I grew up believing that the quieter you are, the more carefully you can hear the people you love. You learn their rhythms: the clink of a spoon on a mug when a thought is coming, the way a shoe squeaks on hardwood when someone is about to apologize, the exact timbre a voice takes on when a boundary is about to be nudged, then nudged again.

When I married Ethan, I learned a second truth: marriage is two people building a life with both sets of ghosts standing beside them. Some ghosts arrive with casseroles. Some let themselves in with a garage code.

Ethan’s parents, Linda and Frank, are the casserole type. He grew up in central Ohio, the kind of neighborhood where the high school marching band still practices on summer evenings and every porch seems to carry a small American flag that taps against its bracket when the wind changes. When we closed on our little two-story outside Columbus, Linda and Frank contributed to the down payment. It was a generous, practical gift that said, We want you to start out sturdy. It also became a sentence that hovered above our doorway: “Be patient—they helped us buy this house.”

So when they began arriving without warning—midweek, midmorning, mid-everything—that sentence followed me from room to room like a polite but insistent chaperone. Linda would bustle in with a grocery bag and a mission. Frank would carry in a toolbox for “a few quick fixes,” the kind that multiply like rabbits. They were never unkind; they were simply present, confident that presence itself was help.

I adapted the way people adapt to a drafty window. You live with it until the wind changes. If their SUV rounded the bend of our cul-de-sac, I grabbed my tote bag and remembered an errand. Target returns. Pharmacy pickup. The post office that sells pretty stamps. I told myself I was choosing peace. Secretly, I was choosing to postpone conversations I didn’t know how to start.

Then came the afternoon I walked in early.

My dental appointment was canceled just as the noon siren at the volunteer fire station sang out over the neighborhood. I drove home humming along with the AM station that still plays Motown at lunch. The flag on our porch clicked softly against the pole. I unlocked the front door and stepped into a house that smelled faintly of lemon polish and brewed coffee—the scent of a staged open house rather than an ordinary weekday.

Ethan stood in the entryway like a kid caught sneaking a cookie before dinner. Color drained from his face. “You’re home,” he said, the words careful, like he’d stepped on a loose board and didn’t know whether to lift his foot or freeze.

I heard no chatter from the kitchen. No sports murmuring from the living room. Only the ticking of his grandmother’s brass clock on the hall table and a soft rustle ahead, the sound paper makes when it remembers it used to be a tree.

I walked forward. Ethan didn’t stop me. That was the first clue that whatever was happening wasn’t small.

Then I reached the doorway.

