch, blue as veins, and laughed. At the shape of a life where fairness could be mistaken for cruelty. At the absurdity of a man so fluent in ledger lines he’d lost the plot of love.

That night my mother called to say she was proud of me. Her voice held the brittle music of something breaking and something being born. “I should have stood up sooner,” she said.

“Me too,” I said, and meant it.

Megan called the next day to say she’d demanded the trust be split equally. “Dad fought,” she said, “but Uncle Pete and Aunt Catherine backed me. He’s meeting with his adviser tomorrow.” She paused. “I’m sorry, Lou. Not just for the money. For believing the story that you didn’t need what the rest of us did.”

I pictured her as a kid on the dock, all knees and joy, before we learned the different roles scripted for us. Before I discovered that competence could be a cage. “Thank you,” I said.

In the weeks that followed, I rebuilt my life not from scratch but from honesty. I added to my new fund. I opened a separate savings account labeled BEAR LAKE TAXES—my share; I would pay it gladly in April because it would be mine to pay. I rewrote my budget like a love letter to a part of myself I’d neglected: future Louise with gray in her hair and mountains reflected in her eyes. I took a weekend (just me, no texts) and drove the Logan Canyon to the lake, the road cutting like a ribbon through aspen and lodgepole pine. The house looked the same—weathered siding, wraparound porch, the ceramic trout still crooked above the mantel when I unlocked the door with the new key a lawyer had couriered to my apartment. But something was profoundly different: I didn’t stand there as a guest waiting to please. I stood there as an owner prepared to choose.

I made coffee and drank it on the porch under a sky so blue it felt like a bruise healing. I swept sand from the entry and found, behind the boots, the old tackle box my father had kept since before I was born. I opened it and found the ledger he always carried—a spiral notebook with pencil columns of bait and lures and gas and notes about the weather and how many trout they’d caught. Numbers everywhere. He kept the story of his life in numerals and margins, a balancing of inputs and outputs that had made sense to him when I was still small enough to ride on his shoulders. Reading it that afternoon, I felt something loosen in me. It is possible to love a person and refuse to accept their version of fairness. It is possible to rewrite a ledger without erasing the summers a girl learns to swim in water cold enough to sting her lungs.

Before I left, I wrote my own note and tucked it into the back of his notebook.

Dad,

I know numbers are how you make sense of the world. Here are some of mine: five years, $118,745, and a boundary I should have drawn sooner. I will always love this lake. I will always love my family. I will pay my share. I won’t pay my sister’s any longer, and I won’t apologize for wanting a future that doesn’t run through your approval. Your daughter,

Louise.

On the drive home, with the radio low and the sun sliding behind the range, I considered how strange it is that we think money and love are related because they so often travel together. But money is a language. And like any language, it can tell the truth or tell a story that keeps you small. That week, I spoke truth—softly, then plainly, then without fear.

Spring came to the valley in slow greens. My mother started sending photos—peonies on the kitchen table, her knee brace finally off. Megan sent screenshots of her spreadsheets—actual spreadsheets—as she tracked her business expenses and drew a salary from work she did instead of from lines my father drew for her. My father wrote brief emails about repairs at the lake house. None ended in exclamation points. All were civil. It felt like a new language for him, too.

Joseph sent a simple congratulation when my new fund crossed a number I’d chosen because it meant something only to me. Victor mailed me a copy of his final report stamped CLOSED. The barista drew a thundercloud with a tiny heart.

On a hot afternoon in July, we met as a family at Bear Lake for the first time since the papers were signed. The water was crowded with boats and the air with the sound of summer. My father stood at the grill flipping burgers with the exactitude of a man running a jobsite. He handed me a plate without meeting my eyes and then, finally, he did. “We put your name on the deed,” he said, as if I might not have noticed the practical evidence of a moral shift. “You’ll need to sign for the new roof selection when the bids come in.”

“Happy to,” I said, and meant it.

He nodded once and then twice, as if agreeing with himself about something he hadn’t yet fully learned to say. My mother hugged me with her whole body. Megan splashed me from the shallows and grinned when I yelped.

That night I took the kayak out as the sky went the color of apricots. The water lapped the hull in gentle syllables. I thought of markets and momentum and how little predictability the world owes us, and how much steadiness we can still choose. I thought of the ledger I would keep for the rest of my life, written not in numbers but in boundaries and the rooms they make for love.

When the first star showed, I turned back to shore. The house lights came on, squares of gold in the blue. Someone laughed inside. A screen door eased shut. I beached the kayak and pulled it up past the wet line. For once, I didn’t check my phone. I didn’t check anything. I stood there with lake water around my ankles, feeling exactly how much I could carry and how much I would set down.

