The morning after the funeral, the kitchen felt too bright for grief. The bay window threw a clean square of light across the oak table, catching on the rim of Margaret’s favorite mug and the little flag magnet on the refrigerator, the one we bought years ago at a gas station off I‑95. Condensation slid down a pitcher of iced tea I hadn’t had the heart to put away. Somewhere down the block, a neighbor’s radio drifted Sinatra over the hum of leaf blowers and delivery trucks. I stood in my socks, palms warm around a fresh pot of coffee, and thought about how silence in a house has a sound of its own.

I didn’t tell my son about the oceanfront property on Cape Cod my wife left me.

Three days after Margaret’s funeral, Steven walked into my Boston kitchen and said we needed to talk about getting me settled somewhere more manageable. I simply nodded and poured him coffee. That evening, after he left, I opened the envelope Margaret had hidden in her desk and made a call to Hyannis.

The funeral had been on a Tuesday. By Friday morning, Steven and his wife, Brittany, were sitting in my living room with a real estate agent. Margaret had been gone exactly seventy‑two hours.

“Dad, we know this is hard,” Steven said, adjusting his tie. He’d worn the same tie to his mother’s service. “But this house is too much for you. Four bedrooms, that big yard, all these stairs. Mom would want you somewhere safe.”

Brittany nodded, her perfectly manicured hand resting on a folder full of retirement community brochures. “We’ve done the research, Thomas. There’s a lovely facility in Framingham. They have activities, meal plans, a nurse on staff twenty‑four seven.”

The real estate agent, a young woman named Ashley, smiled at me with practiced sympathy. “Mr. Morrison, in this market, a house like this could sell in days. We’re talking two‑point‑five, maybe two‑point‑six million. Think of the security that would give you.”

I looked around the room where Margaret and I had hosted thirty years of dinner parties, where we’d celebrated birthdays and anniversaries, where she corrected thousands of student papers while I graded my own. The morning light came through the bay window exactly as it always had.

“I need time to think,” I said.

Steven leaned forward. “Dad, we can’t wait too long. The market’s hot right now, and honestly, the maintenance on this place, the property taxes—it’s going to drain your savings. We’re trying to help you.”

“Your son is right to be concerned,” Ashley said. “At your age, liquidity is important.”

I was sixty‑eight years old. Margaret had been sixty‑six. We’d planned to have another twenty years together, maybe thirty. Instead, I got three weeks’ notice. A headache that wouldn’t go away. Then the diagnosis, then hospice, then a hole in the world where she used to be.

“I’ll think about it,” I repeated.

After they left, I sat in Margaret’s study. She’d been a literature professor who specialized in New England maritime authors. The walls were lined with books, most of them annotated in her small, precise handwriting. Her laptop sat on the desk, password‑protected, but I knew the password. I’d always known it.

I opened the laptop and found the folder labeled: For Thomas When I’m Gone.

Inside were three documents. The first was a letter. “My dearest Thomas,” it began. “If you’re reading this, I’m gone and Steven has already started circling. I know my son. I know what he’ll do, so listen carefully.”

I read the letter three times that night. Then I read the second document, a property deed. Then I read the third document, a contract with her publisher regarding royalty payments. Then I called the lawyer in Hyannis, whose number Margaret had written at the bottom of the letter. His name was Robert Chen.

He’d been expecting my call. “Professor Morrison, I’m so sorry for your loss. Margaret was an extraordinary woman. She came to see me two years ago to set this up.”

“Two years ago,” I said. “She knew she was sick two years ago?”

“No,” Robert said gently. “She told me she just wanted to be prepared. She said Steven had a way of making everything about money, and she wanted to make sure you’d be protected.”

I set the phone on the desk and stared at the flag magnet on the fridge through the doorway, its little enamel colors winking in the light. Margaret, meticulous even in leaving.

I made myself a simple promise then: I would not be managed out of my own life.

On Monday, Steven came back. This time, he brought Brittany and a lawyer of his own.

“Dad, we’ve been thinking,” Steven said. “Maybe you shouldn’t live alone at all, even in a retirement home. What if you moved in with us? We have that basement suite in Wellesley. It’s finished. Has its own bathroom. You’d be with family.”

I imagined myself in their basement, listening to Brittany’s footsteps above my head, eating dinner at their table when invited, trying to stay out of the way.