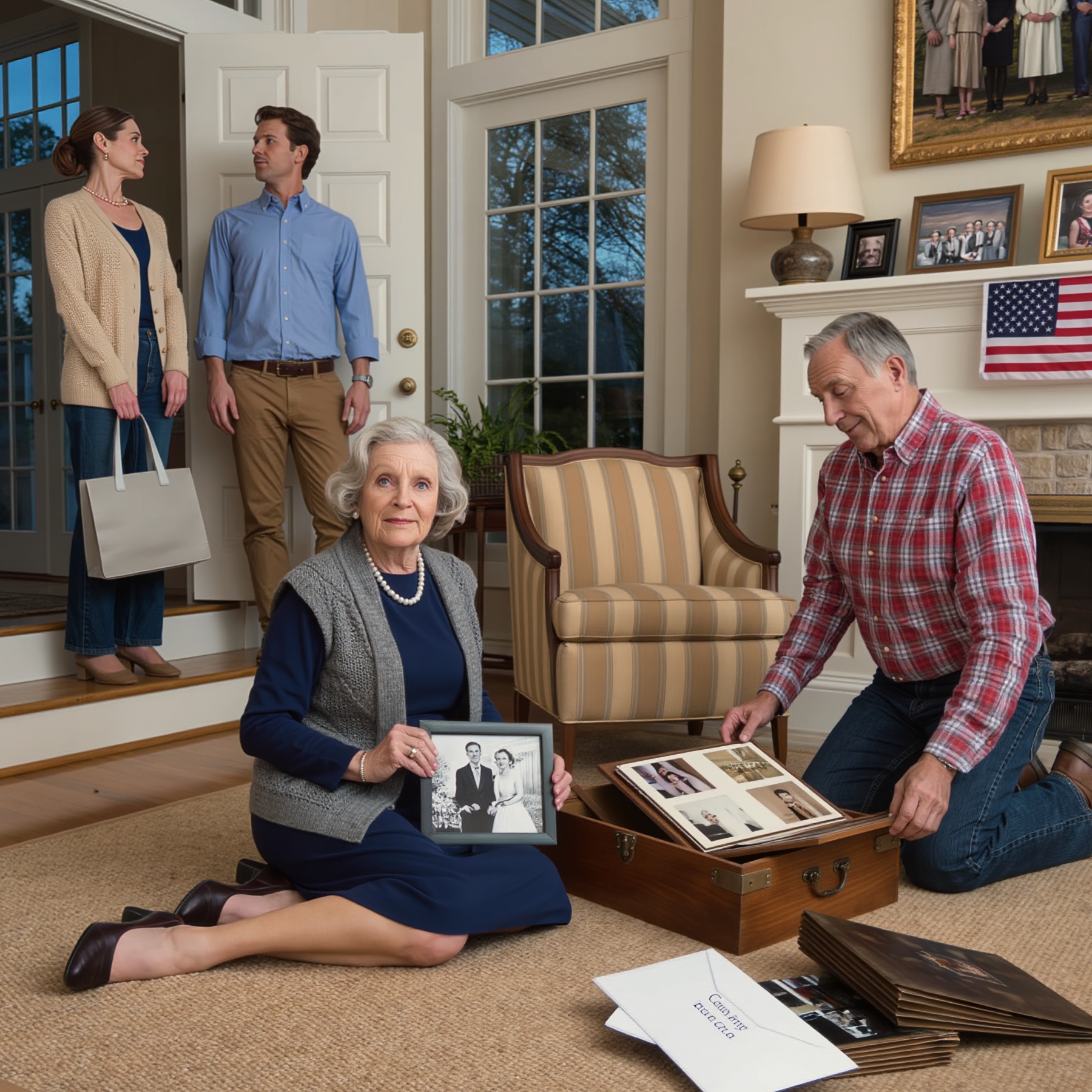

Open boxes everywhere. Loose papers. Stacks of brittle envelopes. An oil-polished wooden box with dovetailed corners. Photo albums—old ones with black pages and silver photo corners—fanned across the rug. And on the floor, cross-legged like kids at story hour, sat Linda and Frank, turning pages with the reverence of people handling something more delicate than paper.

“What’s going on?” I asked, sharper than I meant to.

Linda stood, slow and steady, as if she’d rehearsed not spooking me. “We didn’t mean to unsettle you,” she said. “We wanted to share something. We’re… passing it down.”

Ethan exhaled. “I wanted it to be a surprise,” he said. “They’ve been working on a family history project. Bringing it over piece by piece.”

I looked again. Worn photographs. Handwritten recipes stained with flour. Letters whose ink had drifted toward sepia. A tiny velvet ring box with no ring. I felt irritation rise—my space, my schedule, my living room turned into an archive—then slip as if it had found no purchase. There was nothing aggressive about it all. If anything, the room felt fragile.

I sat down because my legs told me to. Frank slid an album in front of me without a word. On the first page, a young couple grinned at the camera from a church step, confetti in their hair. His jaw looked exactly like Ethan’s. Her eyes were Linda’s before life taught them to measure.

“Your grandparents,” Linda said. “This was Cleveland, 1958. He had a Studebaker that didn’t always start. She taught second grade and could make a dress out of nothing.”

We spent the rest of the afternoon on the floor. Linda told stories that turned into other stories the way creeks flow into rivers. Frank added details—what car someone drove, what song was on the radio the first time he met Linda’s father, which uncle always carved the turkey. Ethan pointed out a photo of himself as a toddler standing on a picnic table in red overalls, arms thrown wide, as if the world started right there.

My frustration dissolved into something else—curiosity, I think, and a small, quiet ache. I had met Ethan’s family, of course. I knew the current map. But this was the terrain underneath: the hills and valleys that shaped the present. The people who dreamed and worked and made decisions that rippled forward to us. It felt like hearing the prequel to a favorite book and realizing the first chapter started years earlier than you thought.