In the morning, I rose before anyone else and made coffee in the quiet kitchen. The ceramic trout still hung crooked. I left it crooked. Not every imperfection needs fixing to be loved. I poured a second mug, walked it out to the porch, and watched the day breathe open over the water. The mountains were old and reasonable. The lake looked like a new coin held flat in a giant palm. I sipped my coffee and smiled at the math of that moment: my share paid, my future funded, my family—this version of it—learning another way to count.

I’ve learned that love without boundaries becomes debt. I’ve learned that money without clarity becomes a story that eats you alive. And I’ve learned that drawing a bright line is not an act of war. It is an act of faith—faith that people can grow toward the truth, the way sunflowers grow toward light.

I rinsed my mug, locked the door behind me, and drove south as the first boat cut the water into a V that widened and widened until it touched both shores.

I used to think my origin story began that first summer I could tread water without panicking, out past the dock line where the lake went from turquoise to the deep blue that scared me. In truth, it began the winter I discovered there are patterns that look like chaos until you learn the rhythm inside them. I was nineteen, bone-tired from double shifts at the coffee shop and a late class that emptied into a campus so quiet the snow could be heard landing. In the library I found a shelf of finance books no one checked out; their spines weren’t cracked. I sat cross-legged on the gray carpet and read a chapter about support and resistance as if it were poetry. I liked the plainness of the terms. I liked the fact that the market, like a person, had places it would not go without force.

I didn’t have money to trade then. I watched. I charted by hand in a spiral notebook I bought with the last three dollars in my wallet, drew tiny candles with a mechanical pencil I borrowed from lost-and-found. I learned to see what most don’t because they are in a hurry: the way the second touch of a level is often the real tell, the way volume whispers the truth first. I learned to wait until my reasons stacked. Patience felt like power, like a secret muscle no one could take from me.

I made my first real trade years later on a spring morning that smelled like wet sidewalk. I had saved a tiny stake by choosing nights in over dinners out, by bringing food from home in a jar, by saying no so many times I didn’t recognize my own voice when I finally said yes. I placed the order and then stood up from my desk because I couldn’t bear to sit and watch the numbers do what they would. I washed a single bowl and a single fork and dried them with the care you give to ritual objects, as if I were lighting incense. When I came back, the price had moved exactly to my line and stopped, as if it had seen me draw it. I closed early, greedy. The profit was smaller than it could have been. But it was mine. Not given. Not taken. Mine.

People like my father believe markets are gambling and labor is the only honest work because a body can be seen sweating. But I’ve watched an index respond to a whisper of policy and I’ve watched a superintendent of a construction site count pallets of rebar with the same concentration; both are labor. The world wears more kinds of work than some men allow.

When I say I paid the property taxes, what I mean is I chose an entry, sized the risk, and set an alarm at 2:43 a.m. to exit a position that paid for a year’s worth of someone else’s memory. I pressed buttons no one saw. I made money in the margin between discipline and fear, then used it to buy us July.

The first time Megan asked for help with the car payment, she did it shyly, as if asking for a ride. “I’ll catch up next month,” she said, and maybe she believed it. I paid and told myself I was doing what a good sister does. The eighth time, she Venmoed me a heart emoji with no words. I stared at the cartoon heart until it turned ridiculous and then closed the app. I told myself stories about temporary rough patches the way a person tells herself the rain will stop at the next light.

Some memories I had kept small so they wouldn’t crowd the room. The night my Honda died on the shoulder of the I-80 in a squall and I called home and my father told me AAA was a better lesson than rescue; the morning after my all-nighter before finals, when I asked if I could skip the cousins’ brunch because my hands were shaking and my mother said attendance mattered; the way I learned to be the child who makes herself easier to carry. Love and obligation can look the same from far away. Up close, you can tell by the way the bill gets slid across the table.

If you had walked into Victor Hernandez’s office the day we built the ledger, you would have seen two printers spitting paper like sleet and a whiteboard covered in tidy columns and a woman learning to say out loud the cost of what she had swallowed. Victor is the sort of person who can explain compounding to a child and shame to an adult with the same calm tone. He never used the word “shame.” He used phrases like “documentable transfers” and “reimbursable expenses” and “non-reimbursable gifts” and somehow, in that taxonomy, my feelings found a place to sit without trying to run the meeting.

“What about the roof?” he asked, flipping to the page with the photos of shingles peeled back like the corners of a book.

“Include labor,” I said. “I hired and managed the contractor because Dad was in Reno on a bid.”