“That’s very generous,” I said.

“And about the house,” Brittany added. “We could help you manage the sale. Steven has financial expertise, and I know the real estate market. We’d make sure you got every penny, minus a small fee for our time, of course. Family rates.”

“Of course,” I echoed.

Their lawyer, a thin man with wire‑rimmed glasses, slid papers across my kitchen table. “This is just a power of attorney, Mr. Morrison. It would allow Steven to handle the sale on your behalf, manage the proceeds, make sure your finances are in order. Given your age and recent loss, it’s really just sensible planning.”

I looked at the papers. I looked at my son. He had Margaret’s eyes, but none of her warmth. When had that happened, or had it always been there and I simply refused to see it?

“I need to show you something first,” I said.

I went to Margaret’s study and came back with a photo album. Inside were pictures from 1987, when Steven was seven years old. Margaret and I stood in front of a small shingled cottage on Cape Cod, the Atlantic stretching behind us. Steven, a child, building sand castles on a beach littered with snail shells and driftwood. A younger Margaret, her hair still dark, smiling at the camera.

“Do you remember this place?” I asked Steven.

He barely glanced at the photos. “That old cabin. Dad, that was decades ago. What does that have to do with anything?”

“Your mother loved it there,” I said. “We went every summer until you turned twelve and decided you were too old for family vacations.”

“It was boring,” Steven said. “There was nothing to do. No internet, no cable—just rocks and seagulls. Dad, focus. We’re talking about your future, not some nostalgia trip.”

I closed the album. “You’re right,” I said. “Let me think about these papers. Give me a week.”

Brittany’s smile tightened. “Thomas, we really think you should act quickly. The housing market won’t stay this hot forever, and honestly, at your age, procrastination isn’t wise.”

“A week,” I said again.

After they left, I called Robert Chen. “They’re moving faster than Margaret predicted,” I told him.

“Are you ready to proceed with her plan?” he asked.

I looked around the house. Margaret was everywhere and nowhere—her coffee mug still in the sink, her coat still hanging by the door, her absence so loud it drowned out everything else.

“Yes,” I said. “I’m ready.”

The next day, my granddaughter Claire came to visit. She was in her second year at Boston University, studying art history. She looked like Margaret—same high cheekbones, same way of tilting her head when she was thinking.

“Grandpa, are you okay?” she asked. “Dad said you’re selling the house and moving to a home. Is that what you want?”

I made us tea the way Margaret always had. “Claire, let me ask you something. Are you happy at school?”

She shrugged. “It’s fine. The classes are good, but honestly, I’m not sure what I’m doing it for. Art history isn’t exactly a practical degree, according to Dad. He keeps telling me I should switch to business or finance—something useful.”

“What do you want to do?” I asked.

“I want to work in museums,” she said. “Or maybe archives. I love old things—stories about where things came from. But Dad says that’s not a real career. He says I’m wasting my time and his money.”

I thought about Margaret, who’d spent forty years teaching literature to students who mostly just wanted to pass English 101 and move on. She’d loved every minute of it.

“Claire,” I said, “how would you feel about taking a year off school?”

She blinked. “What?”

“I’m not selling this house to move to a retirement home. I’m leaving Boston, and I could use some help. Your grandmother left me something, and I need someone I trust to help me figure it out. It would mean leaving school for a while, maybe a year, but I’d pay you, and you’d have time to figure out what you really want.”

“Leaving Boston? Going where?”

“Cape Cod,” I said.

Her eyes widened. “That place from the old photos with the ocean?”

“That place,” I confirmed.

“Dad will lose his mind,” she said, but she was smiling.

“Probably,” I agreed. “Are you in?”

She didn’t hesitate. “I’m in.”

That night, Steven called. “Dad, I talked to Ashley. She can list the house this week. We need to get you packed up and moved. Brittany found a great retirement community. They have an opening in two weeks.”

“I’ve made a decision,” I said. “I’m not selling.”

Silence on the other end of the line. Then, “What do you mean you’re not selling? Dad, we discussed this. You can’t manage this house alone. Be reasonable.”

“I’m not staying here either,” I said. “I’m moving to Massachusetts’ south shore. Your mother left me a property there, a house by the ocean. I’m going to live in it.”

“What property? Mom never mentioned any property on Cape Cod.”