That evening, after we’d boxed things back up and wiped the coffee rings from the table, Linda paused at the door. “We should have asked before bringing it over,” she said. “I got excited and forgot that our excitement lives in your space.”

Frank pulled a small envelope from his shirt pocket. “One more thing,” he said. “For later. No rush.” He placed it on the hall table and patted it like it was a living thing that might startle if touched too hard.

After they left, Ethan and I stood in the soft Ohio quiet that settles after sunset, when the neighborhood seems to sigh at the same time. The envelope sat between us like a doorbell waiting to be pressed.

“You want to open it?” he asked.

“Together,” I said.

Inside was a letter written in his grandmother’s loopy hand, dated the year Ethan was born. It was addressed, in a way that made my throat tighten, “To the one who loves my boy.” She had imagined me before I existed.

She wrote about her kitchen windowsill and the way the light hit the sink at 4:00 p.m. in the fall. She wrote about how she hoped we would build a house where people felt welcome and safe. At the bottom, she had clipped a small newspaper photo from her childhood home in Pennsylvania—a house that had long since been sold—and wrote, “What lasts isn’t wood. It’s the way a door is opened.”

By the time I finished, tears had gathered without my permission. I looked up at Ethan, who looked both like a confident grown man and a kid trying to hide that he’d cried during a Disney movie.

“I didn’t know about the letter,” he said. “Mom must have saved it for this moment.”

We washed the dinner dishes and went to bed feeling like the house itself had stretched a little to fit new history inside. And yet, sometime after midnight, as the clock in the hall chimed once, a nagging thought shuffled out from under the bed like dust bunnies: This was lovely, yes. But it didn’t change the daily reality that people were walking in and out of our home as if courtesy were up for debate.

The next morning, I resolved to do the grown-up thing I’d been sidestepping: ask for what I needed.

I called Linda. “Can we have dinner here Friday?” I asked. “Just the four of us. I want to hear more stories. And there’s something I’d like to talk about too.”

She agreed instantly. “I’ll bring dessert,” she said. “Your choice—apple crisp or the chocolate sheet cake that cures almost everything.”

“Surprise me,” I said, and meant it.

Friday came with that Ohio mix of sun and cloud that keeps you guessing. I grocery-shopped early, put the good napkins on the table, moved the old albums to the sideboard for easy reach, and set out a small plate of cheddar and crackers. Around five, the storm clouds slid away and a cool brightness filled the rooms. The flag on our porch lifted twice like a nod.

They arrived at six, knocked first, then stepped in when Ethan opened the door. Small progress, I told myself. Frank carried a pizza stone—his contribution to our “build-your-own” experiment. Linda brought the sheet cake, the good kind with frosting that goes on while the cake is warm and glossy.

We ate. We told stories. Then I did the terrifying thing: I named the tension.

“I love that you want to share all this with us,” I said, and gestured toward the albums. “It means more than I can say. And I need something in return.”

Linda folded her hands. Frank set down his fork. Ethan looked at me with quiet encouragement. I realized I was not alone on this conversation island; he was standing right beside me.

“I need our home to be a place where we know who’s coming and when,” I said. “Texts before visits. Knock before entering. The garage code saved for emergencies. I need to be able to plan a nap or a messy kitchen without feeling like I’ve failed a pop quiz.”

For a second, no one spoke. Then Frank nodded as if I’d finally described a measurement he could work with. “That’s fair,” he said. “We got carried away. I sometimes treat helping like a job site. But this isn’t a job site. It’s your home.”

Linda’s eyes filled. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I thought we were folding ourselves in to make your days lighter. I didn’t consider that our folding might crease in the wrong places.”

Ethan reached for my hand under the table. A knot I hadn’t realized I’d been carrying loosened in a way that felt like mercy.

“Thank you,” I said.

Frank cleared his throat. “I brought something else,” he said. “I was going to wait until next month, but maybe now is smarter.” He slid a folder across the table. Inside were neat pages—copies of copies, a stack of receipts from the closing five years ago, and on top, a document with the tidy, official language of county offices. A quitclaim deed. It transferred any interest Linda and Frank might have held or believed they held—whether because of the down payment or a badly worded conversation at the time—to Ethan and me alone.