“We’ll categorize that as in-kind project management,” he said, writing it down.

The number at the bottom of his final page was not the largest number I had seen in my life, not compared to the P&L spikes I’d celebrated or survived. But it sits in a different part of the body. Market risk asks a question: did you honor your plan? Family risk asks another: are you worth anything if you stop paying?

I did not know how my father would answer that second question until the day he stood on my stoop demanding to be let in and then, when security asked him to leave, texted me as if the world had tilted off its axis. The thing about tilt is you can learn to stand on it. I silenced my phone and wrote in my trading journal: Your future is not a tip jar.

When my cousin Thomas texted from the family grapevine to say there would be a meeting, I laughed and then I practiced not shaking. On Saturday I put on the black pantsuit I wear when I don’t want to think about what I’m wearing. I tucked the briefcase under my arm and drove north, the mountains patient beside me. If the narrative of our family had a table of contents, that day would get a boldface chapter title.

My father tried to seat me on the couch with my mother and Megan like I was a junior associate waiting to be briefed. I stayed standing. I learned that posture from a hundred investor calls where the person on the other end assumes the woman is the assistant until she asks a question so precise it narrows the room.

“Louise,” he said, palms out as if calming a horse, “we’re talking about obligations.”

“So am I,” I said, and set the stack of summaries on the coffee table, one for each adult. Paper made a hush around us.

I watched their faces as they read. Aunt Catherine’s gift is that she moves from confusion to clarity with no detour into defensiveness; you can see it when it happens. Uncle Pete is slower but more stubborn once he crosses the river. My mother moves into the space where comprehension lives and then tucks herself behind someone else’s opinion for warmth. Megan reads like she is scanning for the part that tells her what to feel. My father doesn’t like to read in front of other people; he believes it gives the text too much power.

When he said “private family matters,” I surprised myself by smiling. “Exactly,” I said, and Aunt Catherine’s eyebrows went up because she is the only other person in the family who enjoys a clean rhetorical turn.

Later, in the kitchen, Catherine leaned against the counter, arms folded. “I knew there was a skew,” she said. “I didn’t know it was a business plan.” She took a breath I could hear. “You know you can file for a lien if it comes to it. Constructive trust, equitable interest.” She is not a lawyer; she has simply lived long enough to know the names of levers.

“I’m not trying to take the house,” I said. “I just won’t be covertly underwriting it anymore.”

She nodded. “Then say that sentence as many times as it takes until people stop pretending they didn’t hear it.”

The deed amendment happened faster than I expected because shame, when cornered, can move quickly. My father’s attorney sent language I didn’t hate and a courier with documents to sign. A notary watched me write my name and stamped the page with the little sound that stamps make, a sound that stills a thing in place. At the county recorder’s office, a woman with a bun and bright nails slid the papers into a slot and said, “Give it a day, hon, and then check the online map. You’ll see your name light up like a porch light.” She grinned. “Feels good, doesn’t it?”

It did. Not because I wanted property. Because I wanted accuracy.

That week I texted Megan and asked if she wanted to walk around Liberty Park. She showed up in leggings and a hoodie and the expression she wore in middle school when she got caught whispering. We walked the loop where runners fly past like purposeful geese. We didn’t talk for the first half-mile. On the second, she said, “Do you think Dad loves me more?” The question knocked the breath from me because I had expected defenses, not the core.

“I think he knows how to feel needed by you,” I said. “And he never figured out how to feel that with me without making me small.”

She kicked at a leaf that had held its red all the way to January. “I could have asked more questions. About where the money came from. About why you were always the one swiping your card.”

“We were given roles very early,” I said. “That doesn’t excuse us from reading the script before we perform it.”

She laughed through her nose. “You always talk like this when you’re trying not to be mean.”

“I’m trying to be precise. Precision is kindness with numbers.”

She stopped and looked at me. “I told Dad to split the trust because I want to choose you, not just the things you pay for.”

“You didn’t have to do that.”

“No,” she said. “But I did.”

The day the trust papers changed, I was not there. I imagine it like this: my father in his adviser’s office, in a chair too soft for his pride, speaking in verbs like “allocate” and “preserve” because nouns like “favoritism” and “repair” would make him itch. The adviser—a man who has seen many fathers age into better versions of themselves and many fathers refuse—slides options across the desk. A calculation gets done. A phone call is made to a bank where the lights never go off. A woman with a headset and a cheerful voice reads a disclosure in the tone of a lullaby. Somewhere a number moves from one column to another, and a story loosens a knot.