“She didn’t mention a lot of things,” I said, “but she was very thorough.”

“Dad, listen to me. You’re not thinking clearly. You just lost Mom. You’re grieving. You can’t make major decisions right now. This is exactly why you need family to help you.”

“I appreciate your concern,” I said, “but my mind is made up.”

“We’re coming over tomorrow,” he said. “We need to talk about this face to face. Don’t do anything until we talk.” He hung up before I could respond.

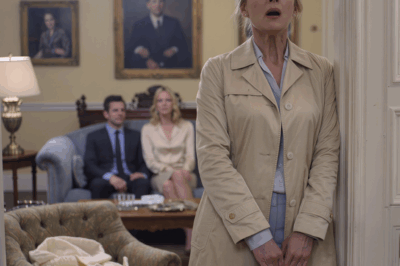

The next morning, Steven and Brittany arrived at eight a.m. With them was a doctor, a young man with a briefcase and a concerned expression.

“Dad, this is Dr. Harrison,” Steven said. “He’s a geriatric specialist. We just want him to do a quick evaluation—to make sure you’re okay to be making these kinds of decisions.”

I looked at the doctor. “Did my son tell you I have a cognitive problem?”

Dr. Harrison shifted. “He expressed some concerns about your judgment. Given your recent loss and your age, it’s not unusual to see changes. I’m just here to run some simple tests.”

“I don’t consent to any tests,” I said. “And I’d like you to leave my house.”

“Dad, don’t be difficult,” Brittany said. “We’re trying to help. If you’re competent, the tests will prove it. Unless you have something to hide—”

“I have nothing to hide,” I said. “But I also have no obligation to prove my competence to you. Dr. Harrison, I appreciate that my son brought you here, but I’m not your patient, and I’m not submitting to evaluation. Good morning.”

The doctor left. Steven stayed.

“What’s really going on, Dad?” he asked. “Is this about money? Are you worried about your finances? Because Brittany and I can help. We can manage everything for you. You don’t need to worry.”

“I’m not worried,” I said.

“Then why are you running away to the Cape? Why are you refusing to sell this house when you could have millions in the bank? Why are you taking Claire out of college? Yes, she told us. What kind of grandfather derails his granddaughter’s education for some fantasy about living by the ocean?”

“The kind who listens when his granddaughter says she’s not happy,” I said. “The kind who respects her choice.”

“Her choice? She’s twenty. She doesn’t know what she wants, and you’re enabling her to throw away her future. Do you know how much her tuition costs? Do you know what we’ve invested in her education?”

“Do you know what she wants to do with her life?” I asked. “Have you ever asked her?”

Steven stood up. “I’m not going to let you do this. If you won’t be reasonable, I’ll take legal action. I’ll prove you’re not competent to handle your affairs. I’ll get guardianship. This house is family property, and I’m not letting you give it away to some fantasy.”

“Family property,” I said quietly. “Your mother and I bought this house in 1982. We paid every mortgage payment. We paid for every repair. You didn’t contribute a single dollar. This house is mine, Steven—not yours. And what I do with it is my decision.”

“We’ll see about that,” he said, and left.

I called Robert Chen again. “They’re going to fight this,” I told him.

“Let them,” he said. “Margaret made sure everything was airtight. The Cape house is in your name only. It was purchased twenty years ago with her inheritance from her parents, before you moved to joint finances. They can’t touch it. And the royalties from her books go directly to you as her widower. It’s all documented.”

“What about the Boston house?” I asked.

“That’s where it gets interesting,” Robert said. “Margaret did some research. She discovered that your foundation is failing. Did you know that?”

“I didn’t.”

“She hired an inspector to check two years ago when she first came to see me. The foundation has major structural issues. It’s going to cost at least four hundred thousand to repair, maybe more. And that’s not all. The city is doing a property tax reassessment in your neighborhood. Your taxes are about to triple, and your homeowners association has a special assessment coming for infrastructure repairs—another fifty thousand due in six months.”

“How did Margaret know all this?” I asked.

“She read every letter, every notice, every piece of mail that came to the house,” Robert said. “And when something concerned her, she investigated. She knew Steven would come after this house the moment she died. She wanted to make sure you understood what you’d actually be giving him.”

I thought about Margaret, quietly gathering information, quietly preparing, protecting me even after she was gone.