“I wasn’t sure if we needed this,” he said. “But I wanted it to be unambiguously yours. We helped you into the house. We don’t want any invisible strings keeping you from settling fully in it.”

Linda nodded, hand on Frank’s forearm. “You’re our people,” she said softly. “We want you to feel safe. Not managed.”

You know those moments when a house seems to breathe? Warm air rises, a subtle current moves from room to room, the structure itself looks like it sits down. That’s what happened then, as if our home had overheard a conversation it had needed us to have.

We signed the deed with our favorite pen—the one that writes like a good violin sings—and Frank said he’d take it to the Recorder’s Office on Monday. Then we ate warm sheet cake and talked about the picture of Ethan’s grandparents standing in front of their tiny first apartment above a hardware store, holding a single saucepan like it was a trophy.

Around nine, while coffee perked and conversation drifted toward football schedules and whether the maple out front needed a trim, Linda reached into her purse and pulled out an envelope tied with a green ribbon. “From Nora,” she said.

“Nora?” I asked.

“My grandmother,” she said. “Your letter writer.” She smiled. “I found another note tucked behind the photo we showed you. I think she meant it to be discovered in layers.”

Inside the envelope was a recipe written on an index card in the same looping hand: cinnamon rolls, the kind you bake on a snowy morning. Below the list, Nora had written, “To be made when there is something worth celebrating, even if you have to look for the reason. Warm bread makes people remember they are loved.”

We decided to celebrate on Sunday. For the first time in months, I didn’t check the street for their SUV. I texted them the time. They texted back a thumbs-up and a little bread emoji. We fell into something that felt like a promise: we can write our norms on purpose.

I slept better that night than I had in a long while.

—

Sunday morning arrived with a crisp blue sky and the sound of an early church bell drifting from the brick steeple three blocks over. I measured flour. Ethan warmed milk and melted butter in a saucepan that used to belong to his grandmother. We kneaded the dough until it felt like a pillow you could trust with a secret. When the dough rose, we rolled it out and spread on the cinnamon-brown sugar filling, then sliced the spirals and tucked them into a buttered pan. The house smelled like generosity.

Linda and Frank knocked right at ten. They carried a jar of Nora’s apricot jam and a small, framed photograph of a sunlit kitchen with curtains that looked like they had been sewn out of a summer dress. “Nora’s window,” Linda said. “We thought it should live near your window now.”

We ate cinnamon rolls at the table with the good napkins and the everyday plates because one thing I’ve learned is that everyday plates make good days feel honest. We told more stories. We planned a family history night once a month, with texts and menu assignments and a clear ending time. Small structures that leave room for affection to roam have a way of keeping the big monsters out.

Around lunchtime, while the men debated whether the Browns would ever make it all the way, Linda opened one of the boxes they’d left with us and pulled out a stack of letters bound in twine. “There’s one more piece to tell you,” she said, meeting my eyes. “And this part belongs to you as much as it belongs to us.”

The letters were from Nora to her sister, written during a year when her father was ill and money was thinner than paper. In them, Nora described selling her childhood home and moving into that small apartment above the hardware store. She mentioned a tin box where she saved a little from every paycheck—“for the one who loves my boy,” she wrote again—because she wanted Ethan’s mother, and later me, to begin a home without the fear she had known. The down payment Linda and Frank gave us had started in that tin box decades ago. What they had been passing down wasn’t control; it was relief.

I told them it felt like standing in a stream and seeing how far back the water flows. They smiled at that.

By afternoon, the sun shifted and the house glowed in the way houses do when they approve of how a day has been spent. Before they left, we stood by the front door, and Linda said, “We’ll text before we come. Every time. Even when we think it’s ‘just a minute.’ If we forget, we’ll turn around and try again.”

It became our family joke and our boundary at once: “Turn around and try again.” It was hard the first time Linda found herself in the driveway with a bag of strawberries from the farmers market and realized she hadn’t texted. She looked up at our porch, smiled, and drove away. Ten minutes later my phone buzzed. “Strawberries?” the text said. I replied, “Yes, please. Fifteen minutes?” She came back at precisely fifteen minutes. We both felt like we’d won something that didn’t require a trophy.