I did not grow up in a family that apologized. We did gestures instead of words. My father tilled the garden hard the year he missed my national honor society ceremony. My mother left a plate of cut fruit on my desk the morning after our worst fight and called it “snack” as if nourishment weren’t the language of apology. So when my father texted me about the taxes again, not with contrition but with expectation, I widened the distance between his sentences and my worth and filled the empty space with air I could breathe.

When summer came back, I found myself driving to Bear Lake alone on a Monday because my calendar said I could. I stopped at a roadside stand where a boy with a sunburn sold cherries by the handful and put the bag on the passenger seat like a companion. At the house, I changed the air filter, replaced two AC return grates that had rusted, and wrote the new parts and dates on a sticky note I put in the ledger with the ceramic trout smiling down as always. Domestic maintenance used to be invisible labor I provided; now it felt like a practice, a way of telling the house I saw it.

In the late afternoon, a pickup rattled into the driveway and my father climbed out wearing the cap with his company logo faded to ghost letters. He moved more slowly than the man in my memory who could shoulder a sheet of plywood by himself and whistle all the way up the stairs.

“I didn’t know you’d be here,” he said.

“It’s on the shared calendar,” I said. “I added you.” The tech-literate jab landed; he winced and half-smiled because he can take a light hit.

We stood with the truck between us like a neutral country. Somewhere on the lake a speedboat roared and then shushed.

“Your note,” he said finally. “In the notebook. I read it.” He scrubbed a hand over his face. “I keep ledgers because it makes me feel like a man who knows what he’s doing. Felt like that since my own dad, God rest him, ran tabs at three places and paid none of them on time.” He looked at me then, really looked, the way men look at their daughters when they realize they’ve grown into people who could hold them accountable without breaking love. “I forgot the ledger that matters doesn’t balance unless both names are on the page.”

I didn’t say anything. Some moments are stronger when they’re not framed.

He took a breath that sounded like he had been holding it since I was born. “I can’t promise I’ll say the right things. I can only say I’m going to try to stop assuming you’ll fix what I break.”

“That’s a start,” I said.

We worked companionably for an hour replacing the cracked trim on the back door. He measured; I cut; he nailed; I caulked. The rhythm was good. There are ways of speaking that happen through tasks, through shared focus, through not forcing a resolution with a speech. When we finished, we stood back and admired the straightness of the line as if we’d hung a painting.

I drove back to the city in the blue hour, thinking about how reconciliation is less a party than a series of chores you agree to do together without keeping score.

Not everything got better because the deed changed and a trust rebalanced. The group text still pinged with subtweets. An aunt I love told me she “didn’t like all this money talk,” as if the silence had been a virtue. A cousin asked me for “a little advice” about crypto and got huffy when I asked about his risk limits. My mother still defaulted to smoothing rough spots with fudge, literal and metaphorical. But the shape of the family shifted a few degrees toward honest, and sometimes that is the miracle—small, measurable, undeniable.

On my desk at home, I kept the trading journal open to a page with two columns I had drawn by hand. On the left: price action. On the right: family action. Under price action, I logged entries and exits, reasons and emotions. Under family action, I logged requests and replies, reasons and emotions. It sounds clinical. It saved me. I could see on paper the moment a pattern tried to reassert itself: a last-minute ask, a guilt-laced reminder, a story about “we,” none of which included me as a person with desires and limits. Writing it down gave me the distance to make a choice instead of a reflex.

In August, Megan invited me to the grand opening of her small storefront—a boutique yoga-and-wellness space on a sleepy street that smelled like fresh paint and possibility. I stood by the fern wall taking in the chalkboard price list and the earnest tea selection and waited for the part where a sister would feel petty. It didn’t arrive. She had built something. She had put hours into a place that could be counted in calluses. She walked me through the scheduling software she’d learned to use and showed me the spreadsheet where she tracked sales by category and I felt a complicated pride that didn’t require me to flatten myself to fit inside it.

“I’m paying my own car now,” she said casually, which is how you say a thing when you are proud but afraid of scaring it if you speak too loudly.

“I know,” I said. “The bank stopped emailing me.”

She laughed. “I’m sorry.”

“Consider it a closing bell,” I said. “A happy one.”

That night, after the last guest left and the fairy lights made the space look like a wish you might actually get to keep, we swept the floor together. She said, “Do you think I should invest in a second reformer or save for three months first?” It was a simple question and a small one but it carried a world inside it. She was asking me as a person who knows things, not as a bank that dispenses grace on demand. We sat on the floor and opened her laptop and built a little model, month-by-month, playlist-of-cash-flows style. We made a plan where she could see both risk and runway. This is how repair looks: not in a single cinematic apology but in shared spreadsheets on a floor that smells like lemon cleaner and hope.

