The morning after Christmas has a silence that isn’t quiet. It sits in the windshield and the floorboards, in the seams of a winter coat, in the pause between the heater’s clicks. My badge was still in the tote on the floor; the smell of ER coffee clung to my hands like iodine. My husband kept his eyes on the plowed street and the line of salt along the curb. We didn’t speak because we didn’t have to. A plan, once settled, doesn’t need commentary.

I had not yelled. I had not driven back across town to stage a performance on a porch. That isn’t how you change outcomes; that’s how you feed the story other people will tell about you. I had gone to work, done my compressions, called my time of death, charted what needed charting. I had come home at 11:45 p.m., seen my daughter’s boots by the door, felt the old coil form in my chest, and asked gentle questions until the shape of the night became what it was: an answer I would not live with.

“Let’s just leave it if no one comes,” my husband said now, one hand soft on the wheel. He didn’t mean the envelope wouldn’t land; he meant I didn’t need a confrontation to make it real. He was right.

We turned onto the cul-de-sac where the white colonial sits—black shutters, wreath still pinned to the glass, a tiny American flag leftover from the Memorial Day parade tucked in the porch planter because my mother never removes anything she thinks proves a point. My house. The one I bought seven years ago, deed in my name. The one I let my parents live in rent-free because I believed you can be both generous and boundaried if you document what you’re doing. I was wrong about the second part. You can be generous. But generosity without enforcement isn’t a boundary; it’s an invitation to be erased.

There were still extra cars in the driveway. I recognized Janelle’s hatchback by the chipped bumper sticker she refused to scrape off. Another sedan I didn’t know sat crooked, the way relatives park when they think rules are suggestions.

I took the envelope from my coat pocket. Plain white. No underlines. No exclamation points. A document doesn’t need flair to carry the weight of an answer.

We rang the bell. We waited. No footsteps. No motion. I slid the envelope into the doorframe, above the drift where the snow would spit and melt. I turned. The hinge sighed.