Over the next few months, our house filled—in a measured, gentle way—with the family archive. Not as a flood, but as a curated stream. We bought soft cotton gloves for turning pages. Ethan cataloged photos on the dining room table with a little scanner from the library. Frank built a shallow drawer for the sideboard that fit the albums perfectly, finished in a warm stain that matched the table. Linda and I set up a recipe project, testing old cards and converting measurements written in “pinch” and “teacup” into something our future kids might use without guessing.

We also wrote down our household “constitution” on a piece of printer paper and stuck it on the fridge with a magnet shaped like Ohio:

Text before visits.

Knock even if the door is unlocked.

The garage code is for emergencies.

No “fixing” without asking.

Ask how we can help; don’t assume.

We end evenings at a time we all name.

We say thank you and mean it.

We all signed it like we were founding a tiny, benevolent nation. It sounds silly typed out. It did not feel silly. It felt like everyone getting a seat and a say at the table we were choosing to share.

There were missteps. There always are. One Saturday afternoon, Frank replaced a wobbly chair rung without mentioning it first because, in his mind, the chair had asked him for help. Ethan saw the clamp and the wood glue and said, gently, “Dad, remember the fridge?” Frank winced, apologized, and the next week brought over his tools and asked me if there was anything I’d like to tackle together. We fixed a squeaky hinge on the back door while he told me about the first house he and Linda bought—how the faucet leaked and they took turns catching the drips in a Tupperware bowl until payday.

I began to understand what this project was doing to me. It was widening my heart’s hallway. Not so wide that anyone could barrel through, but wide enough to let history walk beside me without bumping my shoulders.

Autumn came. The maples on our street set themselves on fire the way Ohio trees do when summer finally gives up. On a Saturday with air so crisp you could fold it, we hosted “Archive Night.” Ethan roasted a chicken. I made Nora’s cinnamon rolls as a savory experiment with herbs. Linda brought a pan of the sheet cake because you don’t mess with perfection. Frank arrived with a narrow box he had made in his workshop and placed it on the table without fanfare.

Inside lay a small, folded flag from Nora’s brother’s service, worn soft at the edges, and a typed note explaining its history. Underneath that, a photograph of a Fourth of July parade from the early 1960s—kids with sparklers, a marching band in exact rows, men in short sleeves carrying lemonade. I held the photo and thought about how many hands have lifted flags for reasons that are, at their core, the same: to say “here is where we belong, and here is whom we belong to.”

“Let’s give something back,” I said, surprising myself. “Not the artifacts—they’re ours to keep safe—but the stories. The library downtown has a local history room. What if we donated digital copies and a few framed prints? We could host a presentation—tell Nora’s story, and how her small savings became a down payment that crossed generations.”

Linda pressed her napkin to her eyes. “She would have loved that,” she whispered.

So we did. We set a date in late November, when people are already thinking about the families who made them possible. The librarian, a kind woman who wore cardigans with tiny embroidered pinecones, helped us design a little exhibit. Ethan stood at the front of a modest meeting room and explained how one family’s savings became another family’s stability, how gifts are cleanest when they’re given without strings, how boundaries actually make generosity bigger because they keep it from spilling out and soaking everything.

I stood next to him and said the part that felt like justice: “For a while, I thought being grateful meant staying quiet. It doesn’t. Gratitude breathes best when the windows are cracked and everyone knows who holds the keys.”

People nodded. A teenager in the second row came up afterward and asked if he could interview us for his school project about “ordinary American stories.” I told him that ordinary is often where the best things hide.

At Thanksgiving, we set the table with Nora’s recipe cards standing in little frames down the center like family in paper form. We didn’t cook everything. We cooked what we do well, and Linda filled in the rest. After dinner, we took a walk around the block, the way Midwestern families do when they need to justify a second slice of pie. The air smelled like leaves and chimney smoke. The porch flags rested in the stillness like their work for the day was done.