“So if I sell the house,” I said slowly, “whoever buys it is going to face a financial nightmare.”

“Correct,” Robert said. “But here’s what Margaret suggested: you transfer the house to Steven now as a gift. You don’t sell it. You give it to him before the reassessment goes through, before the foundation report goes public, before the special assessment notice lands. You give it to him as his inheritance early.”

“And then?” I asked.

“And then you take Claire and you move to Cape Cod. You live in the ocean house, which is paid off and has no issues. You live on Margaret’s book royalties, which will give you about two hundred eighty thousand dollars a year for the rest of your life. Margaret’s books are used in university courses across the United States. The royalties are steady and recurring.”

“And Steven?” I asked.

“Steven gets exactly what he wanted,” Robert said. “The house—all of it. His name on the deed, his problem to deal with.”

I was quiet for a long time.

Greed doesn’t read the fine print.

The paperwork took two weeks. During that time, Steven called every day, sometimes twice, demanding I reconsider. He threatened lawyers. He threatened to have me declared incompetent. He showed up at my door with more retirement brochures. I stayed calm. I stayed quiet. I let him talk himself into certainty.

And then, on a cold Monday in March, I invited him to the house.

“I’ve thought about what you said,” I told him. “You’re right. I can’t manage this place alone, and Claire needs to be in school, not following her grandfather on some impractical adventure. So I’m going to give you what you want.”

His expression shifted from suspicion to surprise to triumph.

“You’re selling?”

“Better,” I said. “I’m giving the house to you now as an early inheritance. It’s yours.”

Brittany’s eyes went wide. “Are you serious?”

“Completely serious,” I said. “My lawyer drew up the transfer papers. The house goes to you free and clear. No sale, no division of proceeds, no complications. It’s your property now.”

I slid the papers across the table. Steven read them twice, looking for the catch, but there was no catch. The house was being transferred entirely to him.

“What about you?” he asked. “Where will you live?”

“I have Margaret’s life insurance,” I said. “It’s enough for a small apartment somewhere. I’ll be fine. You and Brittany will have the house. You can live here, sell it, rent it—whatever you want. It’s your property now.”

He signed. Brittany signed. They practically ran out of the house to file the paperwork before I could change my mind.

I smiled and signed everything.

But he didn’t know about the ocean house.

Claire and I packed everything that mattered into a moving truck: Margaret’s books, the photo albums, my research files, Claire’s art supplies. Everything else we left for Steven. We drove south and then east, taking the long way down Route 6 as if the road itself could stretch us into new shapes. We stopped for clam chowder in Plymouth, and that night we split a plate of fish and chips in a small diner with a neon lobster blinking in the window.

The house on Cape Cod sat on three acres overlooking the Atlantic. It was exactly as I remembered it, only better. Margaret had renovated it over the years, updating the plumbing and electrical, adding skylights and a modern kitchen. The walls were lined with windows. You could hear the waves from every room.

“Grandpa,” Claire breathed. “This is incredible.”

We spent the first week unpacking, exploring the property, walking the beach. The nearest town was fifteen minutes away—small but friendly. The neighbors brought casseroles and welcomed us to the Cape. I set up Margaret’s books in the study. I framed photos of her and hung them on the walls. Every morning I walked down to the beach, sat on the rocks, and talked to her. I told her about the house, about Claire, about how right she’d been about everything.

Claire enrolled in a couple of online courses to maintain her enrollment. She started painting again, something she’d stopped doing when Steven told her it was a waste of time. She painted the ocean, the rocks, the light on the water. Her work was—there is no other word—extraordinary.

The royalty payments came every quarter, deposited directly into my account: two hundred eighty thousand dollars a year, like clockwork. Margaret’s books would be taught as long as American literature was studied. Her words would support me for the rest of my life.

Three months after we left Boston, Steven called.

“Dad, we need to talk,” he said. His voice was tight with anger.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, though I knew.

“What’s wrong? What’s wrong? The foundation of this house is collapsing. The inspector says it needs four hundred thousand in repairs, maybe more. And the property taxes just tripled—tripled. And there’s a special assessment from the homeowners association for fifty thousand due next month. You knew about this. You knew. And you gave me this disaster on purpose.”

“I didn’t know,” I said calmly. “Your mother handled all of that. I just knew it was too much for me to manage.”