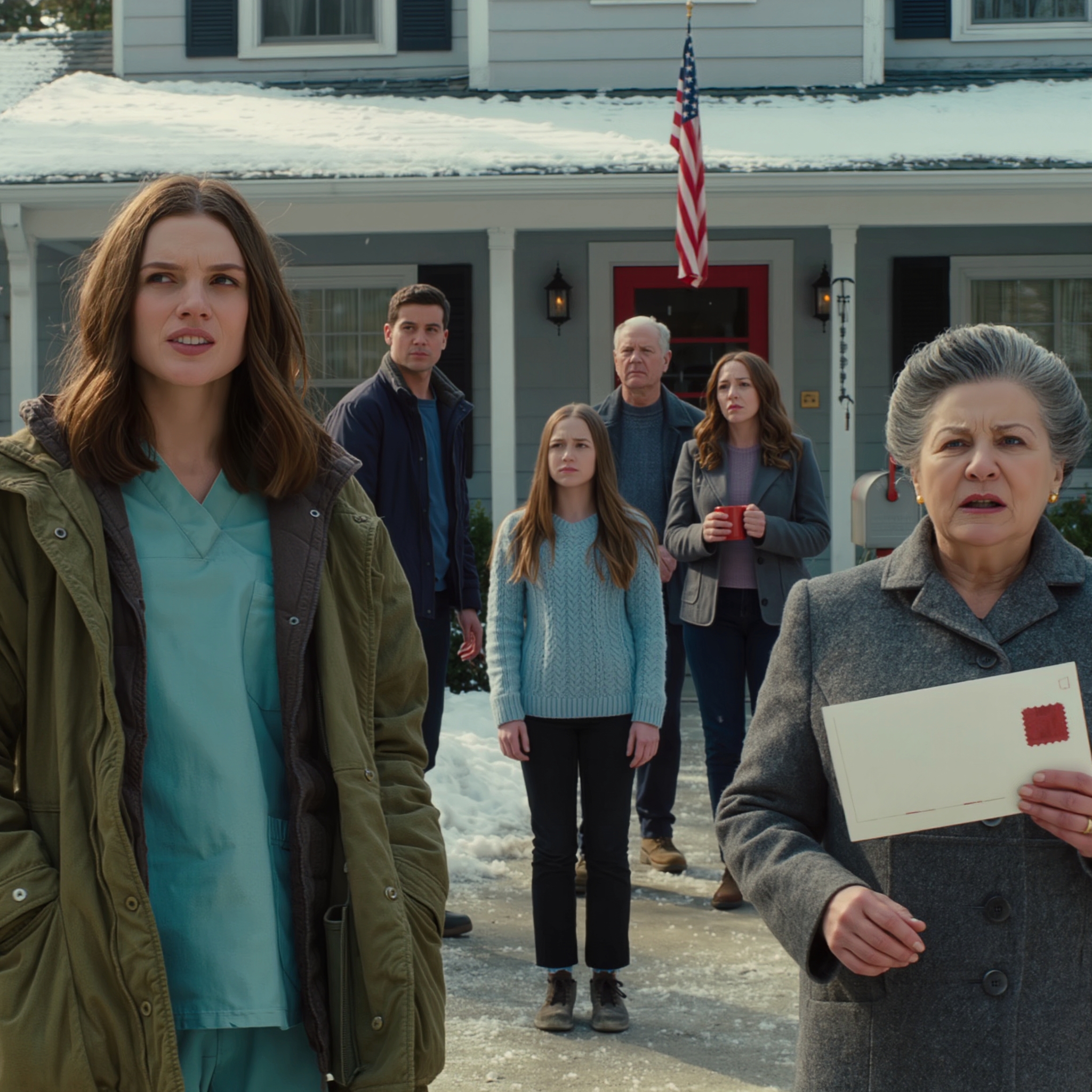

My mother stepped out in her fuzzy robe—navy with those little white stars she bragged about getting ninety percent off. She saw us. Then she saw the envelope. She bent, picked it up, and opened it right there in the cold. I watched the color in her face go from post-holiday pink to the gray of hospital linoleum.

“Frank,” she said, and her voice did the thing voices do when the outcome is already set. My father appeared behind her in yesterday’s sweater with his glasses in his hand, ready to perform concern. Janelle drifted into the doorway, clutching a mug like this was the trailer for a cozy family movie.

“What is it?” she asked.

I didn’t answer. That’s what the paper was for.

The paper said the license to occupy was revoked. It said the owner of record—me—had served notice to terminate permissive use. It cited the recorded instrument on file with the county. It spelled out the date by which the property must be returned vacant and the next step if the deadline was ignored. It used boring, precise American English that left no room for misunderstanding. It included Abby’s name exactly where it belonged: as the minor child whose safety and access had been considered and violated.

My mother’s hand shook. She looked up at me over the edge of the letter like I had reached into her pocket and removed a story she needed more than breath.

“You wouldn’t,” she tried.

“I did,” I said.

It would be cleaner to tell you she apologized then, or that she remembered Abby’s face on the porch, the sweater my mother had once said she liked, the overnight bag my girl had zipped carefully because she believed in tradition. It would be cleaner to tell you my mother felt what a decent person feels when they understand the shape of what they’ve done. But we do not get the clean version of people who have practiced the messy one for decades. She screamed. She summoned my father by his name like an alarm. She pointed the letter at me as if it were a weapon, and when the syllables ran out of her throat, she landed on the only truth she could bear:

“You’re ungrateful.”

We left. The calls started before our tires stopped throwing salt. I ignored the first, then the second, then the sixth. When I finally answered, my mother didn’t ask about Abby. She didn’t ask what had happened. She told me I had lost my mind. My father shouted that I was “no daughter” if I followed through. Janelle texted that I was ruining my reputation and that my “career” wouldn’t survive this. As if my patients care where my parents live or whether I finally enforced a boundary I documented the year the mortgage began.

Two mornings later, my mother stood on my porch in the robe with the stars and ripped the first letter down the middle like a coupon. Theatrics are oxygen for people who’ve never had a decision stick to them. I watched the halves droop in her hand like wet sails, then fall to the doormat.