On Christmas Eve, the four of us sat in our living room, now measured not by surprises but by choices. Gifts were simple: I had their cinnamon-roll recipe professionally transcribed and printed in Nora’s handwriting as if she had written it yesterday; Frank gave us a small wooden box with a false bottom “for secrets you want to keep safe from dust”; Linda gave me a delicate gold necklace with a tiny locket that held a scrap of Nora’s handwriting—the word home, cut carefully from an extra copy. Ethan gave his parents a framed print of the letter “To the one who loves my boy,” with the last line highlighted: What lasts isn’t wood. It’s the way a door is opened.

The new year arrived the way Ohio new years do—gray, honest, unglamorous and full of promises you’re free to keep at your own pace. We kept meeting once a month. We kept texting before we came. We kept telling the truth kindly and not saving resentments like coupons we’d use later.

Spring brought the kind of Saturday that makes you throw open every window you own. Linda and I took the archive project to the next step. We recorded her telling stories while we cooked, the microphone perched on the flour tin like a tiny guest. Her voice came through strong and warm as she narrated the exact crack the crust should make when a loaf is ready, the reason her father always tapped the thermostat twice after turning it down (“habit and hope,” she said), the list of phrases Nora used when she wanted you to know she was listening (“I hear you,” “Tell me more,” “Let’s make tea”).

We saved those recordings on a hard drive and backed them up three different ways. We labeled everything. We made a binder that a future child could open and understand: here is where you came from; here are the recipes and letters and stories that held your people together when money didn’t; here is the little flag from a parade that once moved down a street that still exists.

By summer, news of the library presentation had wandered farther than we expected. The local paper called, then a regional magazine that likes to run “real life” features with photographs of ordinary families at kitchen tables. We agreed only if they didn’t turn it into a lesson with sharp edges. The writer listened. The photographer asked us to gather on the porch. He angled the shot so the flag hung in the upper corner and the maple leaves framed us green. When the article ran, the headline read: “A House Full of Stories, and the Boundaries That Keep Them Sweet.”

In August, Ethan and I celebrated our anniversary with a long weekend at a little place on Lake Erie that smelled like sunscreen and fried dough. We talked about the next ten years the way you talk about a road trip—half plan, half hope. We decided we wanted to try for a baby, and if that wasn’t part of our path, we’d chart another one with the same kind of faithfulness people use to drive through fog.

On the last night, we sat on a bench while the sky did that miraculous Ohio thing where it throws pink like confetti, then sets the confetti on fire. Ethan took my hand. “I didn’t realize how tense I was until it left,” he said, not needing to specify what “it” was.

“I didn’t realize how hungry I was,” I said, “for both history and privacy at the same time.”

We returned home to find a small package on our porch with a card: “For the next chapter, whenever it begins.” Inside was a baby blanket Linda had knit in a soft gray. Not a push. Not a hint. Just a possibility made tactile. My eyes stung in the best way.

In October, the Browns did what the Browns do, and Frank continued to be loyal anyway. We hosted an autumn dinner and invited the neighbors who wave from riding mowers, because community is also inheritance. I made a big pot of beef stew from a recipe that started as a note Nora had scribbled—“brown the meat like you mean it”—and turned into a family favorite. Linda brought apple crisp so fragrant the entire block could smell it.

Near the end of the evening, as the sky bruised purple and kids practiced cartwheels on our lawn, our neighbor Mrs. Alvarez leaned over and whispered, “I wish my in-laws had learned this.” She gestured toward the fridge where our little “constitution” still hung. “You give me hope for my daughter. Maybe she and her future husband can start their house with a list, not just a mortgage.”

“We started with a mortgage and a mess,” I said, “then we made a list.” We laughed. She asked for a copy; I handed her one from the printer drawer because we keep spares now, like recipes.

Winter returned. This time, the gray felt healthy, like a blank page instead of a curtain. On a snow-quiet afternoon in January, we got a call from the library. The exhibit had become popular. People were leaving sticky notes on a board at the end: “My grandmother kept recipes in a shoe box”; “We never talked about boundaries but needed to”; “I called my mother-in-law today just to tell her a story.” The librarian asked if we’d like to host a workshop: “Family Histories and House Rules.”

We said yes. At the workshop, we didn’t preach. We told a story. We showed our binder. I went first, because I know what it feels like to be the one who seems to be complaining while someone else is offering help. “You can be grateful and still ask for space,” I said. “If love is a room, boundaries are the windows. They let the good air in.”