When September turned the canyon aspens to coins, Joseph emailed to say my MY FUTURE fund had crossed the target we set the week I stopped paying other people’s bills. He used a single exclamation mark because he knows my feelings about punctuation and restraint. I walked to the bakery on the corner and bought a croissant and ate it slowly, not as a treat but as a marker: here is where you decided and here is what it made.

I visited my mother alone one Sunday. She made pot roast the way she has since we were kids, onions first until they go translucent, then the meat, then the carrots, then the potatoes, each thing in its order. We sat at the table and she said, “Your grandmother used to hide her egg money in the hem of the curtains. Did I ever tell you that?”

“No,” I said, because she hadn’t.

“Your grandfather would have used it for cigarettes. She called it her ‘just because’ money. Just because you never know. Just because a woman needs to prove she can buy a bus ticket and a dress without asking. I think I forgot that when I watched you be good at providing. I mistook abundance for immunity.”

I reached across the table and took her hand, the skin paper-thin and warm. “We learned what we were taught,” I said. “Now we’re learning again.”

She nodded. “I told your father I won’t be the messenger anymore. If he wants to ask you for something, he can ask you himself. He hasn’t liked that. But he’s trying.” She smiled a little. “He replaced the broken drawer rail in my dresser last night without being asked. Thirty-eight years, and I still find new ways to love him when he does a simple thing that is not simple.”

On the first snow of November, I drove to the recorder’s office website and pulled up the parcel map because I am a person who likes to look at the official version of a thing. The square with the lake frontage had four names now. Seeing my own in the county’s font gave me a steadiness I had not anticipated. The world had caught up to the reality inside me.

At Christmas, we did not pretend. We agreed on a budget. We stuck to it. We ate lasagna because none of us wanted to cook a turkey and call it tradition if it didn’t make anyone happy. We went around the table and each said a thing we’d changed our minds about this year; my father said he had started to think maybe retirement is not failure but another kind of work. We clapped, not because we agreed but because we recognized the risk it takes to say you were wrong to the people who taught you how to be right.

There will be other meetings. There will be other bills. There will be times when my father forgets and slides a responsibility across the table as if it comes with my name already printed on the line. When that happens, I will push it back across the polished wood and feel the wobble and then the settle as it comes to rest on his side. I will pay what is mine. I will pay it gladly. The rest belongs to the people it belongs to. This does not make me cold. It keeps the coffee warm for the mornings I wake before dawn and watch the market open like a curtain and listen to the sound numbers make when they tell the truth.

Some nights, when the city is quiet and the Wasatch has the moon printed on it like a watermark, I write letters I don’t send. One to the girl I was at nineteen: You can survive on less but you don’t have to forever. One to Megan at sixteen: You are not fragile; don’t let anyone enjoy treating you that way. One to my father at forty: I am not your second chance at getting fatherhood right by doing it wrong to me. One to my mother: I see the way you carry all the parts that didn’t fit into the stories we told and I think you are brave.

I tuck those letters into the ledger that holds my budgets. I do not need them to be read to be real. There is relief in naming what was once unnamed. There is power in the smallest of accurate words: no; mine; enough.

In the spring, a realtor friend sent me a listing for a narrow A-frame an hour east, a triangle house tucked in sage and sky. I drove out on a weekday when the light had that clean March clarity and walked the property lines with a measuring wheel I brought because the truth is I enjoy measuring things. I stood in the doorway and pictured a desk by the window where a person could trace a chart and also watch a hawk tilt one long wing and choose a thermal. I did not make an offer. Not yet. I am learning that you can want a thing and not rush to own it. I am learning that pleasure lives in the power to choose.

In early June, I took the kayak out again at Bear Lake just as the first boats wrote white Vs on blue glass. I paddled farther than I ever had, until the houses were toy models and the dock where we taught ourselves to cannonball looked like an underline. I rested the paddle and let the wind turn me to face shore. If you’d seen me from the porch, you might have thought I was lost. I wasn’t. I was where you go when you have drawn your bright line and found that it does not fence you in. It frames the horizon.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

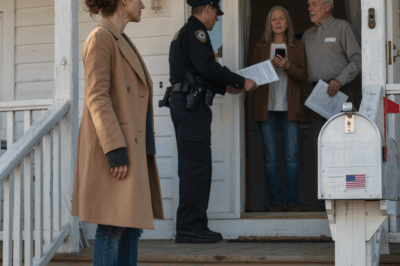

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load