“Done,” she said. “Now pay for Lily’s science camp and stop this.”

A better person might have laughed. I didn’t. I was tired. I had been awake for thirty hours out of thirty-six. I had a sixteen-year-old to feed who had eaten a single slice of cold toast and half a banana for Christmas dinner because twenty-eight people had been fed at a table where there was “no room” for her. I was unknotting the coil in my chest by choosing a path that did not require explanation.

The second letter came by certified mail and process server. It had a green return receipt and an affidavit of service. It was not rippable. Neither was the courthouse docket my father’s name would appear on ninety days later when his answer failed to materialize and the word “default” attached itself to a life he thought he could shout his way through.

Let me go back. Let me tell you why the quiet choice was the only one left.

When I was six, I found a dead bird and wanted to know how its pieces made flight, how muscle married to bone and feather translated to sky. I asked to open it and was told I was wrong for wanting to understand the world. When I was twelve, my father joked I was too smart to be his, then said he always wondered. When I was seventeen, I got the scholarship and there was no cake, only a conversation about how men don’t like women who act smarter than them. When I was twenty-six, I finished my second residency and bought a microscope just because I promised a six-year-old version of me I would. When I was thirty-two, I bought a house for two people who had never learned what gratitude looks like in a ledger.

Janelle—the golden child by consensus and self-narration—could always turn a room with a story. She was excellent at failing in public and making it someone else’s fault. When Lily got into a STEM camp three months before Christmas, the calls came like weather reports: “It’s good for her future”; “You, of all people, should know what this means.” I said no. Politely. Once. Then I said it again. The argument matured in a way only arguments with people who never pay bills can: I was accused of jealousy for not underwriting a story where I was meant to be the ATM with a stethoscope.

We arrived at Christmas from that. We arrived at my daughter on our couch from a history that had documented itself in a thousand disposable moments. People like to make the big scene into the beginning. It isn’t. It’s the ledger catching up.

The first hearing on the unlawful detainer was exactly what court is: fluorescent light, a flag in the corner, the seal of the state behind a judge who has seventy-six cases before lunch. My father sat next to my mother at the defendant’s table in a jacket he saves for weddings and funerals. Janelle wore a blouse that said she was on the side of the story that wins. I sat by my attorney with a folder of copies: mortgage statements, utilities I’d covered, certified mail receipts, the written license to occupy I’d made them sign the day I handed them the keys and a cake.

The judge asked if there was an agreement. My father said there was an understanding. The judge asked if there was rent. I said no, it was permissive use. The judge asked if notice had been served properly. My attorney placed the green return receipt and the affidavit of service on the table like cards no one could trump.

My mother tried to speak. The judge lifted a hand. “Ma’am, I’ll hear from respondent’s counsel first.”

Their counsel, a man I’d never met, stared at a file as if the papers inside might produce an argument if he looked hard enough. He requested a continuance because he was retained last night. The judge gave them two weeks and asked me if I objected. I did not. Justice does not need speed to be justice; it needs a record.

Two weeks later, we returned. My father had words now—big ones about loyalty and intention. My mother had silence she deployed like a weapon. Janelle had a glare for me she perfected in adolescence. The judge took fifteen minutes to review what he had read two weeks earlier. He ruled exactly the way statutes rule when they meet facts: possession to the plaintiff, stay of execution ten days, costs as allowed by law. He slid a form across the bench to the clerk and asked the next case to approach. It was over.

“Over” does not feel like victory when the people losing are your parents. It feels like standing on the far side of a bridge you built and realizing they never intended to cross it with you. It feels like grief, but clean. There is a difference between the grief you carry because the world is cruel and the grief you choose because you will not participate in cruelty. I chose the second.

The sheriff’s civil unit posted the notice on the door with blue tape. My mother took a photo as if Photoshop could edit procedure. My father muttered something into the porch that contained my name and a word he pretends he doesn’t say. Janelle posted nothing and texted me everything. Ten days later, the lockout occurred. I was not there. People will tell you it is unfeeling to remove your parents from a house. Those people did not watch their sixteen-year-old eat cold toast because twenty-eight chairs were occupied by everyone except her.