After, a woman my mother’s age waited until the room emptied and then took my hands. “My daughter married last year,” she said. “I thought the way to love her was to be there all the time. She asked me to slow down. I didn’t hear it until tonight.” She smiled through a glimmer of tears. “I’m going to text before I stop by. And I’m going to bring her our family albums in a box, not scatter them on her coffee table.”

I hugged her. I don’t know which one of us needed it more.

The months swung around again. On a warm June evening, I made iced tea and set it on the porch. The flag lifted once, then lay quiet. Ethan came out with the mail, flipped through the envelopes, and paused. “From the county,” he said. Inside was the recorded quitclaim deed, officially stamped and returned. I framed the first page and hung it on the wall in the hallway that leads to the living room. Not because paper defines love, but because clarity honors it.

A week later, a small plus sign appeared on a white stick in our bathroom. I carried it to the kitchen like it might float if I didn’t hold it carefully. Ethan set it on the counter next to the cinnamon and flour, as if the baby could hear the room where its first holidays would be baked.

We waited until the doctor confirmed, then called Linda and Frank. Before we said the words, Linda said, “I knew you were going to call. My heart’s been restless all day.” When we told them about the baby, her hands flew to her mouth and Frank said, “Well, we’ll text before we come over to cheer.”

They did. They texted. They brought soup and left it on the porch with a photo of it so we knew it was there. They asked what we needed and listened when the answer was “nothing but a nap.” They offered to assemble the crib and then waited for us to say yes. When we said yes, Frank arrived with his toolbox and knocked twice—once with his knuckles, once with his wedding ring because he likes the sound—and didn’t step in until Ethan opened the door.

Our daughter was born on a rainy afternoon in early spring, when the maples were the color of new pennies. We named her Nora. When we brought her home, the house felt brand new and also exactly itself. Linda stood in the doorway and asked, “May we come in?” She didn’t even make it to the couch before tears streaked her face. Frank rocked Nora like someone who knows that the rhythm is more important than the song.

We hung the little framed word home over the rocking chair and tucked the recipes into a shelf where I could reach them with one hand. On the first Sunday after we caught our breath, Linda and I baked cinnamon rolls with Nora sleeping in a sling against my chest, her breath like the tiniest metronome. We ate them warm and imagined the day she’d stand on a stool and sprinkle the sugar herself.

Not every day is soft. Some mornings Ethan and I snap at each other about laundry or time or the illusion of control. Some afternoons we forget the list on the fridge and answer the door with hair wild and patience thinner than batter. But most days we remember. And when we forget, we turn around and try again.

A year after the first archive night, we hosted another library event—this time with a row of strollers near the door and a plate of cut cinnamon rolls next to the sign-in sheet because the best stories are easier to hear when people aren’t hungry. We told the room what we have learned: that families are made of memory and choice; that generosity without boundaries can feel like weather and generosity with boundaries feels like shelter; that justice in a home looks like everyone’s dignity intact.

After the Q&A, a man who had sat in the back with his arms folded stood and spoke. “I came here ready to argue,” he said. “My son says I’m overbearing. I call it being helpful.” He paused, breathed. “I’m going to create a list. I’m going to ask what helps.”

On the way out, he stopped at our table. “Thank you for not making me feel like the villain,” he whispered.

“You’re not,” I said. “You’re part of the story.”

We walked home as the sun went down—Ethan pushing the stroller, Nora kicking her feet, Linda and Frank just behind us. I looked back at them and thought about where we had started: the surprise visits, the garage code, the ache of feeling outnumbered by other people’s good intentions. And I thought about where we were now: a family that sets a table before it sets a schedule, a house where albums live in a drawer built by a grandfather who prefers to be asked, a kitchen that smells like cinnamon and patience.

The quiet truth is that nothing magical swooped in to fix us. We made a choice, then another, then a hundred more, to be the kind of people who give one another both history and room. We chose to be grateful in a way that doesn’t erase our needs. We wrote the rules down. We practiced until they felt less like rules and more like rhythm.