“You set me up. You gave me a money pit and then ran away to your little beach house. How did you even afford that place? Where’s Mom’s life insurance money going? I have a right to know. I’m your son.”

“The beach house was your mother’s,” I said. “She bought it twenty years ago with her parents’ money. It’s mine now. As for her life insurance, that’s also mine. And as for being my son—you’re right. You are. But you stopped acting like it the day your mother died.”

“This is fraud,” he hissed. “I’m going to sue you. I’m going to take everything you have.”

“I encourage you to talk to a lawyer,” I said. “You’ll find that everything was done legally. The house was transferred to you as a gift. It’s yours now. Congratulations.”

He hung up. He called back twice more over the next week, each call angrier than the last. I stopped answering.

Through Claire, I heard what happened next. Steven tried to sell the Boston house, but no buyer would take it once the foundation issues were disclosed. He tried to get a loan to fix the foundation, but the bank wouldn’t lend against a property with that much damage. He and Brittany fought constantly about money. She blamed him for taking the house without having it inspected. He blamed me for “tricking” him. Eventually, they sold it for less than the value of the land alone, taking a massive loss just to get out from under it. The buyer was a developer who planned to tear it down and rebuild.

Everything Margaret and I had built together in that house would be destroyed, but it was Steven who destroyed it, not me.

Claire and I stayed on the Cape. She finished her degree online, then got a job at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, doing exactly what she’d always wanted to do—cataloging paintings, handling archives, learning the quiet language of objects. She rented a small apartment in New Bedford, but came home every weekend to paint and walk the beach.

I wrote my own book, finally—a memoir about teaching literature for forty years, about meeting Margaret in graduate school, about building a life together. It wasn’t a bestseller, but a small New England press published it and the reviews were kind. Margaret would have been proud.

Steven never called again. Sometimes I thought about reaching out, but I never did. He’d made his choices. I’d made mine.

On what would have been Margaret’s sixty‑ninth birthday, Claire and I took flowers down to the beach. We didn’t have a grave to visit—Margaret had been cremated and her ashes scattered here, in the ocean she loved—but we sat on the rocks and told stories about her.

“Do you think she knew it would end this way?” Claire asked. “With Dad losing everything and us out here?”

“I think she knew exactly how it would end,” I said. “She knew Steven would take the bait. She knew greed would blind him. She knew he’d never check, never question, never think past the immediate value of the house. And she knew I needed to be free of it.”

“She saved us,” Claire said quietly.

“Yes,” I agreed. “She did.”

The sun set over the Atlantic, painting the sky in ribbons of orange and gold. The waves kept time against the rocks. Somewhere to the west, back in Boston, Steven was probably still bitter, still angry, still blaming everyone but himself for his choices. But that weight—finally, blessedly—was not mine to carry.

Margaret had given me a gift. Not just the house or the money, but freedom. Freedom from obligation to people who saw me as an asset instead of a father. Freedom from a house that had become a burden instead of a home. Freedom to spend whatever time I had left doing what I wanted, with someone who loved me for who I was.

I thought about that last letter she’d written me. The ending had stayed with me:

“Thomas, by the time you read this, Steven will have already shown you who he is. I’m sorry I won’t be there to protect you, but I can do this much. Don’t let guilt control you. Don’t let obligation trap you. You’ve spent sixty‑eight years being a good man, a good husband, a good father. You’ve earned the right to be free. Take Claire. Take the house. Take the life I’m leaving you. And live it fully, my darling. Live it for both of us.”

I had lived by duty my whole life—teaching students who didn’t care, grading papers at midnight, serving on committees, playing the small politics required to survive academia. I had been a good father to Steven, even when he made it difficult. I had been a devoted husband to Margaret through better and worse, sickness and health.

Now, finally, I was just Thomas, a man with a house by the ocean, a granddaughter who visited on weekends, and enough money to live comfortably until I died. A man who spent his days reading, writing, walking the beach, and talking to his dead wife.

It wasn’t the life I’d planned, but it was a good life—maybe even a great one.

The last light faded from the water and Claire and I walked back to the cottage. Through the windows, I could see the warm glow of the lamps we’d left on. Home. Real home.

Back inside, I set the kettle on and reached for Margaret’s mug. The flag magnet clicked against the fridge door when I closed it, a tiny, faithful sound.

Justice doesn’t have to be loud; sometimes it’s the softest noise in the room.