The buyer closed the following week. Vacant possession delivered. I did not squeeze the sale; I priced it fairly because endings should not be profit centers; they should be exits that let you breathe. The proceeds went where they needed to go: Abby’s 529 plan first, then a fund I named in my head before I named it on paper—Room at the Table—designed to buy folding chairs and full plates for kids who arrive where they belong and are told there isn’t space. It started small. It did not stay small.

Janelle took my parents in after the lockout because she is good at cosplaying the better daughter when there’s a camera, even if the camera is the one in her mind. It lasted three weeks. Her texts to me during those twenty-one days read like a soundtrack for choices catching up: “They hate sharing a bathroom,” “Mom says your nephew is loud on purpose,” “Dad changed the thermostat and says it’s his house.” When she arrived at my door one Tuesday morning, hair frizzed, eyes rimmed red, I knew. “I can’t do it,” she said. It wasn’t a confession. It was a weather report finally aligned with the actual sky.

“They need a rental,” she added. “Just help with the deposit.”

“No,” I said. And the word was clear, not cruel. Boundaries are only cruel if you call a locked door violence and an open window consent.

They found a rental two neighborhoods over—a long, flat building with uneven steps and mailboxes that have seen hands and winters. Their pension covered most of it. The keyboard’s calendar included payment reminders my mother had never had to set. The wash of calls from cousins slowed when I began to answer them with PDFs: utilities paid in my name; medical bills my plan had covered; the stamped, certified notice of what had happened and when. The family who wasn’t there became suddenly neutral. Neutral, I’ve learned, is a kind of grace.

Abby healed in the ways teenagers do when you give them a story that says they matter more than anyone’s denial. We went to therapy together. We learned how to say what we felt without letting the feeling take the wheel. She picked electives that felt like light instead of obligation. She started volunteering on Saturday mornings at a community kitchen that fed anyone who showed up. “We never run out of chairs,” she said once, and I had to step into the hallway to breathe because there is a mercy in hearing your child write a better sentence than the one she was handed.

Spring arrived after a winter that felt biblical because consequences often do. My mother called less. My father texted not at all. Janelle oscillated between contrition and the conviction that this would be better if I were different. In April, Aunt Elaine knocked with a tin of cookies and a face that looked like humility. She said she hadn’t known. I told her she hadn’t asked. We drank tea we didn’t finish and made eye contact with parts of the past neither of us can edit.

There’s a myth that justice and joy cannot share a room because justice requires a kind of hardness that squeezes joy to the edges. It isn’t true. Justice clears space. Joy notices.

By the next Christmas, our house was full. Not stuffed-with-people full. Right-sized full. Abby’s friend Camila, whose parents worked in retail and always got the short end of December, came with a pie she baked at 6 a.m. because ovens don’t care about shifts. Mr. Alvarez from down the street brought his famous mac and cheese. The ER nurse who held compressions with me on that blue man’s chest and whose wife had taken their toddlers to see grandparents in Michigan sat at our table with the ease of someone not auditioning for acceptance. We had a small flag on the mantle because the kids had made construction-paper ones for a school unit and Abby insisted that every table should have room for proof that you belong.

We went around and said one true thing each. Abby said hers into the quiet like a wish that was already fulfilled. “I felt like a folding chair last year,” she said. “This year I feel like the table.”

I did not cry. I nodded. Sometimes agreement is its own kind of tear.

I would love to tell you that was the end, but endings are rarely tidy. They are rounded corners, not sharp cuts. In February, my mother left a voicemail that was not about rent or blame. It was five words: “We need to talk. Please.” “Please” was a new addition. My husband listened and said nothing. People forget that silence used well is an act of love. He trusts me to choose.