On Nora’s first birthday, we invited neighbors and family and anyone whose life intersects with ours in ways that make the days richer. We set up a small display on the sideboard: her photo next to Nora-the-elder’s letter, the cinnamon-roll recipe in a little frame, the tiny velvet ring box with a note that said, “Empty so far—waiting for whatever love decides.” People drifted over and read, then came back to the table and told stories of their own. Mrs. Alvarez brought flan. The teenager from the library, now taller and newly confident, filmed a few minutes for a follow-up project.

Just before we served cake, Linda cleared her throat. “We have something for you,” she said, and handed me a wrapped package. Inside was the photograph of Nora-the-elder’s kitchen window, newly reframed, with a small piece of the original curtain carefully stitched behind the glass in a neat square. “A window within a window,” Linda said. “Because you opened yours for us, and we want to keep opening ours for you.”

I placed it on the mantel next to a vase of daisies and felt a tide come in, steady and full and exactly right.

After everyone left and the dishwasher thrummed and the house settled into its evening posture, Ethan and I stood in the living room and looked at what we had. Not the furniture or the framed papers. The feeling. It was as if the walls themselves remembered that homes are built from more than lumber and paint. They are built from the way people pause at the doorway and ask if now is a good time, from the way a grandmother writes a letter to a woman she has not met, from the way a couple sits on the floor together and decides that gratitude and boundaries are not opponents but dance partners.

I picked up our sleeping daughter and walked her down the hall past the framed quitclaim deed, past the bookshelf that now held a row of albums, past the kitchen where the last of the cinnamon scent lingered. I whispered the only benediction that felt true.

“Welcome home,” I told her. “This is your story too. And here, justice looks like kindness with good manners.”

The flag outside ticked once against its pole. Somewhere a neighbor laughed. The clock in the hall, steady as always, marked the moment with a soft, unassuming click, and our house—ours—breathed.

News

My son demanded that I cover his wife’s $300,000 debt, saying I needed to transfer the money by tomorrow and stressing “no delays,” but I simply nodded calmly and started packing my suitcase; a few hours later, I was on a plane, leaving behind the house that had once been in my name. When he came back to my place looking for the money, all he found was a locked door and an envelope that left him stunned.

I needed the money yesterday, my son demanded, handing me his wife’s $300,000 debt as if it were a simple…

While I was quietly on vacation in Colorado, my daughter sold the penthouse in my name to plug her husband’s money problems, laughed that I’d have nowhere to live now, and never once suspected that the “little place” they rushed to sell was actually the least important property in the quiet, carefully planned portfolio I’d been building for years.

You know, they say you never really know someone until they show you who they truly are. I learned that…

After my ex-husband told me to leave his house with nothing after the divorce, I pulled out an old bank card my late father had left behind and tried to use it at a small U.S. branch, and the way the tellers suddenly rushed to call their manager, whispering, “Look at the account holder’s name,” exposed a family secret I was never meant to find out.

My husband put me out and kept all my assets just to hand them over to his mistress. All I…

My Twin Sister Showed Up at My Door in a Small American Town Looking Drained and Hiding Behind Long Sleeves, and When I Realized Her Husband’s Behavior Was Quietly Breaking Her Spirit, We Swapped Places So I Could Smile, Take Notes, Work With a Lawyer, and Turn His Picture-Perfect Marriage Into the Wake-Up Call He Never Saw Coming.

My twin sister came to visit me at the hospital, covered in bruises all over her body. Realizing she was…

I went bankrupt and my husband decided to leave, and at 53 I went to a plasma donation center just to receive $40 to get by, but after seeing the results the nurse called in a doctor and said I had the extremely rare RH-Null blood type that only a few dozen people in the world have, which opened the door to an unexpected financial support offer from a billionaire family in Switzerland.

The receptionist handed me a clipboard with a stack of forms attached to it. Her practiced smile never reached her…

At 2:47 a.m., my grandson called me from the police station, sobbing that his father believed every word his stepmother said accusing him of causing her to fall, yet when I walked in the duty officer suddenly stood rigid, his face draining of color as he whispered, “I’m sorry, I didn’t recognize you,” and from that moment our family was dragged into a confrontation with the truth.

My grandson called me late in the night. “Grandma, I’m at the police station. My stepmother hit me, but she’s…

End of content

No more pages to load