For the first time in years, I slept without alarms, without lists, without negotiations waiting for me in the morning. Margaret had been right about everything. Steven had shown his true nature within days of her death. He’d tried to control me, to trap me, to reduce me to a problem he could solve with paperwork and real estate transactions. He’d never once asked what I wanted. He’d never once considered that I might have plans of my own.

And in trying to take everything, he’d ended up with nothing but debt and bitterness.

I, on the other hand, had ended up with everything that mattered: peace, purpose, a place to belong, and the knowledge that Margaret, even in death, had loved me enough to plan for my freedom.

I opened my laptop in the morning light and began to write again. The waves kept their careful rhythm outside. The kettle clicked off. Claire’s paintbrushes rattled in a jar on the counter as she came in from the porch, hair wind‑tossed, cheeks pink from the salt air.

“Coffee?” I asked.

“Always,” she said, grinning.

I poured for both of us. Sinatra drifted in from a neighbor’s radio again, all brass and velvet. The house felt lived in. The study smelled like paper and salt. The flag magnet held a grocery list and a photo booth strip of Margaret and me, our faces pressed together, laughing like people who trusted the future.

Margaret’s letter hadn’t just saved me; it had taught me the only lesson she’d never been able to make me learn while she was alive: that it is not unkind to refuse the cruelty of others.

A single sentence held me steady as the tide: I will not be managed out of my own life.

We kept it simple. Claire took the ferry when she needed a change of scenery, then drove back down the peninsula at dusk. I mailed the royalty statements to a folder marked with Margaret’s neat label maker tags and did my taxes with a calm I had never known. I paid the property taxes on time and sent a thank‑you note to Robert Chen for the tenth time, even though he insisted it wasn’t necessary.

When the first nor’easter of the season blew in, the house held like a ship Margaret herself had caulked. I brewed tea and watched the horizontal snow erase the horizon. The next morning, the light after the storm was so clean it felt like a new year.

A week later, a small package arrived—a slim, clothbound volume from Margaret’s publisher, a commemorative edition with a dedication page I hadn’t known about. Under the title, in tiny print, the words: For Thomas, whose patience is a kind of lighthouse.

I set the book on the desk, opened the curtains, and let the ocean fill the room.

Home isn’t the deed; it’s the light that meets you at the door.

News

At the airport my ticket was canceled, i checked my phone, mom texted “have fun walking home, loser!” then dad said, “stop acting poor, take a bus like you should.” so their faces, went pale when…

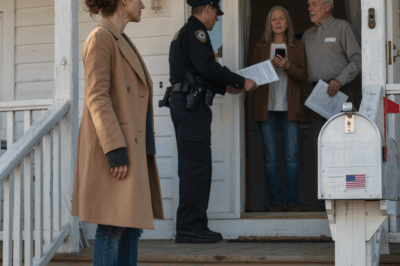

My family always said I was too sensitive, right up until the sheriff’s cruiser rolled slow past the mailbox with…

My younger brother texted in the group: “don’t come to the weekend barbecue. my new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” my parents spammed likes. i just replied: “understood.” the next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My little brother dropped the message into the family group chat on a Friday night while I was still at…

My dad said, “We used your savings on someone better,” and he didn’t even blink. I thought I knew what betrayal felt like—until the night my entire family proved me wrong.

My dad looked straight at me and said, “We spent your savings on someone better.” He didn’t even blink when…

At dinner, my family said “you’re not welcome at christmas it’s only for parents now.” i smiled and booked a luxury cruise instead. when i posted photos from the deck, their messages…didn’t stop coming

My parents’ kitchen smelled like cinnamon, ham glazing in the oven, and the faint bite of black coffee that had…

I walked out of work to an empty parking spot. my first car was gone. i called my parents panicking. “oh honey, relax. we gave it to your sis. she needs it more.” my sister had totaled 3 cars in five years. i hung up…and dialed 911…

I walked out of work balancing my laptop bag and a sweating plastic cup of gas station iced tea, the…

My Son Gave Up His Baby : “she’s deaf. we can’t raise a damaged child” “we gave her up for adoption, nothing you can do!”. i walked out and spent years learning sign language and searching for her everywhere. my son thought i’d given up… then one day

My son’s voice broke my heart before I even heard what he had done. I was sitting in a business…

End of content

No more pages to load