I met my parents at a coffee shop near the courthouse because I am allergic to kitchen tables where people pretend eggs and butter erase what’s on the ledger. The room had the clean light of a Midwest winter noon. A flag hung above the service counter because someone thought coffee tastes more American beneath fifty stars. My mother sat with her hands around a paper cup as if heat could confer penance. My father’s jacket was buttoned wrong again.

“I’m not here to renegotiate the past,” I began because clarity is a kindness.

“We were wrong,” my mother said, and the words hit the table like something heavy that finally remembered gravity. “We told ourselves it was logistics. It wasn’t. It was… we thought we were teaching you to be tough by making you small.” She looked at me then and at the space above my head because the easier thing would be to say this to a light fixture. “It was cruelty,” she added. “We were cruel.”

My father did not speak. He stared at the corner where the bulletin board held community announcements: lost cats, tax prep, auditions for a community theatre’s spring show. He blinked. “I don’t know how to be the kind of man who says sorry,” he said finally, the sentence tasting like metal. “But I know how to say we were wrong.”

If you are waiting for a hug here, you will be disappointed. People in stories lean across tables in slow motion and cry into each other’s hair. People in life fumble and make a plan. I told them we could try a thing called repair. Repair requires an apology, an acceptance that apologies do not erase consequence, and a form of restitution that is not a check but a change. I said Abby would not be enlisted in it. I said any contact would be through me until my daughter decided otherwise. I said the first act of repair would be a letter. Not to me. To Abby. Not asking forgiveness. A letter that named what they had done and acknowledged the harm. No excuses. No “but.” No “if.” I gave them examples because sometimes mercy looks like a template.

They wrote the letter. Abby read it at the kitchen table with her hand on the envelope like it might run away. She did not cry. She asked if she had to answer. I said no. She folded it back into the envelope and placed it in a drawer with the college brochures because both were about futures she was allowed to choose. She left the room lighter than she entered. That is the whole point.

Spring turned into a summer of heat that made asphalt shimmer. Abby took the green form from the 529 and made it real: she selected a university where she’d major in biomedical engineering because the world needs people who can build devices that turn breath and data into life. On orientation day, we stood on a campus green where a small flag waved on a pole above an information tent and a student in a polo with the school crest yelled the word “Welcome!” like he’d invented it. Abby smiled at a future and at a life where the chair with her name on it wasn’t negotiable.

The first year was hard the way first years are. There were exams and the kind of roommate drama therapy has good words for. There were calls to me that began “I’m fine, but” and ended with ordering pizza at midnight because food is control for freshmen and sometimes the best thing you can do is remind a girl that hunger is not a moral question. There were afternoons when she slept without setting an alarm and mornings when she woke before sunrise because ambition and anxiety share a wall.

At the end of that year, Abby applied for a summer internship at the hospital where I work. Not in the ER. In the biomedical lab that maintains ventilators and monitors and the little devices that beep with the rhythm of a body refusing to quit. She interviewed in a blazer we bought secondhand and tailored for ten dollars. She got the position. The first morning, she took a photo on her phone: a row of devices lined up like small white birds on a counter, the flag in the corner of the lab a blur, the caption a simple line—“Making room.”

I saved that photo. I will give it back to her on a day that matters.

By the time Abby started her second year, the Room at the Table fund had bought a thousand folding chairs and paid for two hundred meals and three prom tickets for kids whose parents love them in ways that forget how logistics work. It had also paid one deposit on one small apartment for a girl who aged out of foster care in December and refused to choose between finishing high school and a job that would drain her. It is not a large fund. It is enough. Most true things are.

Janelle called once that fall with a voice I recognized from middle school. She said she was sorry. Not for the noise; Janelle can metabolize noise like oxygen. Sorry for watching a girl stand on a porch and doing nothing louder than a shrug. She said Lily loved her chemistry class. She said she had told Lily to work for what she wants because asking other people to underwrite your future without regard for their present is how you end up with a life full of empty rooms.

We met for coffee. We did not become best friends. We did something better: we negotiated the only truce that matters—one where you don’t forget what happened and you don’t use it like a stick. She asked if she could come to Abby’s poster presentation in the spring. I said I would ask Abby. Abby said yes, but only if Janelle sat in the middle of the audience and kept her phone in her bag. Janelle laughed and promised. She kept her promise. I watched her clap, not for herself, but for a girl who built a model of a device that could make NICU nurses’ hands faster by one second. Sometimes one second is the point.

You want the part where justice pays dividends? It does. Sometimes slowly. Sometimes like August thunder.

Late that spring, my parents asked if they could sit in the auditorium when Abby gave the presentation again as part of a scholarship competition. The scholarship had a name that sounds like legacy and a committee that looks like a brochure, and a flag pinned to the curtain because people think patriotism is an accessory and forget it is a discipline. Abby said she would allow it if they sat in the back row and left without approaching her. My mother agreed. My father nodded. They came. They watched a girl they had rendered invisible on a Christmas Eve make a room listen because her hands and her mind had learned how to turn care into engineering.

She won.

The check wasn’t as big as the house proceeds, but it was money earned by merit in a room that values receipts. Abby stood on the stage with the lights making halos out of dust motes and said words I did not feed her:

“When I was sixteen, I was told there wasn’t room for me at a table. This is a reminder to everyone—including me—that if you can’t find a chair, you build one. Then you slide it in and make space for someone else.”

The room stood. It didn’t erupt. It rose like people who know what they are looking at when they see a story turn into a sentence that becomes a future. In the back, my mother sobbed in the way shame sounds when it realizes it cannot be translated into blame anymore. My father clapped as if his hands were learning a new language.

Abby walked offstage and straight into me. She didn’t cry. She said, “I’m hungry.” That’s my girl.

Our celebration was burgers and fries at a place with paper napkins and a TV showing a baseball game with the sound off. A small flag sat in a jar of lollipops near the register because it was June and someone had set it there next to a flyer for a blood drive. We ate. We watched a little boy drop ketchup on his shirt and decide not to care. We talked about nothing and everything because that’s what victory actually is: the space to be ordinary in a life you fought to make decent.

You are waiting for the part where I tell you what happened to my parents. I can tell you this much: they did not become saints. They did not morph into different humans because a judge signed a form and a sheriff changed a lock. But they started attending a thing at the community center called “Repair Conversations,” where people sit in hard chairs under fluorescent light and practice the muscle of saying, “I harmed you and I am not owed your forgiveness, but I am committed to becoming safer.” I read their sign-in sheets once because someone handed them to me to show me they were trying. I nodded and handed them back. Trying is not a medal; it is an act.

They moved to a smaller rental that has two steps my father complains about and neighbors my mother likes. They got a cat from the shelter and my mother named it Frank because humor is a way control reenters rooms through back doors. They send cards on Abby’s birthday. They are short. They say, “We are proud of you.” They do not ask for tickets or seats or credit. They are learning, in the seventh decade of their lives, a truth you and I should learn earlier: you do not get to keep what you are unwilling to care for.

Two years after the eviction, I walked Abby up the steps of her dorm for the last time as an undergrad. She handed in her final lab report and turned to me with a grin that contained every shift, every invoice, every quiet morning when the answer arrived in an envelope. She had been offered a spot in a graduate program that would let her work on devices that make breath easier for tiny lungs. She accepted. We hugged in the hallway under a bulletin board with flyers and an American flag sticker peeling at the corner.

On the drive home, the sky did that big Midwestern thing where it looks like a promise. We passed the exit to the old neighborhood and I didn’t take it. You can drive by the past. You don’t have to visit.

That night, in our kitchen with the scar on the counter where Abby once dropped a pot and cried because she thought I’d be angry and I was only relieved no one was hurt, I set two plates. My husband poured iced tea. Abby opened the window because the evening felt like a room with enough air. We ate without hurry.

“Do you ever think about that toast?” she asked, not sad, just curious.

“Yes,” I said. “But mostly I think about the pie you bake now and how you take the first slice to your neighbor because you were the girl who noticed.”

We did dishes. We watched the news without absorbing it. We turned off the lights. We went to bed in a house that doesn’t practice performance. In the morning, the mail brought a letter from the Room at the Table fund—a note from a kid who used a folding chair we’d bought to sit at a graduation party where she had not expected to be counted. She drew a flag in the corner with a blue pen and wrote, “Thank you for the seat.”

I pinned the note on the refrigerator next to a postcard of Abby’s campus and a photo of a lab bench with little white machines and a blur of a flag in the back. Justice and joy, side by side, like they belong.

I know what people think when they hear I evicted my parents. They reach for the story that makes it make sense to them because that is what stories are for. Here is the only version I recognize: I protected my child with the quietest, sharpest tool I had. I did not make a scene. I made a choice. And when the world suggested there wasn’t room for her, I built a chair and a table and a room that fits the life we’re living.

If that feels like a happy ending, it’s because it is. Not the fireworks kind. The kind where a girl who once slept on a couch in her “going-to-Grandma’s” sweater now sleeps before a lab day in a life she chose. The kind where a mother who was once the “weird one” for wanting to understand how the body works gets to watch her daughter design devices that give bodies more time to work. The kind where the people who hurt you learn—slowly, imperfectly—that consequence is not cruelty and repair is not owed but possible.

On the fourth of July that year, we grilled in the backyard with neighbors and the ER nurse’s toddlers tried to catch fireflies in jars that never closed tight. A small flag leaned in a planter. Abby lit a sparkler and drew a circle in the air and said, “Look. Room.”

Yes. Room.

And when the first firework cracked the sky, we didn’t flinch. We looked up. We let the color take the dark and remake it into something worth standing under.

News

My son demanded that I cover his wife’s $300,000 debt, saying I needed to transfer the money by tomorrow and stressing “no delays,” but I simply nodded calmly and started packing my suitcase; a few hours later, I was on a plane, leaving behind the house that had once been in my name. When he came back to my place looking for the money, all he found was a locked door and an envelope that left him stunned.

I needed the money yesterday, my son demanded, handing me his wife’s $300,000 debt as if it were a simple…

While I was quietly on vacation in Colorado, my daughter sold the penthouse in my name to plug her husband’s money problems, laughed that I’d have nowhere to live now, and never once suspected that the “little place” they rushed to sell was actually the least important property in the quiet, carefully planned portfolio I’d been building for years.

You know, they say you never really know someone until they show you who they truly are. I learned that…

After my ex-husband told me to leave his house with nothing after the divorce, I pulled out an old bank card my late father had left behind and tried to use it at a small U.S. branch, and the way the tellers suddenly rushed to call their manager, whispering, “Look at the account holder’s name,” exposed a family secret I was never meant to find out.

My husband put me out and kept all my assets just to hand them over to his mistress. All I…

My Twin Sister Showed Up at My Door in a Small American Town Looking Drained and Hiding Behind Long Sleeves, and When I Realized Her Husband’s Behavior Was Quietly Breaking Her Spirit, We Swapped Places So I Could Smile, Take Notes, Work With a Lawyer, and Turn His Picture-Perfect Marriage Into the Wake-Up Call He Never Saw Coming.

My twin sister came to visit me at the hospital, covered in bruises all over her body. Realizing she was…

I went bankrupt and my husband decided to leave, and at 53 I went to a plasma donation center just to receive $40 to get by, but after seeing the results the nurse called in a doctor and said I had the extremely rare RH-Null blood type that only a few dozen people in the world have, which opened the door to an unexpected financial support offer from a billionaire family in Switzerland.

The receptionist handed me a clipboard with a stack of forms attached to it. Her practiced smile never reached her…

At 2:47 a.m., my grandson called me from the police station, sobbing that his father believed every word his stepmother said accusing him of causing her to fall, yet when I walked in the duty officer suddenly stood rigid, his face draining of color as he whispered, “I’m sorry, I didn’t recognize you,” and from that moment our family was dragged into a confrontation with the truth.

My grandson called me late in the night. “Grandma, I’m at the police station. My stepmother hit me, but she’s…

End of content

No more pages to load